When the U.S. nonprofit Freedom House released last week its report on the state of internet freedom across the world, the detail most highlighted by many local media outfits was the “keyboard army” paid up to P3,000 to “manipulate the online information landscape” to support President Rodrigo Duterte.

While calling the problem alarming, an advocate said this only signals an underlying issue that the report, “Freedom on the Net 2017,” seems to have missed: the nature of political engagement in social media.

“When you go online, you see the inequality,” Lisa Garcia, executive director of nonprofit Foundation for Media Alternatives (FMA), told VERA Files, citing problems in the country’s internet freedom such as unequal access to content online, gender gap and poor literacy.

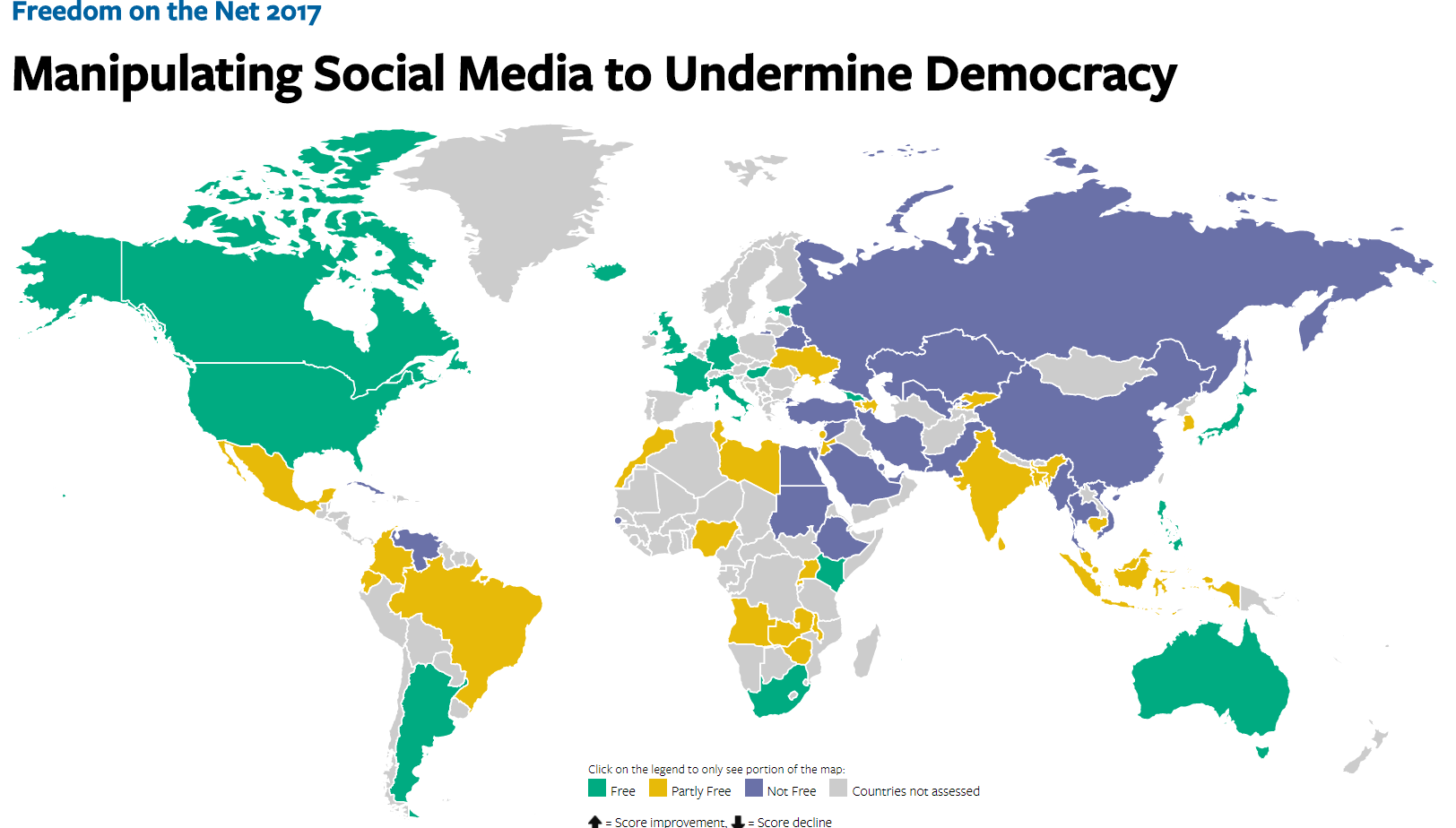

In the Freedom House report, the Philippines scored 28 or “free,” two points lower from 26 last year, with zero being most free and 100, the least.

Pinning the blame on steep subscription fees, the report said internet penetration improved but remains low at 55.5 percent, with connectivity concentrated mainly in urban areas.

The Philippines is one of 30 governments that have distorted information online, Freedom House noted, and added that fake social media accounts have operated to attack Duterte’s detractors before his election, and even now that he is in power.

In a statement, Communications Secretary Martin Andanar denied employing a keyboard army, saying, “What President Duterte has are millions of supporters, 16 million of which turned up at polling precincts throughout the land.”

The report of the Washington-based research and advocacy group also noted technical attacks, such as website disabling, used against some media outfits after publishing reports about the administration’s drug war. Other attacks, it added, target government institutions.

But when one talks of internet freedom in the country, these findings aren’t the only ones that should be highlighted, Garcia said, adding that the report should also include the problem of users who fall for fake news themselves.

“If I give you access, I give you connectivity, gadget, it doesn’t stop there. How would you use it?” she said, adding, “Literacy is important. Things like that, they should probably be mentioned, too.”

That journalists are being harassed on social media, as the report says, is not a new trend, but Garcia pointed out that other sectors, notably women, face the same problem.

“Even before, you can see attacks on certain groups like women who are vocal,” she said. “It’s either you walk out of it or you won’t comment. Those are the things that we are also looking at when we talk about issues of access,” she added.

FMA, which promotes use of information and communication for “democratization and popular empowerment,” said in its report released April that there’s a need to incorporate women’s voices in the government’s gender-sensitive programs.

“It’s important to us to mainstream gender. We believe the access to the internet isn’t equal yet,” Garcia said.

And it’s not only the marginalized who need briefing on the internet, but also lawmakers and judges who may seem out of touch with it, she explained.

Freedom House reported there is no systematic government censorship of online content in the Philippines, although it noted that online libel cases reached 494 in 2016, topping the list of cybercrime cases, with some resulting in imprisonment.

Garcia said, “Technology improves so fast, but it has its negative effects. How can we also train or give some briefing to legislators, so they would understand how technology is?”

She maintained that improvement of basic internet services is much needed, noting that many are still ill-equipped with the basic needs to navigate the net.

The administration has so far exerted efforts to bridge the gap, such as launching the National Broadband Plan under the Department of Information and Communication Technology, which targets all local government units be connected to the internet, Freedom House noted.

The government, it further noted, has been developing the P78-billion “Philippine Integrated Infostructure,” which would provide affordable internet services to unserved and underserved areas by 2020.

But Garcia hopes beyond free Facebook data, internet access can be free for all.

“In the future, why not? The cost of buying internet should be cheaper…Whatever opportunities are there, grab it,” she said.

In the meantime, she added that what people need now is guidance, which can start with schools teaching students how to be tech-savvy, and to combat disinformation.

“I hope it’s more than just the ‘these are the parts of the computer,’” Garcia added.