Decreasing safe spaces for human

rights defenders in Negros.

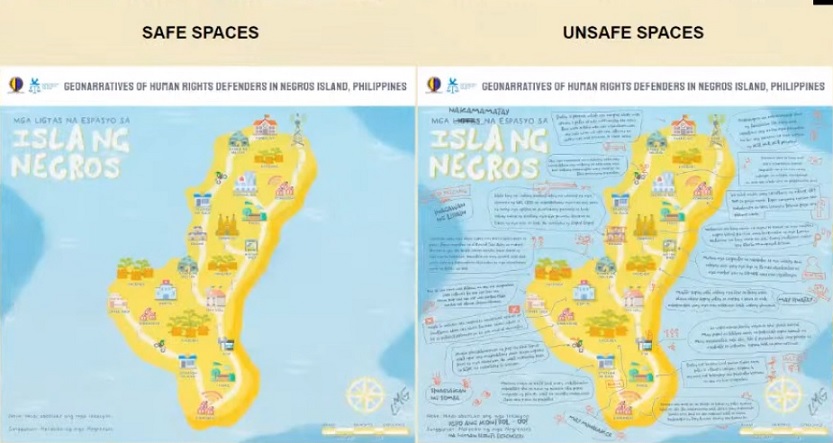

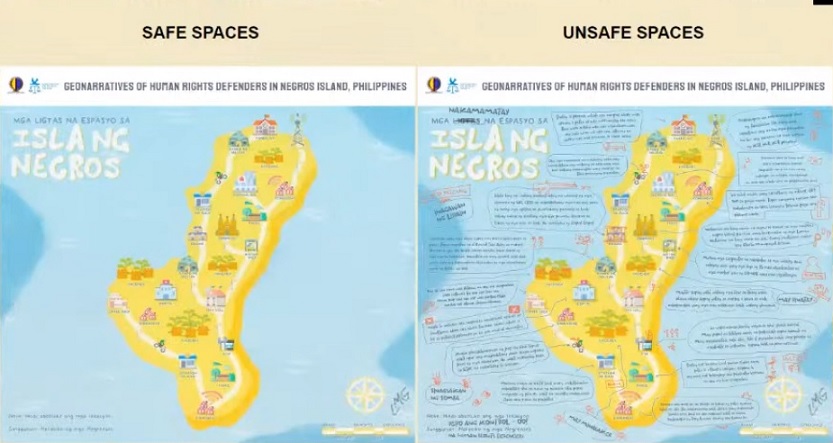

The spaces in which human rights defenders feel safe are getting smaller as government agents intensify their counter-insurgency attacks, a study by geographers from the University of the Philippines has shown.

In view of the findings, the five-person research team recommended, among others, the legislation of an anti-extrajudicial killing (EJK) measure to protect HRDs from various forms of violence and harassment.

The group also proposes the abolition of the National Task Force to End Local Communist Armed Conflict (NTF-ELCAC), which has been taken to task for red-tagging and other forms of harassment and violence against HRDs, resulting in reduced safe spaces. The agency’s budget can be used better if reallocated to COVID-19 aid, the researchers said.

The study, titled “Geo-narratives of Human Rights Defenders in Negros Island, Philippines,” was born out of a passion for social justice and human rights, according to Leonardo Miguel Garcia, one of the researchers.

It was intended to increase public awareness about the plight of HRDs in the country’s fourth largest island, which has become known as the “hotbed of HRD deaths and violence.”

HRDs are defined in the study as “people who work to protect and promote not just individual human rights, but more importantly, collective rights of the toiling masses,” with bias toward the most oppressed and exploited.

Garcia said HRDs themselves came up with the meaning, which is an expansion of the 1998 United Nations General Assembly’s definition as any person or group who use non-violent avenues to promote, preserve or fight for the protection and implementation of basic human rights.

Perception of unsafe spaces

According to the UP study, the violence experienced by HRDs limited the safe spaces where they can thrive as they had to bear with harassment and intimidation in public, private and even in virtual spaces.

