Riena Mercene is weeks away from graduation. On June 25, the 22-year-old will bid farewell to the University of the Philippines College of Education where she just finished a bachelor’s degree in secondary education.

Mercene, who is preparing to take the Licensure Examinations for Teachers this September, has always dreamt of being a teacher. “It’s a calling, I guess. Since I grew up with a mom as a teacher, teaching also grows (on me),” she says.

Teaching is a profession that requires passion, like what Mercene and her mother have, and love for country, experts from the UP College of Education say.

They also say the wide range of jobs, the job security that accompanies many of these, and the better pay for government teachers in recent years have made teaching an attractive profession again.

On his last stretch next semester, education senior Bruno Abenojar is confident he will land a job soon—in or outside a classroom. He says his degree has prepared him for other jobs such as human resources.

Among Mercene’s job options are teaching in the Alternative Learning System or going into research in a post-graduate course.

Says Abenojar: “Marami kasi talagang job opportunities. Di ka lang limitado sa classroom setup (There are many job opportunities for education graduates. You’re not just limited to the classroom setup).”

More students, more graduates

The numbers are proof that teaching has made a comeback.

In the last dozen years, enrollment in the education and teacher training track at all levels of tertiary education has climbed from being the third to the second most popular courses among the 21 discipline groups classified by the Commission on Higher Education (CHEd).

Teacher education is among the commission’s list of priority disciplines.

The number of education enrollees rose from 366,988 in schoolyear 2004-2005 to 791,284 in schoolyear 2015-2016, or by an average of 7.6 percent every year, according to CHEd data. From schoolyear 2010-2011 to 2015-2016, the average annual increase in enrollment was higher, at 11 percent.

The number of education graduates grew correspondingly over the five-year period. A total 62,715 finished teacher education courses in schoolyear 2010-2011; by schoolyear 2015-2016, education programs graduated 116,305 students.

“Sa lahat ng education, may bahagi ang (pagtuturo). Kung hindi lahat ng propesyon ay mayroon ding nagtuturo (Teaching forms part of all kinds of learning. If not, all professions require educators),” UP education professor Virgilio Manzano says, explaining the versatility of graduates of teacher education.

Manzano, who helped craft the Makabayan (Nationalism) curriculum for the Department of Education in 2002, says he believes one’s love for country has renewed students’ interest in education.

Shiela Marie Atanacio, a secondary education graduate of Philippine Normal University, says she and her schoolmates also learned how important it is to love the profession.

“Sa PNU kasi, doon na kami hinubog. Binigyan kami ng mindset na ‘magtuturo ka,’ kaya hindi ko siguro makita yung sarili ko na mag e-excel sa ibang trabaho aside (from) teaching (In PNU we were given the mindset that we are going to teach, which is probably why I cannot see myself excelling in any other job than teaching),” she says.

Atanacio, who only started teaching last year in Pasay City West High School, has come to appreciate the role of teachers as children’s second parents.

“Dito sa private (school), busy yung mga magulang. May tendency na mag open up sila sa mga teachers nila (The parents of students in private schools are usually busy. There’s a tendency for the children to open up to their teachers),” she says.

Fewest graduates from Mindanao

Data show Metro Manila, Central Luzon and Western Visayas are the top three regions that turned out the graduates, and provinces in Mindanao the fewest.

For Vanessa Oyzon, who taught for 13 years in the UP Integrated School before she became an education professor at UP in 2006, it boils down to cultural nuances and safety concerns.

“People (in Mindanao) do not give high premium to education,” Oyzon says. “Sa Visayas, mataaas ang pagtingin ng mga tao sa teacher. Sa North Luzon, yung mga teacher highly revered (Especially in Visayas, they look up to teaching. In North Luzon, teachers are highly revered).”

She says threats posed by bandit and rebel groups to Mindanaoan communities, including teachers, also pose a problem. UP education professor Romylyn Metila agrees, saying “safety risks” keep the children from completing whole-day shifts.

Like many other college students, education students prefer to study in the city.

“(May notion na) ‘pag nag-aral ka sa city, Manila or Cebu City or Baguio or Davao, mas prestigious. Mas sosyal (There’s a notion that if you study in the city, in Manila or Cebu or Baguio or Davao, it’s more prestigious. Fancier),” says UP education professor Maria Mercedes Arzadon.

Still more female teachers

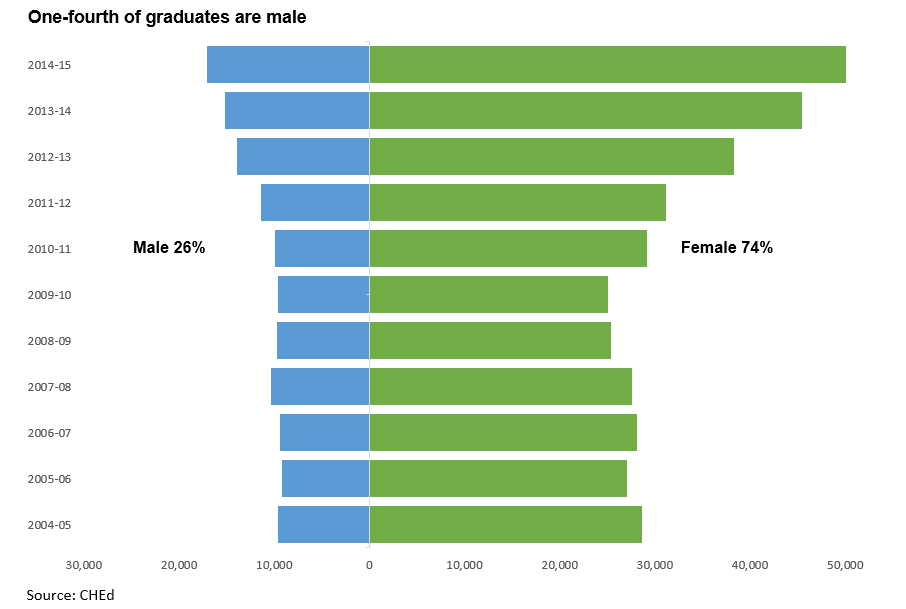

Of the educators nationwide, twice as many male educators have graduated over 11 years. A total of 9,564 male education students graduated in 2004. Ten years later, the figure rose to 15,187.

