Images provided by M.L. Camagay and National Historical Commission

Offering an invaluable insight into the lives of working women, the revised edition of Working Women of Manila in the 19th Century by Ma. Luisa Camagay. University of the Philippines Press, 2024 reminds us that Filipino women represent a formidable pool of talent and capability whose full potentiality remains untapped to this day.

The book documents the lives of these women, in seven occupations: cigarreras (tobacco factory workers), matronas titulares (licensed midwives), maestras (teachers), criadas (female domestic workers), tenderas and vendedoras (store owners and vendors), costureras and bordadoras (seamstresses and embroiderers), and mujeres públicas (prostitutes).

A mind of their own, assertive, active, and enterprising — these women workers run counter to stereotyped and idealized notions of Filipino women as shy, weak, and subservient, as the Spaniards would have wished.

Unseen and invisible in history, it is the only work on women that uses primary documents on women such as the vecindarios or the list of inhabitants in Manila (Intramuros) and its suburbs in 1886-1887.

Into factories

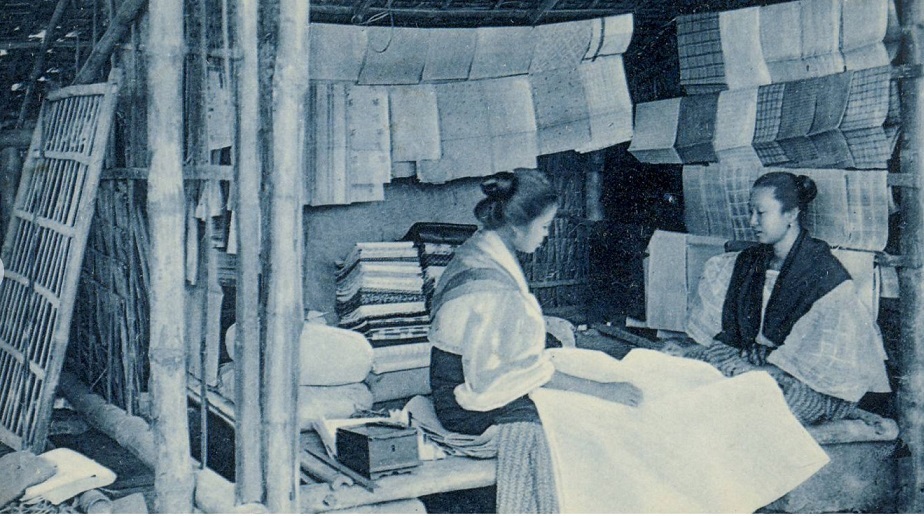

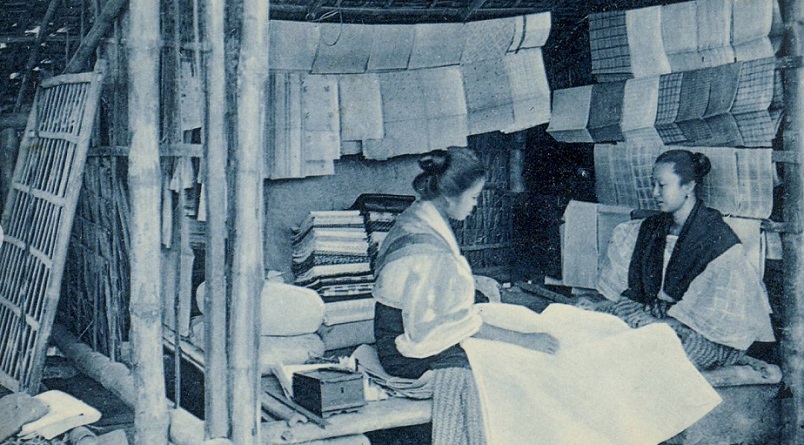

The first factory workers of Manila, thousands of women worked as cigarreras and ranked first among the occupations of women, with 30,000 by the end of the 19th century. The Spanish government established the Tobacco Monopoly (1781-1882) that introduced the factory system.

The four tobacco factories in Manila preferred women because of their skill in rolling cigars; most of all, they were considered honest, and not prone to smuggling cigars out of the factory.

They would be bodily searched twice a day, at noon when going home for lunch and at the end of the day, a practice done in many retail establishments today. Badly rolled cigars and overweight ones would incur penalties; losing a day’s wage was the usual punishment.