“Sa violence, overall na EJKs na nangyayari sa island ay nakaapekto rin sa pagtingin ng mga HRDs sa espasyong ginagalawan nila,” said Bernardino Dela Cruz Jr., another researcher.

(In terms of violence, EJKs on the island affect how HRDs perceive the space they operate in.)

“Participants indicated the existence of dark and narrow alleys in their daily routes cause a certain level of anxiety for them,” added Yany Lopez, the project’s head researcher.

She noted that HRDs also feared well lighted and crowded spaces such as major highways, transport terminals and jeepney stops.

“Ang bahay, ang grocery, mall. Sa kalakhan ng tao itong mga lugar na ito spaces of leisure, spaces of safety pero para sa ating mga HRDs maski yung waiting shed, maski ang daan ay hindi ligtas,” Mylene De Guzman, another member of the research team, said.

(Houses, grocery, and malls. These were considered spaces of leisure and safety for almost everyone, but for HRDs, even waiting sheds and roads cannot be considered safe spaces for them.)

Apart from places, HRDs also attributed their perception of risk and safety to time.

“Some of the participants felt the need to go home very early from their school or work as they perceived that wandering around during the night could pose a danger to them,” Lopez said.

‘Place matters’

Arnisson Andre C. Ortega, another researcher who joined the virtual forum from Syracuse University’s Department of Geography and the Environment in New York, said the study used geonarratives to emphasize that “place matters” in the struggle for human rights in order to “unpack and understand the unseen narratives” of HRDs in Negros Island.

The researchers came up with a mapping scheme to tell stories of abuses, harassment and violence that HRDs experience both physically and online.

“Unlike traditional maps that account only for certain structures, political boundaries and macro-level space,” he explained, the project conducted a “counter-mapping” that accounts for “often hidden everyday geographies” in which various forms of violence are committed against HRDs.

In recent years, international human rights groups have considered the Philippines as one of the deadliest countries for HRDs based on reported incidents of arbitrary arrests, extrajudicial executions and various forms of harassments and threats.

The researchers presented the study, a project funded by the Commission on Human Rights, in an online forum on Friday, July 9, under the auspices of the UP Department of Geography.

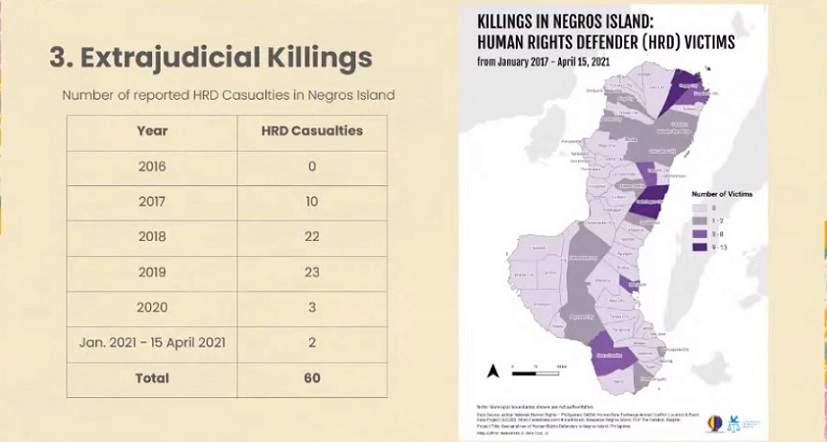

The study was focused on Negros Island, where more than 90 HRDs, lawyers, farmers, teachers, and church workers have been killed since 2017.

HRDs alone account for at least 60 deaths on the island since President Rodrigo Duterte took office in July 2016, based on the tally of human rights group Karapatan. The number accounts for nearly half of the 134 recorded HRD deaths across the country under the Duterte administration.

Such a number is unprecedented, according to Clarizza Singson, secretary-general of human rights organization Karapatan-Negros Island.

“For five years under Duterte at hanggang sa pahuling taon na ng kaniyang termino bilang presidente, ang Karapatan sa Isla ng Negros ay nagtala at nag document ng highest numbers of cases of human rights violations” said Singson, a reactor in the study’s virtual presentation.

