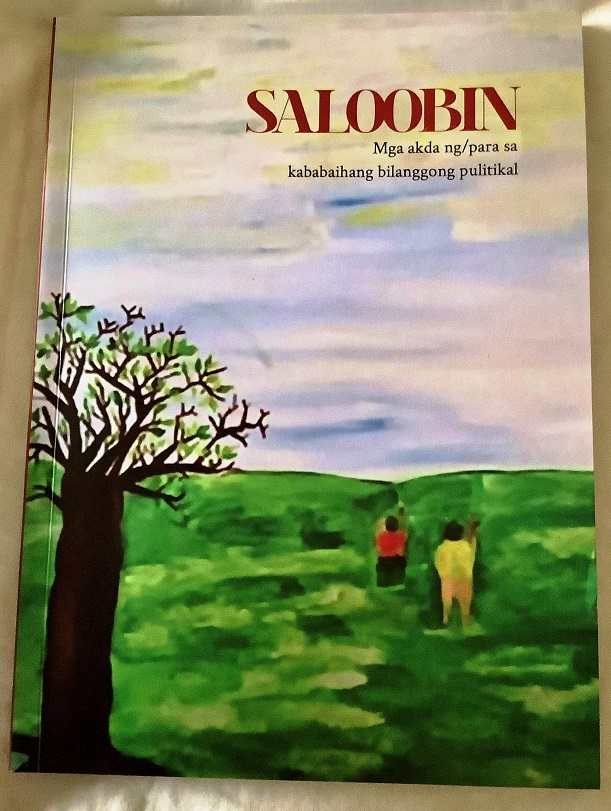

Artwork by Ani Luntian

There are now 715 political prisoners in the Philippines of whom 132 or around 18.5 percent are women. The figures are a scandalous rebuke against what is supposedly a liberal democratic society. Such a society may just be a masquerade for all the human rights violations that are taking place in a regime that is increasingly authoritarian.

What is worse, said Prof. Judy Taguiwalo, former political detainee during the Marcos dictatorship, is that the general public know little, and little is reported, about the numbers of those in detention and the circumstances of their arrest.

The earlier figures came from Fides Lim, spokesperson of Kapatid, an organization of families and friends supporting political prisoners and wife of longtime prisoner Vicente Ladlad. The occasion was the launch of the book SaLoobin: Mga Akda ng/para sa Kababaihang Bilanggong Pulitikal, published by Kapatid and the feminist organization Gantala Press, last Sunday, July 18, observed internationally as Nelson Mandela Day.

Lim said the publishers chose July 18 to launch the 144-page book to honor Mandela’s “legacy as a great statesman, humanist and peacemaker, and also to remind everyone, this government especially, about his long walk to freedom as a political prisoner for 27 years.”

She continued, “Mandela wouldn’t have been Mandela without those 27 years behind bars, the first 18 of which were spent at the brutal Robben Island Prison. It’s an essential part of his life that shaped his legacy. And it’s only fitting that after declaring July 18, Mandela’s birthday, as Nelson Mandela International Day in 2009, the UN General Assembly in 2015 extended its scope to promote the revised United Nations Standard Minimum Rules for the Treatment of Prisoners as the ‘Mandela Rules.’”