Later, some cigarreras were sent to Surabaya, Indonesia to teach local women how to roll cigarettes in Dutch factories. Camagay calls them our first OFWs.

Voicing out grievances

The cigarreras engaged in mass actions and strikes (downplayed by the Spaniards as only alborotos or mere tantrums) to demand better wages and work conditions. They also objected to verbal abuses, public reprimands, and usurious practices committed by their immediate superiors.

Respect was important for these women; even female domestic servants made official complaints against their masters who maltreated them, verbally or physically.

The 19th century saw the entry of women into professions that required special training and licenses through examination: teaching and midwifery. The maestras went to the Superior School for Women, established in 1892; the matronas went to the School for Midwives, founded in 1879. After earning a teacher certificate, the title Doña prefaced a new teacher’s name. However, gender discrimination persisted with low wages of maestras compared to maestros.

Enterprising

Deprived of political rights and education, women workers supplemented the family income, as seen by the predominance of women vendors, shopkeepers, and embroiderers.

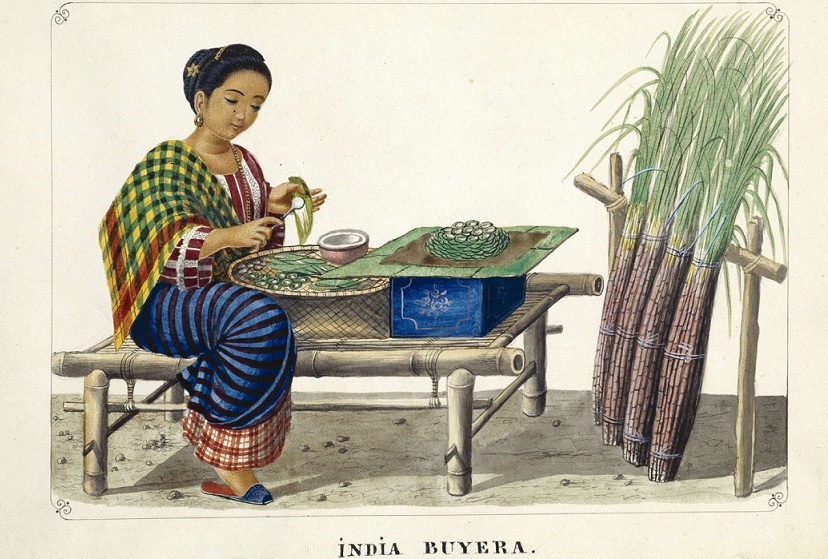

Walking barefoot with bilao on their heads, vendors included the buyera selling betelnut chew or the lechera or milkmaid who delivered carabao milk twice a day. They also sell also mats, clay pots, and rice by the ganta.

The female domestic servant, much fewer than male servants, were required to register with the police; most of them worked for rich Spanish families or foreign ones. Their practice of asking for a salary advance due to sickness or death in the family, suddenly leaving the household, or stealing money or jewelry were familiar ones, then and today.

Missing domestic helpers were advertised in the newspaper with a promise of a reward money.

Friar power

The friars dominated the lives of these women. A cigarrera must have a reference letter from her town’s parish priest when applying in a tobacco factory. The town priest acted as the local school inspector of the maestras. A reference letter from the town priest was needed to transfer from one teaching assignment to another.

The women had to deal with the persistent problem of sexual harassment, with the friar as the principal offender.

Today

Fewer Filipino women aged 15 and above participate in the country’s labor force compared to men, as of December 2023, based on Philippine Statistics Authority (PSA) data. Around 21.9 million women (56. 27%) compared with 30.2 million (76.97%) men are participating in the labor force as of December 2023.

Women earn more than men, says PSA. Female workers receive around 745.80 pesos daily basic pay; males get 720.65 pesos, according to the 2022 Occupational Wages Survey.

Women are mostly employed in wholesale and retail; repair of motor vehicles and motorcycles; and personal goods hygiene industry. More women than men are working overseas, mostly in Saudi Arabia. Of the estimated 1.96 million OFWs in 2022, 1.13 million (57.8%) were females, notes PSA.

The author

Maria Luisa T. Camagay is a professor emeritus in the history department of the University of the Philippines Diliman. A multi-awarded author, she has written the following books: Kasaysayan Panlipunan ng Maynila (1992), Working Women of Manila in the 19th Century (1995), French Consular Dispatches on the Philippines Revolution (1997), and The City with a Soul (2019) on Quezon City’s local history.