(For five years under Duterte and up to the last year of his term as president, Karapatan – Negros Island has recorded and documented the highest numbers of cases of human rights violations.)

Recently, the Philippines ranked last among 134 countries in Global Finance’s list of safest countries in the world. Previous reports from the Armed Conflict Location and Event Data Project, International Federation of Journalists and Global Witness have shown that the Philippines is a dangerous country for civilians, journalists, and activists alike.

State aggression in Negros

The study further revealed that the state mediates violence as they employ physical offensives against HRDs in both public and private places.

“Ang mga state forces … higit pang nagka-license na pumatay kahit na ito ay nakabatay kahit sa simpleng suspicions o subscription sa communism,” said Garcia in presenting the various forms of dehumanizing treatment to HRDs.

(The state forces … had the license to kill even if it was grounded on mere suspicion or subscription to communism.)

In Nov. 2018, Duterte issued Memorandum Order No. 32 which deployed additional forces of the AFP (Armed Forces of the Philippines) and PNP (Philippine National Police) to Negros Oriental and Negros Occidental, following the spate of killings in the area.

Singson said this was the same year when Negros was placed under a state of emergency. According to her, the memorandum order and the blow of NTF-ELCAC to end local communists’ armed conflict resulted in intensified military operations within the region, especially with the community of farmers.

The intensified counter-insurgency operations in Negros further made spaces unsafe and potentially dangerous for HRDs.

The researchers cited a report of Karapatan that 92 political prisoners are detained in Negros. Most of them had been served search warrants that did not mention the exact location of the place to be searched.

The study also noted the government’s efforts to criminalize dissent that have developed stigma and distrust among HRDs.

A report by Investigate PH released last March showed that the armed forces are now bolder in killing dissenters as the police are now executing HRDs similar to that of extrajudicial killings.

Lopez said the study’s participants expressed general mistrust for the police and army and that their mere presence even in public spaces has been a cause of concern and anxiety among HRDs.

The UP study likewise found out that the government’s inaction in resolving the deaths of HRDs only maintains the status quo.

“Ang pagpapanatili ng unjust working condition sa Negros ay isa ring porma ng violence at iyong kawalan o kakulangan ng aksyon sa pagtugon ng gobyerno sa mga kinakaharap na problem ng HRDs ay isa ring problema,” said Dela Cruz.

(Maintaining the unjust working condition in Negros is another form of violence and government inaction to resolve issues faced by HRDs is also part of the problem.)

To address this, the study recommended establishing grievance procedures.

“Paano kung ang perpetrator ay ang pulis o ang army? Kanino lalapit yung mga HRDs?” Lopez asked, to justify the reason behind the proposal.

(What will we do if the perpetrator is the police or army? Who do HRDs go to?)

Apart from the abolition of the NTF-ELCAC, Lopez said the group suggest improving the lines of communication between HRDs and local CHR where the major concerns of HRDs are adequately addressed.

Distorted and biased information

As HRDs face dangerous conditions in physical and online spaces, media further limit safe spaces for HRDs. The study revealed that various media platforms misrepresented HRDs, ascribing to them terrorist identities based on mere assumptions and suspicions.

“Ilang mga news outlets din yung patuloy na iresponsable nagdi-disemminate ng distorted and biased information hinggil sa mga HRDs. Kalimitang makikita ito sa mga inaresto at pinatay na mga aktibista na nabbrand lagi, constantly, na mga NPA leaders,” Garcia said.

(Some news outlets continue to disseminate distorted and biased information against HRDs irresponsibly. This can often be seen on arrested and killed activists who were branded as NPA leaders.)

“Mistulang mga echo chamber lang din yung ilang mga news reports na mga statement sa mga militar na kung hindi nag redtag ay nagdya-justify ng kanilang mga operations,” Garcia added.

(The news reports seemed to be an echo chamber where statements justify military operations, if not red-tagging.)

To amplify public awareness about the situation, Lopez said that one way to achieve increased awareness is to expand and strengthen media coverage about the situation of HRDs in Negros.

Jean Loreile Raoet is a student of the University of the Philippines writing for VERA Files as part of her internship.