HISTORY is often told in broad strokes, but at times the real story is in the details.

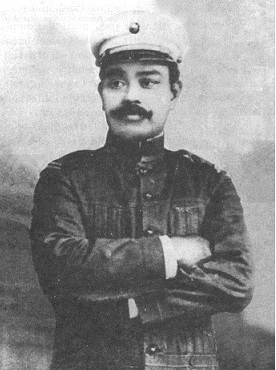

Philippine school books routinely depict General Antonio Luna as the hot-headed general who commanded the nascent Philippine Army during the Philippine Revolution and the Philippine-American War that followed. Filipinos are told that his death on June 5, 1899, was a tragedy — that he was assassinated by soldiers from his own army.

Why Luna died at the hands of his own countrymen is a fact that rankles Filipinos to this day. It resonates with the present also because it was an unsolved crime. And like many unsolved crimes in the Philippines today, people have an idea who the mastermind was.

That Luna was killed by troops of the Kawit Battalion is uncontested. The unit was composed of men who hailed from Cavite Province and were loyal to General Emilio Aguinaldo, the Philippines’ first president. Luna had earlier disarmed and arrested the battalion for insubordination as well as humiliated their commander, Captain Pedro Janolino.

That Luna was summoned to the town of Cabanatuan, Nueva Ecija, by Aguinaldo supposedly to form a new cabinet is uncontested. Curiously, Aguinaldo was nowhere and Luna found the Kawit Battalion instead.

Luna also ran into Aguinaldo’s foreign minister, Felipe Buencamino. deemed by Luna as a traitor. In one cabinet meeting, Buencamino advocated a compromise with the United States and Luna, adamantly opposed, knocked him down when the debate got heated.

What could not be proven was Aguinaldo’s involvement, which he denied until his dying day in 1964. Aguinaldo’s mother was allegedly there when it happened. The rumor goes that she called out from a window just outside where Luna fell. “Nagalaw pa ba iyan (Is he still moving?),” she said — allegedly.

No one was brought to justice. But, at least, the crime didn’t escape the judgment of history. Today, tourists visiting the Aguinaldo mansion in Kawit, Cavite, the birthplace of Philippine independence, speak about the Luna assassination in hushed tones out of courtesy — or not at all.

As depicted by the newly released movie “Heneral Luna”, the fiery general’s story is much about the Filipino and all his faults than it is about one of the most enigmatic figures in the Philippines’ history.

“Heneral Luna” is one of those films in which everybody already knows the ending. However, as the movie’s producers want to point out, the tragedy of General Antonio Luna still continues. History is repeating itself over and over.

The film is about the Filipino at his worst — his inability to rise above his self at the expense of the nation, and how his loyalties run along personal, familial, political, tribal, provincial, regional and parochial lines. That same shallow mentality bedevils Philippine society and politics today.

Luna understood the concept of nationhood that escapes many Filipinos even today.

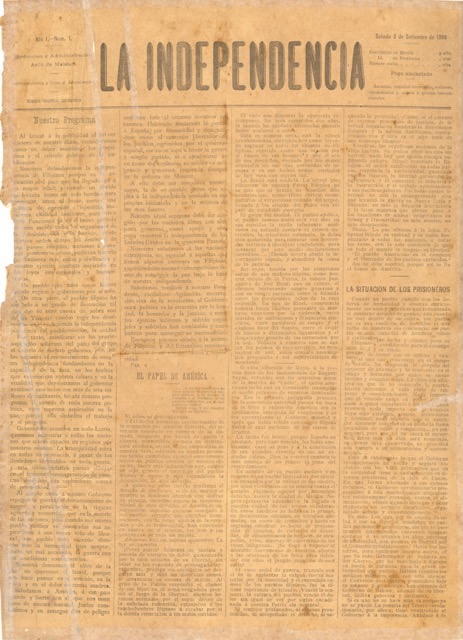

After the declaration of Philippine independence, he saw that the success of the new republic depended on the mindsets of his countrymen. He felt that the revolution needed a newspaper that would help mold the nation. On September 3, 1898, the first edition of La Independencia (“The Independence”) rolled off, thereby pioneering the democratic concept of freedom of the press in the Philippines.

As chief of the army and the only one with knowledge of military science, all Luna cared about was professionalizing the armed forces — a very familiar issue to Filipinos today — and kicking out the invading American troops as the United States began its annexation of the Philippines in late 1898.

He was a strict disciplinarian like the Spaniards of his day. So much so that his officers and troops nicknamed him “General Articulo Uno”, in which serious cases of insubordination were punishable with summary execution under the military code of conduct.

Luna foresaw a war with the United States when America refused to recognize Philippine independence. Anticipating a switch to guerrilla warfare to blunt the superiority of the US forces, he planned to establish a fortress in the rugged terrain of Mountain Province. The objective was to turn US public opinion against the conflict by waging a war of attrition and inflicting American casualties.

What Luna didn’t see was that the real threat lurked within his ranks and that the Americans were the least of his worries. To his critics, he was only an intellectually arrogant man with an erratic temper. Luna fervently believed in the ideal of nationhood fostered by the Philippine Revolution — which he initially argued against as premature — and it killed him.

When the end came, all he could say to his murderers was: “Traidores! Cobardes! Asesinos!(“Traitors! Cowards! Assassins!”)

That may not mean much today with the erosion of “delicadeza” or sense of propriety, as exemplified by many Filipino politicians. But in Luna’s day, they were the worst that could be said of any man. “Hiya” (“shame” in Filipino) was a very big deal because Filipinos valued their names and reputations. Therefore, to be “walang hiya” (“shameless”) meant losing “face” in the eyes of society.

Even today, quarrels among Filipinos easily erupt over the slightest slights, real or imagined — especially when it comes to issues of personal honor.

An American general, Robert Hughes, gave what may be the most fitting tribute to Luna that was also an indictment of the Filipinos. He remarked upon hearing of the assassination, perhaps perplexed by the dysfunctional dynamics of Filipino culture: “They had only one general, and they killed him.”

XXX