Yet they are still far outnumbered by women: Only one in four teachers is male.

This comes as little surprise to experts like Arzadon. The profession, after all, has long been “feminized” such that any male who entertain thoughts of becoming a teacher is branded as weak or dull, she says.

This, of course, wasn’t always the case. During the American regime, the teachers in the country were at first mostly men.

But the Americans soon realized hiring women was cheaper. The women, who would traditionally work as housewives, did not demand a high pay, Arzadon says.

Metila says literacy rate also affects career choices. Data from a 2013 report of the Philippine Statistics Authority shows women have higher literacy rates than men, with 92 percent of females functionally literate, or can at least read, write, compute and/or comprehend, versus 89 percent of males.

Metila suggests how culture influences boys. “‘Pag ang nakikita niya laging nagbabasa ay babae, nagbibigay yun ng isang idea sa kanya na in a very subconscious way so parang hindi panlalaking gawain ang magbasa (If a boy sees a girl reading, it would give him the idea that reading is not a thing for boys).”

Oyzon says men who start out teaching will eventually leave the profession for practical reasons.

“‘Pag ikaw breadwinner, syempre gusto mo ng ibang paraan (If you’re the breadwinner, you’d look for other ways),” she says.

Better pay

But more Filipinos are taking up education because salaries of public school teachers have remarkably improved, Arzadon says.

The Congressional Commission on Education to Review and Assess Philippine Education (EDCOM) Report of 1991 has played a significant role in increasing teachers’ basic salaries, she says. The report traced the decline of the quality of public education in the Philippines to, among others, a lack of government investment in education.

Over the years, salaries of civil servants have increased, including those for public school teachers. In early 2015, then President Benigno Aquino III signed an executive order mandating the salary increase of civil government employees, effective Jan. 1, 2016 up to 2019.

The monthly basic pay of newly hired public school teachers is now P18,217. Public school teachers are also entitled to a midyear bonus or 14th month pay.

The teachers’ basic pay will be adjusted to P19,233 by 2019 under Aquino’s executive order, which sought to close the gap between salaries of employees in the public sector and private sector.

While the pay may be better in public schools, teaching in private schools has a few advantages.

Says Tricia Ann Artienda, 24, who taught Technology and Livelihood Education in a private school in 2015: “Nung nag-start ako last year, sobrang nag-struggle lang ako sa pag-kita ng pera. So dapat talaga mag qui-quit na ako this year (I struggled last year when I was starting because of the pay, so I was planning to quit this year).”

She thought of transferring to a public school where the salary is better, but stayed in the private school in the end.

Artienda taught in Ramon Magsaysay High School, a public school in Cubao, Quezon City for six months as requirement for her business education degree at the Polytechnic University of the Philippines.

The teaching load was different. Teachers are mostly required to only handle one grade level in public schools due to the volume of students. There are public schools that have two or three shifts in a day, which is problematic for a skills-based course like TLE, Artienda says.

Arzadon says, however, the flexible time, on top of the salary, also entices education graduates to apply at public schools.

Republic Act no. 4670 or the Magna Carta for Public School Teachers limits the actual classroom teaching of public school teachers to six hours at most “except when undertaking academic activities that require presence outside the school premises.”

Despite many problems in public schools like the lack of facilities, crowded rooms and short class hours, Artienda says many of her contemporaries are more inclined to teach in public schools.

Education as an advocacy

Artienda says she hopes younger generations will continue to choose teaching as a career—and a lot depends on the teachers they have now.

“‘Yong mga bata, may possibility pa, kasi kapag nakikita nila na magaling ‘yung teacher nila, na inspiring ‘yong teacher nila, i-iidolize nila ‘yon. Gugustuhin din nila maging kagaya no’n (If they see that their teachers are competent, that their teachers are inspiring, they will idolize them.

They would want to be like them),” she says.

It was the opposite for Abenojar. “Unfair and unreasonable” teachers in high school were what drove him to pursue education in college. He wanted to make a difference.

“I want to be a nice, cool teacher,” he quips.

But for Oyzon, education is an advocacy.

In the late 1980’s, she recalled how she and her fellow education majors were embarrassed by a professor in one of her general education courses at UP, where they were in a class with economics students.

On their first day, the professor divided the class into two, based on their degree programs and told the education majors: “‘Mga educ, second-class citizens kayo kasi ang bobo niyo (You education majors are second-class citizens because you are ignorant).’”

That was a defining moment for her batch, Oyzon says. She and other education majors made a vow: “We should not let this happen.”

This was “a time when teaching was frowned upon,” she says. But things have since changed.

“I tell the college of education students, not even your co-students (can) tell you na titser ka lang (you’re just a teacher),” Oyzon says. “Kasi kung ganon ang pananaw natin, paano mo iaangat ang kalidad ng pagtuturo (Because if that’s how we view ourselves, how can we raise the quality of teaching)?”

(The authors are journalism majors at the University of the Philippines-Diliman. They submitted this story for their Computer-Assisted Reporting (J116) class taught by journalism professor Yvonne T. Chua.)