By PABLO A. TARIMAN

IF you want to explore the performing arts this summer and are not keen on music listening, the best way is to watch films on the lives of artists.

IF you want to explore the performing arts this summer and are not keen on music listening, the best way is to watch films on the lives of artists.

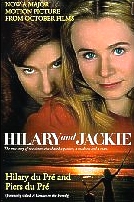

The best examples are “Shine” (about a piano prodigy and his Rach 3-obsessed father), “Hilary and Jackie” (about a celebrated cellist and her flutist sister), “The Piano Teacher” (about a Schubert interpreter with a wild streak of obsession and jealousy) and perhaps “Music of the Heart” (about a music teacher introducing classical music in the public schools in New York).

The film impact of “Shine” and “Hilary & Jackie” was revealing even among non-music aficionados. Perhaps one way to improve musical education in this country is to expose both young and adult audiences to quality films revolving around the life of musicians.

If the themes of love, intrigue and obsession are common, they are even more pronounced in the musical world.

Competition between voice teachers and their pupils reached absurd, if, comic, proportions in the Belgian film, “The Music Teacher” directed by Gerard Corbiau. The battle of tenors in the film reminded me of real-life rivalry between sopranos who had the same colorful teacher. Meanwhile, the subject of illicit love and labor unrest in the orchestra world were given satiric expression in “Meeting Venus.”

” One fine film that didn’t quite make it to Manila was Music of the Heart” which is about a violinist (Meryl Streep) who bravely introduced classical music in the public schools of Harlem where black parents didn’t want their children to “waste their time on the music of dead white men.”

If “Shine” showcased the immense power of the piano, “Hilary & Jackie” certainly scored a lot of musical points for the relatively unpopular cello.

Anand Tucker’s Hilary & Jackie is about two musically gifted sisters, one a flutist played by Rachel Griffiths and the other, the celebrated English cellist, Jacqueline Du Pre, played in the movie by Emily Watson.

Anand Tucker’s Hilary & Jackie is about two musically gifted sisters, one a flutist played by Rachel Griffiths and the other, the celebrated English cellist, Jacqueline Du Pre, played in the movie by Emily Watson.

The movie has enough informative concert scenes to make the viewer curious about this musical instrument called the cello. There is one backstage scene after Du Pre’s Wigmore Hall debut when a rich admirer gifted her with a Stradivarius Davidoff (1712) cello, which costs more than a million US dollars.

The film also allowed non-music lovers to realize that the cello – though not as popular as the piano and the violin – is gaining more acceptance in the performances of Filipino cellists like Wilfredo Pasamba (he organized an all-cello ensemble at St. Scholastica’s College and is, in fact, the first cello graduate of the Moscow Conservatory, the first Filipina piano graduate of which was Rowena Arrieta), Ramon Bolipata, Renato Lucas and that brilliant scholar from the Philippine High School for the Arts, Victor Michael Coo, who won rousing cheers for his cello debut with the Manila Philharmonic Orchestra under Rodel Colmenar. Fact is the Elgar cello concerto played in the movie by Watson was heard live for the first time in the Philippines some years back with cellist Renato Lucas, who was the soloist of the Philippine Philharmonic under Oscar Yatco.

Rostropovich – under whom Du Pre studied from January to May 1966 in Moscow – was heard in Manila in the 80s playing the Dvorak cello concerto after which former First Lady, Imelda Marcos gave him a distinguished International Artist citation. But the most touching message of the film is the question: is there life after concertizing?

Du Pre was a highly revered, world famous musician. But as the film showed, she was miserable in private life because she also longed for moments that have nothing to do with music – like loving moments with her sister, Hilary, and romping in the fields with her nephews and nieces. When Jackie noted that her sister was happy even without music because of a loving, caring husband, she wanted to share her happiness to the extent of asking her sister that her husband make love to her as well.

The late Marilou Diaz-Abaya, who cried after watching Hilary & Jackie in Germany, said one of the film projects she did consider was a story on young musicians. One of the few ideas in her drawing board before she passed away was a story about gifted children.

Abaya confided once: “I am actually looking at the little lives at the National Arts Center in Mt. Makiling and I am asking the question: what is sacrifice in the altar of art when you have a special child?”

Why did she want to do it at all?

The parting shot: “Because I am not a frustrated writer, but … I am a frustrated musician and that’s the reason why I am finicky with the music in my films.”

But will the composite lives of Cecile Licad, Lea Salonga,Lisa Macuja Elizalde, Otoniel Gonzaga, Conchita Gaston and Zeneida Amador make sense to moviegoers of this generation?

With the success of “Shine” and “Hilary & Jackie,” it is the turn of other arts-conscious filmmakers to make this elusive film on the arts a reality.