The Philippines has a wealth of beautiful stories and wonderful imagery that children can appreciate. On this anthropologist-poet Padmapani L. Perez and literary scholar Sacha Garah are agreed. The two spoke at the recent Philippine Board on Books for Young People’s second book summit at theGT-Toyota Asian Center Auditorium, University of the Philippines campus in Diliman, Quezon City.

Here are their observations about children’s books being produced in Baguio City and the Cordillera Autonomous Region:

- These stories are collected or validated through networks of kin, friends, fieldwork, interviews or workshops;

- They are written or retold and illustrated by writers and artists from the Cordillera or with some connection to the Cordillera;

- They are multilingual;

- They are published by non-government organizations, foundations, universities or government agencies;

- The collaboration happens in the processes of research, creation, validation and translation;

- The books are distributed in schools and libraries, usually at no cost to the community;

- The books are bankrolled by communities’ overseas Filipino workers, local politicians and civil society;

- They are not always commercially available; and

- Some are now out of print.

Perez said. “Children in the Cordillera and in other regions deserve stories in which local cultures are living things, not just things or tales of the past. They ought to have books in which they can recognize themselves.”

Garah said, “The works we are creating should reflect the kind of readership we want to foster in today’s generation, those who we hope will one day become guardians, bearers and lovers of our culture.”

Padmapani L. Perez, anthropologist and poet

Asked what got her keen on children’s literature, Garah answered, “Partly because I wanted to do research that is closer to home for my M.A thesis and partly because I’m a nanay. The books I get my hands on most of the time are books that I read to my daughter. I’ve hoarded so many, mostly Western, because they’re everywhere. When Adarna Books went on sale sometime last year, I bought a lot of storybooks. I was thrilled to be reading to my child Philippine children’s stories, but I was hoping to find Cordillera stories.”

She continues, “Doing a preliminary survey of children’s books on the Cordillera was a way for me to get started with writing my thesis. Having little time to read other books I thought I’d work with the books I have now. The earliest book I have was published in 1990, Cordillera Tales by Maria Luisa Aguilar Cariño. Perhaps this was the first illustrated collection of folk tales. Since 2000, there has been an increase in the production of children’s books by NGOs, government institutions, mainstream publishers and individuals who opted to self-publish. Based on the survey I did, 45 books in nearly three decades (1990-2016) isn’t much. But works in progress prove promising.”

Perez, co-owner of Mt. Cloud Bookshop in Baguio, traced her interest to the time she and her sister Feliz opened the store. “We wanted to have a good collection of titles from the region. Until now, our selection of Cordillera children’s books is quite thin. Bernadette Neri, author of May Ikaklit sa Aming Hardin, gave a talk in the shop. I was struck by what she said: in Philippine children’s literature, there are few books that are about children who are NOT middle class, living in cities, Christian, with hetero-normative families.”

She added, “In a summer writing workshop for adolescents, it bothered my co-facilitators and I that the characters our participants made up were blonde, blue-eyed and living in countries where there was winter. These encounters intensified my interest not just in Cordillera children’s literature but in diversity in Philippine children’s lit. Where were our own stories in the mountains? Stories about the realities we know and live?”

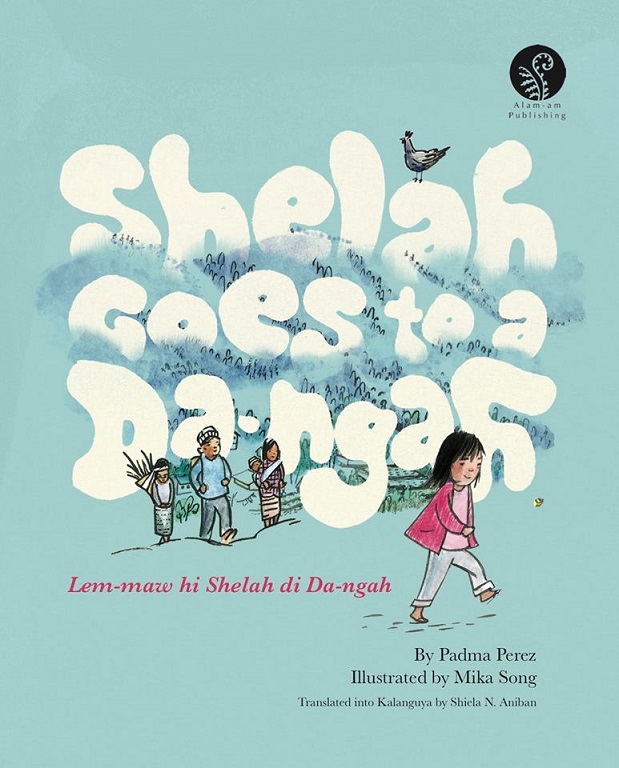

As to why the titles quickly go out of print, including Perez’s Shelah Goes to a Da-ngah, Garah explained, “Most of these are project-based and are not for sale. When the target number of copies have been made and distributed to schools and libraries in the communities, the production ends. Some books which are out of print are available to view and download online for free.”

Perez said, “In my case, I created Shelah Goes to a Da-ngah because I wanted to give something back to the community of Tawangan, Benguet. I did my fieldwork there from 2004 to 2005. It took me more than ten years to figure out what I could give the community in return for accepting my presence! I asked myself, ‘What can I do for them?’ Then the question turned into ‘What is it that I can do?’ I can write. So I wrote a children’s story. I wanted to give them something unique that would be part of their future.”

Sacha Garah

This is how she went about publishing and creatively distributing the book. “I used my own savings. A cousin who believed in what I was doing made an investment. I didn’t think people outside of Tawangan would be interested in the story, but I needed to raise more funds so I could recoup some expenses and print enough books to give every family in Tawangan their own copy. So I decided to try the buy-one, give-one model that other companies have used (for shoes, school bags, jeans, and so on). I came up with a scheme in which you could pay for two and send one to Tawangan, or you could buy 10 for Tawangan and get one free. Friends and family were incredibly supportive. Social media was a huge help. It didn’t take long before I had 200-plus copies earmarked for Tawangan. We delivered the books on January 1, 2016. An NGO working in other Kalanguya barangays in Benguet got wind of the book through friends and social media, and bought 200 more copies for distribution in those communities. I wasn’t expecting the demand so I had to do a print run especially for them.”

Most stories set in the Cordillera cover these subjects, according to Garah’s study:

retellings from folklore, environmental problems, stories of resistance (martial law years). contemporary stories that portray childhood experiences (e.g., going to a new school, wanting to make a dream come true, participation or non-participation in a ritual or a tradition).

At the PBBY summit she learned that “children’s writing from or of the regions is vibrant, especially in Western Visayas. Yet some issues of production need to be addressed: availability of these books in and for the market, availability of these books in languages other than the language of origin and the need for more original and contemporary stories.”

Perez cited MJ Tumamac and Noel de Leon, who spoke about children’s books in Mindanao and the Visayas. “It’s inspiring how they organize story-telling sessions, workshops and even children’s book clubs. Tumamac raised something important when he shared his observation that in the production of books, indigenous communities are treated first as the source of stories, then as recipients of the books. They are rarely involved in the creative process. This has to change. Close collaboration may be the key. The more people work to create book diversity for Filipino kids, the better. It would be great to have some cross-cultural, literary exchange between the regions, and we talked about the possibilities!”#