Without fail every December, siblings Imee and Bongbong remind us on social media that were it not for their father, the late Ferdinand Marcos Sr, Filipino workers would not be enjoying their 13th month pay.

Marcos loyalists thus go to the extent of stating that those who are against the Marcoses should refuse to receive that holiday season benefit.

The ease of making that claim leaves out the dire context of why and how Ferdinand Marcos implemented the 13th month pay. And it erases the effort of organized labor to secure such a benefit for themselves.

Presidential Decree 851

Marcos, ruling by decree since he padlocked Congress when he assumed dictatorial powers in 1972, issued Presidential Decree (PD) 851 on December 16, 1975 “requiring all employers to pay their employees a 13th month pay.” Marcos’s misrepresentation started with that first line of the decree.

Marcos’s decree, and the propaganda that Imee and Bongbong wrapped around it, gives the impression that PD 851 started the practice of giving 13th month pay. It was not. Even before it was issued, some employers were already granting this benefit, that’s why Section 2 of Marcos’s decree states: “Employers already paying their employees a 13th-month pay or its equivalent are not covered by this Decree.” This exclusion states the obvious. However, while PD 851 did not apply to “all employers,” it also did not apply to all employees.

PD 851 was specifically for employees “receiving a basic salary of not more than P1, 000 a month, regardless of the nature of their employment.” They were to receive a 13th month pay “not later than Dec. 24 of every year.”

When the “Rules and Regulations Implementing Presidential Decree 851” came out a week after the edict was issued, Marcos kept whittling down those who will be covered by the law. Those who are not entitled to receive 13th month pay are the following: government employees, “household helpers and persons in the personal service of another in relation to such workers,” and “those who are paid on purely commission, boundary, or task basis, and those who are paid a fixed amount for performing a specific work” (meaning, most of the drivers in the public transport sector).

The implementing rules and regulations (IRR) of PD 851 provided an exemption for distressed employers, “such as (1) those which are currently incurring substantial losses or (2) in the case of non-profit institutions and organizations, where their income, whether from donations, contributions, grants and other earnings from any source, has consistently declined by more than 40% of their normal income for the last two years.” Their exemption must be approved by the Secretary of Labor.

The IRR also tried to correct a possible misconception by stating that nothing in PD 851 “shall prevent employers from giving the benefits provided in the Decree to their employees who are receiving more than P1,000 a month or benefits higher than those provided by the Decree.” It was an encouragement but not a binding mandate.

A month after issuing PD 851, Marcos was still tinkering with the law as he issued on Jan.16, 1976 the “Supplementary Rules and Regulations Implementing Presidential Decree 851.” The excuse given was “lack of sufficient time for the dissemination of the provisions of P.D. No. 851 and its Rules and the unavailability of adequate cash flow due to the long holiday season.”

What became obvious was that even among those select groups of employees that should have received 13th month pay, a significant number seemed to have not received it since the supplementary IRR ended up extending the due date for giving their 13th month pay for 1975 until March 31, 1976. The deadline, specifically for private schools, was even extended until June 30, 1976, a full half year since PD 851 had been in effect.

The supplementary IRR to PD 851 also excluded security guards or those employed by “Security and Watchman Agencies,” as well as contractors and subcontractors, at least for the year 1975. The supplementary IRR reasoned that their contracts for 1975 may not have a provision for a 13th month pay.

In the succeeding years, the implementation of PD 851 was challenged both by those it excluded and the employers that tried to exploit the ambiguity and omissions that inhere in the Marcos decree.

In the succeeding years, firms besides those enumerated in the implementation guidelines also applied for exemption to the Department of Labor from giving 13th month pay to their employees. Marcos issued a decree on May 1, 1978, Labor Day, to stop such exemptions, but expressly stated that the decree “did not apply to employers who are expressly exempted by law.”

A federation of government employees ran to the Supreme Court and contested their exclusion from receiving a 13th month pay but lost on Aug. 3, 1983 in Alliance of Government Workers et al. v The Honorable Minister of Labor and Employment et al. (G.R. No. L-60403).

As controversies arose regarding the implementation of PD 851, Marcos and his executive department became the arbiter on who may receive it and how. One particular voice was largely muted, if not missing from 1975 to 1981: labor unions independent of the regime, in particular those of the left.

Ordering employers to give 13th month pay should have been one of the carrots to the stick that Marcos lashed the organized labor with, with his decrees banning strikes, pickets, and lockouts.

Whose idea was the 13th month pay?

On May 1, 1974, Marcos issued PD 442, or the Philippine Labor Code. A team led by then Labor secretary Blas Ople was credited for developing the code. In his 1974 Labor Day address, Marcos said he had ordered Ople to “accelerate the codification of all labor laws” during the first Cabinet meeting after he placed the country under martial law.

