Experienced teachers teaching newbie and just as skilled teachers—this was the scene at the recent “For Love of the Word: Workshop on Teaching Philippine Literature in High School and College” at the Sarmiento Hall of the University of the Philippines Baguio.

A project of the Philippine Center of International PEN (Poets, Playwrights, Essayists and Novelists) Civil Society Program, the workshop featured De La Salle University literature Prof. Shirley Lua expounding on survival tips in the classroom. She narrowed them down to three:

- Teach a few good poems, but teach them very well.

- Do not cover everything. Focus, focus, focus.

- Train students to be critical thinkers and readers.

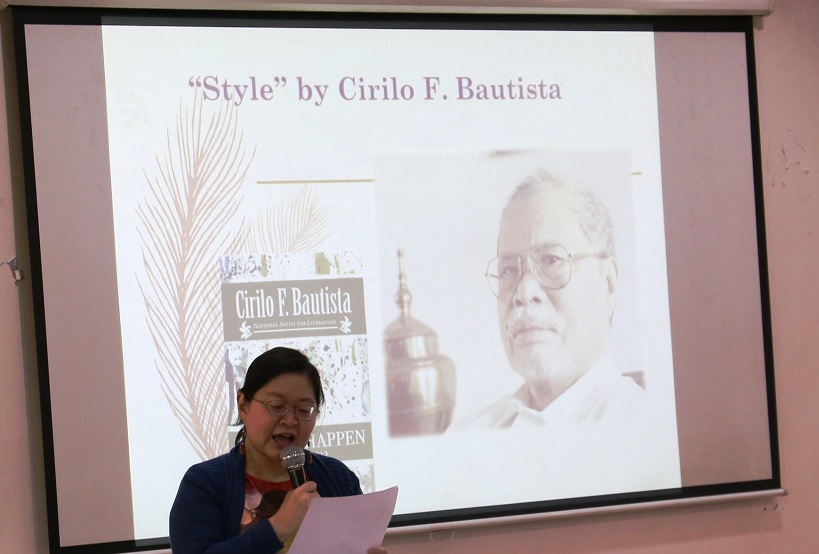

Shirley Lua reading aloud Cirilo Bautista’s poem

Lua defined close reading as “a slow reading and deliberate attempt to detach ourselves from the magical power of story-telling and pay attention to language, imagery, allusion, inter-textuality, syntax and form.”

She advised the teachers to engage their students in focusing on passages/verses, examining details (e.g., grammatical construction, punctuation, allusion and metaphor, etc.) to arrive at an interpretation.

She also said that poetry does not have to be concerned with “high-falutin ideas. What’s important is what strikes you to the core.” During close reading of poems, the teacher, she said, should guide the students to see and imagine or “sharpen their metaphoric consciousness. This means linking unlike objects. What differentiates poetry from prose is indirectness and suggestion.” In short, the abstract is concretized.

She cited the country of Columbia which holds the International Poetry Festival in Medellin. Festival organizers believe that, she said, “if a child knows poetry, he will not hold a gun in his hand.” (Columbia was once home to violent drug cartels.)

Lua also listed the 21st-century themes and issues that the teacher can tackle: climate change; identity, class, ethnicity and gender; diaspora and globalization; current issues like extra-judicial killings, war and conflicts; and social media and technology.

She explained the “poetics of pain,” quoting American poet Edward Hirsch who wrote, “We might say that the madness of any country’s brutality has often wounded its poets into poetry.” She said the Philippines could claim a “literature of pain” because of its history of colonialism, imperialism, despotic regimes and natural disasters.

Shirley Lua with Baguio-based playwright Malou Jacob

“We have been wounded by history,” she said, noting how not enough writing is being done about World War II, martial law and linking this to EJKs as a way of “voicing out the wounds of history to make new history.”

She said, “By reliving the pain to achieve freedom, the poet becomes witness to the history of trauma.”

She also said poetry “encourages students to reflect more in relation to their own selves.”

Lua stressed that in a classroom setting, “poetry is not meant to be read silently with the eyes, but it is created to be heard or performed.” Examples of how a poem can be performed are: choir recitation, audio-music suite, video, singing.

To further dramatize the verse/s verbally or non-verbally, she enumerated these ways:

- Physicalize the words;

- Enact selected verses;

- Recite accompanied by mime or dance;

- Take a snapshot or create a tableau;

- Transform the poem into a story and enact it in the form of a skit;

- Do verse echo to emphasize important lines;

- Translate and recite.

By performing a poem, she said students “discover the mnemonic quality of the poem which helps us remember it. We don’t want poetry to be silent, to be muted.”

A class can also organize a poetry festival wherein poems can be performed in a garden, in an amphitheater or elsewhere “so it becomes a part of our lives,” Lua said.

She concluded, “We have a strong tradition in poetry, and it should not change just because we are speaking in a language we adopted.”

The Philippine PEN workshop in Baguio was borne out of the 2010 PEN Congress in Cebu wherein a resolution was passed to “work more closely with the education sector, its leaders, planners and administrators, its teachers and students, and the education publishing industry, to improve literature education in the country. The Philippine PEN recognizes that literary taste is shaped in the schools, especially the public school system; it is where generations must be taught to appreciate the outstanding works of our very own writers, works that constitute the soul of our nation.”

Workshops had been held also in Manila, Iloilo, Cebu, Naga, Bohol, Calbayog, Cagayan de Oro, Iligan and Davao. The workshop series was supported by PEN International, Clifford Chance Foundation and the Swedish International Development Cooperation Agency.