By ANTONIO JOSE GALAURAN and LUIS ADRIAN HIDALGO

(First of two parts)

IN the midst of the concrete jungle that Metro Manila has become, a forest continues to thrive.

But the 22-hectare University of the Philippines Arboretum is in peril, owing to the inroads of urbanization and influx of informal settlers in the last five decades.

A plan to save the arboretum, by turning it into a National Botanical Garden, has raised questions of what is to become of some 2,500 informal settlers that call the metropolis’ last standing forest home.

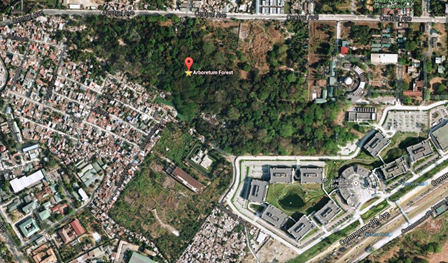

The manmade forest located behind the UP-Ayala Technohub along Commonwealth Avenue in Quezon City was initially an open land donated by the Tuazons in 1939 as an extension of the university’s first campus in Manila. It had served as a forest nursery of the now defunct Department of Agriculture and Natural Resources Reforestation Administration before its care was officially transferred to the University of the Philippines-Diliman (UPD) in 1962. The repository of endangered, endemic and exotic plant species has evolved into the lush forest that the arboretum is today.

In a bid to conserve and preserve the UP Arboretum, the university on Feb. 12, 2013 entered into an agreement with the Department of Agriculture, Department of Environment and Natural Resources, and the UP Beta Sigma Fraternity to develop it into the National Botanical Garden under a 10-year master plan.

Using high-precision instruments, the DENR has already geotagged 422 trees, some towering as much as 20 feet or more, and encoded their specific data. Two-thirds of the trees were found to be in good to very good condition, 24 percent in fair condition, and 1 percent in poor or in critical state.

The mature trees are mostly kupang (46 percent), mahogany (11 percent), narra (also 11 percent) and rain tree (7 percent). But save for the narra trees, which are endemic to the place and can live for centuries, most of the tree species within the Arboretum are short-lived and exotic.

The DENR also reported thick litter on the forest ground and the presence of wildlife such as birds. They include the long-tailed shrike, olive-backed sunbird, Philippine pygmy woodpecker, brown shrike, yellow-vented bulbul, lowland white-eye and pied triller.

A land survey by the DA confirms the diverse flora and fauna at the arboretum, as well as a hectare of grassland and a manmade pond.

The DA also concurred with the DENR’s finding that the arboretum’s soil is still in a fairly good condition. It said the area may be further developed for farming as long as the soil is first rejuvenated.

But experts from the DENR and DA also observed that encroachment by informal settlers appears to have comprised the health of the arboretum.

Informal settlers at present occupy nearly eight of the 22 hectares of the UP Arboretum, including over and near existing waterways, a sharp contrast to what the forest was like 50 years ago.

It was barely inhabited then. Only gardeners and caretakers, all of them UP employees, were allowed by the university to set up homes there. In all, seven structures stood in the forest.

“If you were not an employee of UP, you were not allowed (to live in the forest),” said Romeo Margallo, 59, one of the original settlers who remains a gardener of the university to this day.

“There were only a few of us here before. We were like ghosts. You didn’t easily see people because of the thickness of the forest,” said Leocadio Alasaas, 72, another original settler and a former gardener of UP.

The first settlers were permitted to live at the arboretum on condition that they would voluntarily vacate it when the UP needed it. They were not supposed to let anyone else in.

But the agreement was breached and soon their extended families and friends moved in. Some residents also began renting out their house to newcomers.

Antonino Basconcillo, president of the local organization Samahan ng Mamamayan ng Pook Arboretum and a settler since 1969, said informal settlers from other parts of Metro Manila, including Tondo in Manila and in Caloocan, Navotas and Malabon cities, gradually made their way to the forest.

Land syndicates took advantage of informal settlers. An alleged lawyer, known only as “Minor,” sold them parcels of arboretum land for as much as P50,000 that supposedly came with titles, Alasaas said.

When the 1960s drew to a close, 17 houses had been put up at the arboretum, according to data from UP’s Office of Community Relations. The number rose to 30 in the 1970s, 98 in the 1980s and 171 in the 1990s. Today, a total of 597 households or 2,536 individuals live there.

A containment policy implemented by the university failed to stop people from sneaking into the arboretum and building homes.

The DENR study shows that many of the trees in the arboretum are shallow rooted, the roots not deep enough into the ground, making them less stable and more prone to falling over.

Although shallow rooting can be a natural characteristic of some tree species’ morphology, DENR arborist Saturnino Danganan Jr. said it can also be caused by human activities such as excessive sweeping of soil.

DA agriculturist Roger Creencia backs Danganan’s observation, adding that shallow-rooted trees pose a threat to the safety of arboretum inhabitants.

Reports of logging by informal settlers have also reached the DENR and DA. Trees are reportedly being cut down for firewood or construction materials.

Engineer Bony De la Cruz of DA’s Bureau of Soils and Water Management recalls seeing some residents harvesting wood during their survey. Although this turned out to be litter or dry branches that fell to the ground upon closer inspection, he said, “Pero hindi natin alam, ‘di ba (But we don’t really know, do we)?”

Jose Manguera, chief of DA’s Soil Conservation Management Division, raised the possibility that harvesters temporarily leave the wood after cutting to let it dry and then return to collect it later on to avoid getting caught.

Obstruction of natural waterways in the forest has become a problem at the UP Arboretum. Encroachment of informal settlers on the waterways itself and in places near them hinders the flow of existing and accumulated water in the area and results in occasional flooding that may be a threat to the inhabitants’ safety.

The presence of a junkshop in the arboretum has, meanwhile, contributed to soil pollution. According to Danganan, improper disposal of chemicals coming from different materials brought to the junkshop will percolate into the ground and affect soil quality, as well as the ground water.

“Of course we all know that all the chemicals coming from the dismantled materials (at the junkshop) can possibly ruin the quality of the soil,” he said. “The small creek there may eventually (also) be ruined.”

This, in turn, may affect the growth of the trees and the wildlife in the forest. “Birds and small critters are very sensitive to (polluted) water,” Danganan said.

Free-roaming goats in the forest have also been identified as another threat. Left unmonitored by their owners, Danganan said they may consume small plants which may turn out to be new plant species.

(To be concluded)

(This report is based on the authors’ undergraduate thesis done last year for their journalism degree at the University of the Philippines-Diliman under the supervision of VERA Files trustee Yvonne T. Chua. The thesis placed second in the 2014 Philippine Journalism Research Conference.)