In at least one interview after the fall of the Marcos regime, Ople described being “the author of the Labor Code of the Philippines” as among his greatest achievements. This issue of authorship, however, must be qualified by the fact that what Marcos (or Ople) did, as Ople himself wrote in the 1981-82 Fookien Times Philippines Yearbook, was to revise and consolidate “the country’s labor and social legislations.” They did not write it from scratch.

As quoted by Cherry-Lynn Ricafrente in a 1974 Philippine Law Journal article, Ople said that the Labor Code was “designed to be a dynamic and growing body of laws which will reflect continually the lessons of practical application and experience.”

Thus, through the martial law-era version of tripartism — involving the government and government-preferred representatives of employers’ groups and trade unions (only those with imprimatur of the Marcos regime), the last eventually forming what would become the Trade Union Congress of the Philippines (TUCP) — opportunities were given to selected members of the labor sector to suggest amendments to the Labor Code.

The Labor Code enshrined tripartism, stating that national, regional, or industrial tripartite conferences could be called by the secretary of labor “from time to time.” On Oct. 24-26, 1975, a National Tripartite Conference on the Labor Code was held at the Development Academy of the Philippines in Tagaytay City. The conference resulted in two of the three labor-related decrees issued by Marcos on Dec.16, 1975 — or at least that was how Marcos made it appear.

The first was PD 849. It amended PD 823, or the law banning strikes, picketing, and lockouts. PD 823 was issued on Nov. 5, 1975, in reaction to the infamous La Tondeña strike, which took place within the same time as the October 1975 tripartite conference. PD 849 allowed strikes and lockouts, but only under limited circumstances, and allowed the president to force compulsory arbitration when “in the public interest,” effectively putting a stop to an employee strike or an employer lockout.

The second edict, PD 850, was a lengthy piece of legislation amending dozens of sections of the Labor Code. The first “whereas” clause of the law adopted in toto what Ople said about the Code being “a dynamic and growing body of laws.”

Both PD 849 and 850, in the whereas clauses, acknowledged that those were products of tripartite discussions. The text of PD 851 did not. Yet a 1978 article in the Philippine Labor Review by Leonardo Q. Montemayor stated it plainly: “It is also from the discussions in this Conference that Presidential Decree No. 851 was considered.”

One of PD 851’s whereas clauses states that “the Christmas season is an opportune time for society to show its concern for the plight of the working masses so they may properly celebrate Christmas and New Year”— that is, giving another month’s salary is a social responsibility mandated by a benevolent dictator.

But given that PD 851 resulted from a tripartite conference, and that neither Ople nor Marcos seemed to have thought of legislating such a benefit prior to 1975, who can be credited with pushing for its enactment?

In recent years, the most well-known claimant to the title of “Father of 13th Month Pay” is Negrense lawyer/legislator Zoilo de la Cruz Jr. In 1975, he was president of the National Congress of Unions in the Sugar Industry in the Philippines, or NACUSIP. NACUSIP became a member of the government-recognized Philippine Labor Coordinating Center that eventually became TUCP in April 1975, ensuring that De la Cruz and the sugar workers represented by NACUSIP had a seat in tripartite discussions.

In an obituary written by Marchel Espina and published in The Freeman on Dec. 17, 2014, it stated that De la Cruz “conceptualized the 13th month pay, the Social Amelioration Program in the sugar industry and payment of cost of living allowance to workers in the private sector.”

In an article by Espina published in the Visayan Daily Star on Dec. 14, 2019, Zoilo’s son Ronaldo de la Cruz — who is now president of NACUSIP —, said that his father actually drafted the 13th month pay proposal, taking advantage of “his closeness to Marcos” and Marcos’s legislative powers. Such claims have also been repeatedly made in NACUSIP’s Facebook page.

Similar claims have also been made about another TUCP-affiliated labor leader who was a lawyer/legislator: Eulogio R. Lerum. According his profile in the Official Directory of the Constitutional Commission (1986), “Heading the labor delegation to the 1975 National Tripartite Conference, he sponsored the 13th month’s pay, 10 percent night work premium, 5 days annual paid incentive leave and payment by the employer of the 10 percent attorney’s fees in case of illegal withholding of wages. . . . Thru his efforts, the minimum wage was raised to P37.00 and the cost of living allowance to P17.00 daily.”

At the time of the tripartite conference, Lerum was known as a leader/president of the National Labor Union. He went on to become the representative of the labor sector in the Interim and Regular Batasang Pambansa and, with Ople, a member of the 1986 Constitutional Commission.

Marcos usually presented the 13th month pay decree without crediting anyone else for coming up with it. In Five Years of the New Society (1978), he claimed that minimum wages have in fact been increased by more than 100% [because] the actual minimum wage consists of the present basic minimum wages [and] additional compulsory compensations,” including the 13th month pay, which supposedly “represented an actual increase in basic pay of 8.3%.”

