Text and photos by ELIZABETH LOLARGA

A sabbatical from his work as a professor at the University of the Philippines Baguio has enabled Delfin Tolentino Jr. to see that the poetic muse had fled although this may be temporary. The passion for books, however, remains like the constant wife it is to bibliophiles like him.

Among the reasons he cited for that year-long leave was a desire to return to creative work. In his artist’s statement to “Bric a Brac,” his latest exhibition of book art at Mt. Cloud Bookshop, he describes how “years of doing research and administrative work had throttled me. Writing memos, official letters and scholarly papers in often turgid prose had brought on a form of disquiet. It was time I stilled the soul.”

From what he called “the accumulated impedimenta of many years” that he found in his study, he has re-applied old but unforgotten skills in constructing books that are one of a kind or in limited editions of two or five.

Briefly, the interest in book art-making in Baguio grew when American visual artist Nancy Pobanz held workshops on the craft in the late’80s to the ’90s. She even taught participants to make paper from scratch or compost materials. Tolentino was among those who continued with book art-making with solo (this is only his second) and group exhibits in and out of Baguio.

He has taken book art to a higher level, bringing in the riches from a full academic life steeped in literature, film, the study and collection of material culture. His reputation as a wit and a raconteur seeps through the pages of the books that have both imagery and text. One is Culture with a Capital C in Gay Paree. French philosophers-literary theoreticians Michel Foucault, Jacques Derrida, Jacques Lacan, Helene Cixous, Julia Kriteva, Roland Barthes are depicted uttering risque thoughts. He assures in the colophon that this irreverence is “obviously intentional.”

In Kabuki Stars sa Minami-za at Iba Pang Engkwentro, he appropriates and manipulates pictures of elegant Japanese women in their traditional kimono. Underneath the images are captions that break the solemnity of what is portrayed. Tolentino freely uses the language of the streets in describing what’s going on, e.g., “Hanep sa hair-do ang mga kabuki stars na ito sa Minami-za” or “Jingle lang ang pahinga sa dalawang geishang ito na naglalaro ng go.”

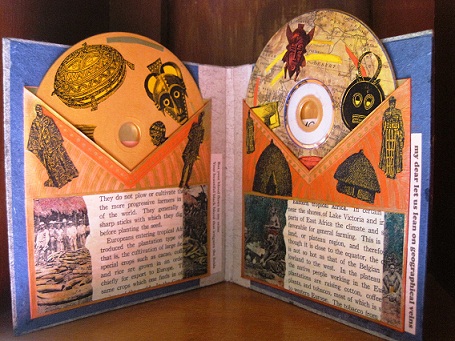

When a viewer-handler-reader opens a Tolentino book in the age of Kindles and e-books, the experience feels like a throwback to medieval times when monks worked on and embellished illuminated manuscripts. Except that this time the post-modern magus is equipped with a computer, a laser or inkjet printer plus an entire cabinet or a cache of ready-made wonders.

The wonder is how commonplace some of his materials are: postcards, bookmarks, bone pendants, playing cards, chip boards, newspaper scraps, elastic bands, postage stamps, linen threads, pieces of hemp, encyclopedia clippings, discarded compact discs, a phone card. All these things are upturned, pasted, stitched, punched holes into, tied, totally and lovingly transformed into close to magical things.

One wants to exclaim, “Behold! He makes all things new!” The newness is in his playfulness when he shares with viewers what he calls “the merry juxtapositions, the violations of historical and geographical accuracy, the disregard for original meanings, in short, the pleasurable transgressions of pastiche.”

Two slender books with the common subtitle of Kilroy Was Here on the subject of the bookmark are each introduced with a brief exposition on the use of a bookmark to mark a reader’s place. Tolentino notes how a book culture is not yet the norm in a Third World country. The reader thus is likely to use anything handy (a bus ticket, a grocery receipt, a business card) to mark the page where he/she means to return after a pause.

In the second volume, he segues into a meditation on leaving a trace, on mortality and death. The introduction brings to mind what Susan Sontag once said about what reading had done to her: “It enlarges your sense of human possibility, of what human nature is, of what happens in the world. It’s a creator of inwardness.”

This is where the book acquires its poignancy. Tolentino writes of how his father, a wide reader like himself, used postcards as bookmarks. One postcard peeked out of the pages of a book, Robert B. Parker’s A Catskill Eagle, that the older Tolentino was reading before he died. That bookmark was left in its place inside the book, stored away since, to remember “one reader’s final place before his soul soared to the high heavens.”

“Bric-a-Brac” is on view until March 7. Mt. Cloud Bookshop is inside Casa Vallejo, upper Session Road, Baguio City.