By ELLEN T. TORDESILLAS

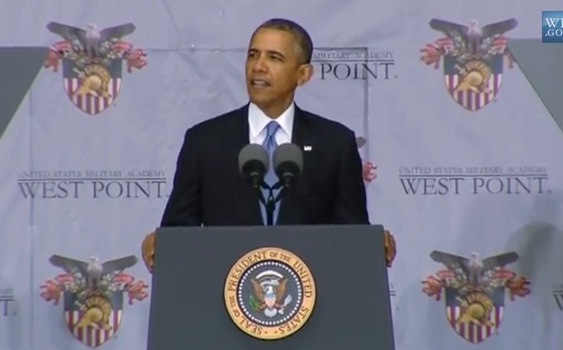

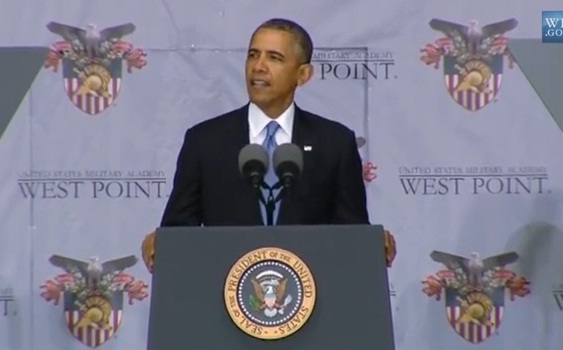

“JUST because we have the best hammer does not mean that every problem is a nail.”

“And I would betray my duty to you and to the country we love if I ever sent you into harm’s way simply because I saw a problem somewhere in the world that needed to be fixed, or because I was worried about critics who think military intervention is the only way for America to avoid looking weak. “

Those statements in President Barack Obama’s Foreign Policy speech at the commencement ceremony of the United States Military Academy last week should tell current Philippine leaders to rethink of their U.S-dependent foreign policy because America will not risk the lives of their soldiers to fight for a war that will put their national interest in jeopardy.

Here’s another part of his speech worth noting by those who look up to the Americans as savior from China’s aggressive actions in the South China Sea:

“First, let me repeat a principle I put forward at the outset of my presidency: “The United States will use military force, unilaterally if necessary, when our core interests demand it — when our people are threatened, when our livelihoods are at stake, when the security of our allies is in danger.”

Take note of Obama’s, and for that matter any U.S. President’s priorities: “our core interests” which he specified the first two as “when our people are threatened, when our livelihoods are at stake.”

The third should keep alive the hope of Philippine officials of American rescue in a battle with China: “when the security of our allies is in danger.”

But they should take note also of this part of Obama’s speech: “But to say that we have an interest in pursuing peace and freedom beyond our borders is not to say that every problem has a military solution. Since World War II, some of our most costly mistakes came not from our restraint, but from our willingness to rush into military adventures without thinking through the consequences — without building international support and legitimacy for our action; without leveling with the American people about the sacrifices required. Tough talk often draws headlines, but war rarely conforms to slogans. As General Eisenhower, someone with hard-earned knowledge on this subject, said at this ceremony in 1947: “War is mankind’s most tragic and stupid folly; to seek or advise its deliberate provocation is a black crime against all men.”

Many times in the past two years since the April 8, 2012 standoff with China at the Scarborough shoal or Bajo de Masincloc, the U.S. has been telling Philippine officials to tone down their anti-China rhetoric. American soldiers are not returning to the Philippines under EDCA (Enhanced Defense Cooperation Agreement) to fight with Filipino soldiers against China. They want to have their military bases here primarily to secure U.S. interest, whether it’s strengthening their capability to fight terrorism or making sure that freedom of navigation in the South China Sea is maintained.

A peaceful Asia Pacific that includes the South China Sea, is to the interest of everybody including the United States.

In fact, on July 5, 2012 the cabinet met on the situation in Scarborough shoal, where two Chinese ships remained even after the withdrawal of all Philippine vessels first week of June ending a 57-day standoff.

Majority of the members of the cabinet voted to send back the Coast Guard and Fisheries vessels to the shoal, 124 nautical miles from the coast of Zambales in Luzon. Malacañang, however, did not send back the ships as the United States advised against it. The United States is concerned about miscalculations on both sides which could trigger an armed fight that could destabilize the region.

To those who are pinning their hopes on the provision of the 1951 Mutual Defense Treaty that says, “Each Party recognizes that an armed attack in the Pacific Area on either of the Parties would be dangerous to its own peace and safety and declares that it would act to meet the common dangers in accordance with its constitutional processes, “take note of the last two words: constitutional process.

That means any decision by the President of the United States on sending troops to help an ally will have to pass through U.S. Congress.

In the part in Obama’s speech about South China Sea, he expressed exasperation with the Senate’s refusal to ratify the United Nations Convention of the Law of the Sea because Republican’s senators think that infringes on U.S. sovereignty.

Obama said:“ We can’t try to resolve problems in the South China Sea when we have refused to make sure that the Law of the Sea Convention is ratified by our United States Senate, despite the fact that our top military leaders say the treaty advances our national security. That’s not leadership; that’s retreat. That’s not strength; that’s weakness. It would be utterly foreign to leaders like Roosevelt and Truman, Eisenhower and Kennedy.”

That’s how democracy in the U.S. works.