In a pamphlet titled “Gains of the Reformist Government (A Further Precis),” released in 1985, he said, “I have mandated reasonable wage increases to restore the purchasing power of our workers,” stating that wages had increased from “P6.00 a day” in 1965 to “P8.00 a day in 1972” to P57.08 per day for nonagricultural workers in 1984,” adding that such wages “have been boosted through a guaranteed 13th month pay and cost of living allowances.”

On Nov. 3, 1975 Marcos issued PD 823 stating that “it is the policy of the State to encourage trade unionism and free collective bargaining within the framework of compulsory and voluntary arbitration and therefore all forms of strikes, picketing and lockouts are hereby strictly prohibited.”

PD 849 went through the motion of somewhat loosening this draconian measure by creating stringent conditions when “any legitimate labor union may strike and any employer may lockout in establishments.” But the fact remained that Marcos wanted to buy industrial peace at any cost to shore up his so-called New Society.

The issuance of PDs 849, 850, and 851 was not only timed for the Christmas season so that Marcos made it appear that he was handing out “gifts” to the workers. It was also on Dec.16, 1975 that Marcos sworn in the officers of the just-founded Trade Union Congress of the Philippines (TUCP) at Malacanang.

Marcos’s grant of 13th month pay to a select group of workers through PD 851 must thus be read in this context. While it helped alleviate the workers’ economic difficulties, it was also a propaganda tool for the New Society.

Imelda Marcos’ 13th month pay amid economic crisis

By the 1980s, the economic value of Marcos’s supposed benevolence became negligible with the recurring rise in inflation and peso devaluation. In a chapter on Labor Standards and Economic Development (1996), Rene Ofreneo, a scholar on labor issues, noted that “from 1970 to 1979, the national income per worker in 1972 prices increased by about 23 % or roughly 2% a year, while real wages for the same period went down by 38% for skilled workers and 46% for unskilled workers.”

By 1983, the Marcos regime was in crisis mode triggered by the assassination of Ninoy Aquino. Ople, writing again for the Fookien Times Philippines Yearbook, conceded that “the past year was particularly difficult as worsening unemployment characterized the domestic scene. Mainly, as a result of contracting consumer markets in the developed economies, retrenchment measures adopted by local firms increased layoffs and labor turnover in all industry sector.”

As the workers kept on tightening their belt, the Marcoses were emptying the coffers of the republic to finance their frivolities.

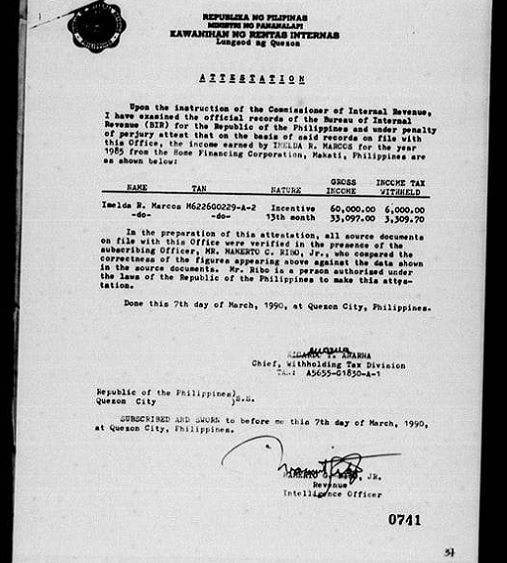

Some of them, like Imelda, also enjoyed her share of the 13th month pay as head of various government agencies and government-owned and -controlled corporations. In 1985, for example, Imelda, as head of the Home Financing Corp., received a 13th month pay of P33,097, based on records of the Presidential Commission on Good Government (PCGG). Anything beyond Imelda’s legal income — including 13th month pay — has been juridically determined to be ill-gotten wealth.

Marcos managed to skirt his own prohibition against government employees receiving 13th month pay via annual presidential decrees that granted the release of the same benefit but only for that particular year. An effective way to shore up his image as the workers’ unrivalled patron.

When Cory Aquino succeeded Marcos to the presidency, she introduced some changes that broadened the scope of PD 851, specifically on who are entitled to a 13th month pay. During her 1986 Labor Day address, Cory Aquino announced that she would remove the pay ceiling for the 13th month pay for all rank-and-file employees. On Aug. 13, 1986, she issued Memorandum Order 28, which fulfilled her Labor Day promise. However, the amended PD 851 still did not grant a 13th month pay to government employees.

This was finally remedied by Republic Act 6686, enacted on Dec. 14, 1988 which states: ”All officials and employees of the National Government who have rendered at least four months of service from Jan. 1 to Oct. 31 of each year and who are employed in the government service as of Oct. 31 of the same year shall each receive a Christmas bonus equivalent to one month basic salary and additional cash gift of P1,000.

Joel F. Ariate Jr. and Miguel Paolo P. Reyes are researchers at the Third World Studies Center, College of Social Sciences and Philosophy, University of the Philippines Diliman. Larah Vinda Del Mundo provided research assistance. This piece is part of their on-going research program, the Marcos Regime Research

The views in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of VERA Files.