By PABLO TARIMAN

WITH a generation that goes wild over Justin Bieber, Charice Pempengco, Bamboo, River Maya and Parokya ni Edgar, how can the rondalla survive and prevail in the Philippine music scene?

WITH a generation that goes wild over Justin Bieber, Charice Pempengco, Bamboo, River Maya and Parokya ni Edgar, how can the rondalla survive and prevail in the Philippine music scene?

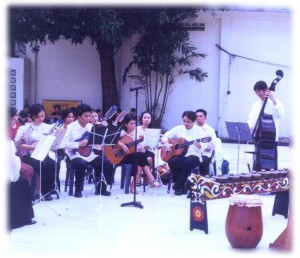

The rondalla is an ensemble of stringed instruments made of native wood and played with a tortoise shell plectrum. This ensemble only surfaces during school convocations, Filipino week and is occasionally seen at the Ninoy Aquino International Airport (NAIA) immigration lobby welcoming balikbayans as part of a tourism come-on.

It also resurfaces in some editions of the National Music Competitions for Young Artists (NAMCYA) in the category of Filipino ensembles where it gets token exposures at the Cultural Center of the Philippines (CCP).

If the rondalla makes an appearance in popular noontime shows, young people will most likely describe it as “cool.” For those unaware of its origins, it could get sneers like the popular condescending, “E-e-e-e-w-w-w!”

The great plucked tradition will have another chance at revival with the staging of the Third International Rondalla Festival billed as “Cuerdas sa Pagkakaysa” (Strings of Unity) from Feb. 12 -19 at the City of Palm Trees, Tagum City. This festival will see a gathering of over 500 artists, representing some of the best rondalla groups from all over the country and highly select foreign experts in plucked string music.

At the helm of this rondalla festival is composer Ramon Santos, who is head of the Musicological Society of the Philippines. Santos, who was bypassed for the National Artist for Music award by former president Gloria Arroyo in favor of massacre king Carlo Caparas, said the festival is intended to activate and provide the initial energy to the World Rondalla Society as a global organization.

At the helm of this rondalla festival is composer Ramon Santos, who is head of the Musicological Society of the Philippines. Santos, who was bypassed for the National Artist for Music award by former president Gloria Arroyo in favor of massacre king Carlo Caparas, said the festival is intended to activate and provide the initial energy to the World Rondalla Society as a global organization.

“We certainly hope that this festival will not only sustain the development of an important musical patrimony but more importantly will also promote global peace and understanding through a shared music tradition,” Santos said during a pre-festival briefing in Tagum City.

The rondalla was introduced in the Philippines by the Spaniards who first came to the islands in 1521. Rondalla comes from the Spanish word “ronda”, which means serenade. Consisting of various plucked string instruments of the lute and guitar family (banduria, laud, octavina, gitara and bajo), the Philippine rondalla is also deeply associated with other classical and folk instrumental traditions the world over — from the pipa, shamisen and gambus of Asia, to the cuatro and charanggo of the Americas as well as the myriad incarnations of the lute and the mandolin of Europe and the Arab World.

The first attempt to revive the rondalla was during the first International Rondalla Festival held in the Bicol region in 2004, followed by the second International Rondalla Festival in Dumaguete City in 2007. It saw a week-long gathering of plucked string masters from Europe, Asia, the Arab region, Australia and the Philippines.

Santos, who is initiating a rondalla revival for the third time, earned his doctorate degrees from Indiana University and State University of New York but he didn’t specialize in the likes of American composers Samuel Barber and George Gershwin.

Instead, he explored the aesthetic frameworks of Philippine and Southeast Asian artistic traditions to come up with versatile uses of the country’s indigenous instruments. Although he respects the country’s Western musical heritage, he spent a lifetime in field studies of Philippine traditional music such as the musical repertoires of the Ibaloi, the Mansaka, Bontoc, Yakan and Boholano.

While many of his countrymen were preoccupied with pop music and a small but influential sector propagated Western classical music, Santos zeroed in on Philippine contemporary music and became a distinguished though relatively unheralded composer.

His work “Dw’gey” was premiered at the Biennale of Contemporary Music in Israel in November 2006 and again performed at the Asia-Pacific Week Festival in Berlin in September 2007. His work “S’geypo” for 16 flutes was performed by the French Flute Orchestra in Paris in September 2008.

On the significance of the Filipino rondalla, Santos said it represents a national heritage that is locally unique yet globally connected. He added that it is a tradition that evolved from the Spanish comparza, group of musicians who played on stage, and estudiantina, a group of university musicians in Spain who also use instruments used by present-day rondalla players.

“The rondalla has been adopted, modified and developed by the Filipino to express a national folk life and social environment,” Santos shared. “Since the late 18th century, it has enriched the musical life of Filipinos of all ages. Its repertoire has grown from folk songs, dances and short pieces to full-blown classical and modern compositions and adaptations.”