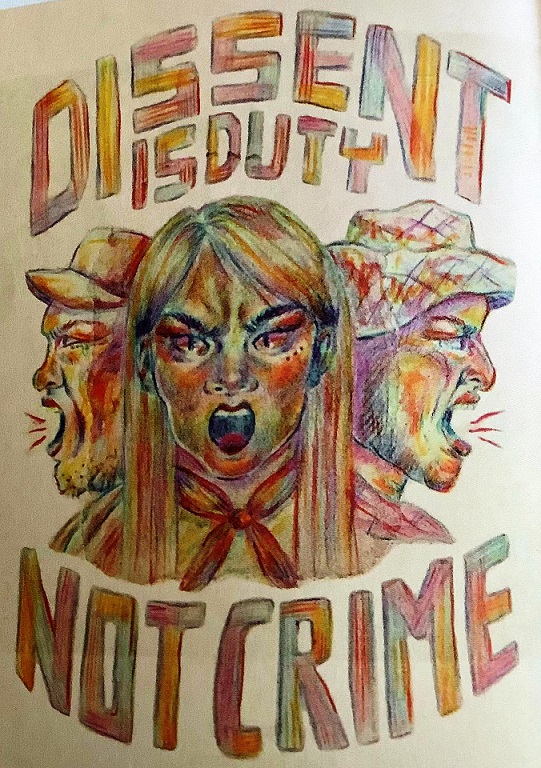

In its state of women political prisoners in the country, Tanggol Bayi-Philippines and Kapatid jointly stated and defined them as “individual women arrested, detained and imprisoned for acts in furtherance of their political beliefs. As a consequence, they are arbitrarily denied liberty and due process of law. They may be charged with political offenses such as rebellion, sedition and variations thereof, but more often than not they are charged with criminal offenses so as to deny the political nature of their alleged offenses and to stigmatize them as plain criminals guilty of the most heinous crimes. They are slapped with murder, multiple murder, frustrated murder, arson, kidnapping, robbery in band, illegal possession of firearms and explosives, and other offenses. These are all non-bailable crimes meant to keep them in prolonged detention while court hearings proceed at snail’s pace. This is also in keeping with the government’s objective of concealing the true extent of illegal arrests and detention suffered by political/social activists, government critics, dissidents and ordinary folk, and to paint them as ordinary criminals. Some of them were arrested when they were rendering care services for political activists, or they lived in communities where soldiers have encamped or were the site of military operations.”

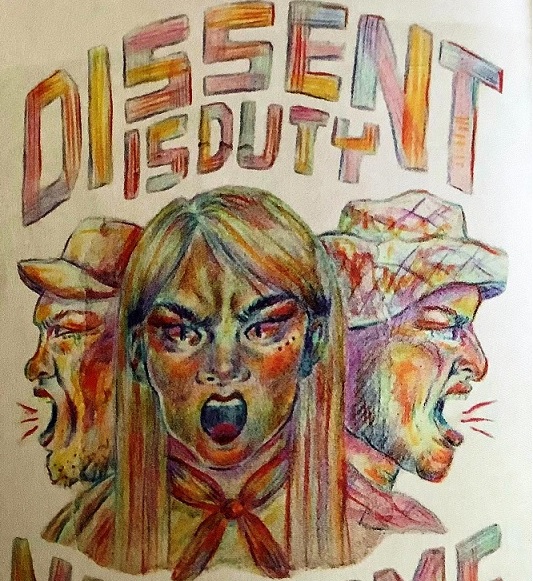

Artwork by @kill.joy.mall

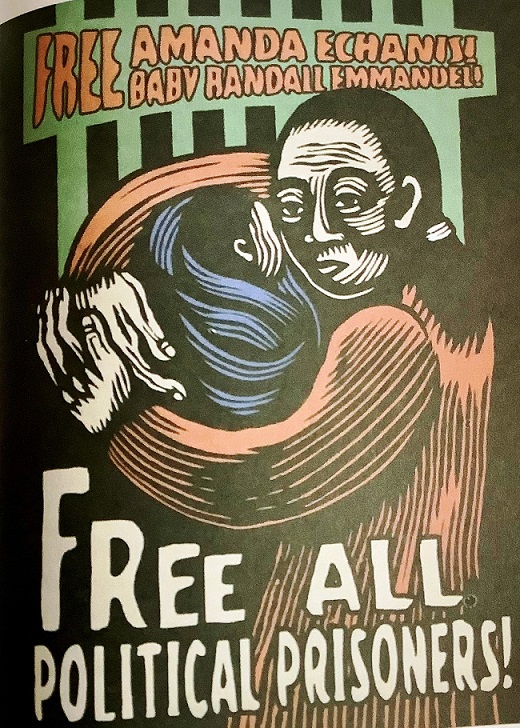

Sometimes, the women are wrenched from their still nursing babies and young children, which is what had led to the deaths of Baby River and Baby Carlen. The book’s title is derived from Alma Moran’s essay in Filipino “Sa(Loob)in” which begins and ends with the hopeful message: “Hindi laging hari ang dilim,” roughly translated to “Darkness is not always king.”

SaLoobin is significant because, according to Lim, it is “the first collection of political prisoners’ literary works to be published since Kapatid was revived in 2019.” It is also an almost all-women endeavor with not only “poldets” contributing poems, stories, songs and essays but also their supporters from outside the walls of prison.

The most famous among the women poldets is Sen. Leila M. De Lima who contributed the poem, “Pinay, Malaya at Nagpapasya,” which indicts the political bullies who have sought to silence her with accusations that she is an immoral woman.

The anthology also includes a portfolio of photographs of arts and crafts (e.g., crochet purse, embroidery) created while in prison. There is what seems like a rubbercut depicting mother and child Amanda Echanis and her baby Randall Emmanuel with a call to “Free All Political Prisoners.”

Contributing writers and artists are Reina Mae Nasino, Cora M. Agovida, Cleofe Lagtapon, Marites Coseñas, Lovely Jane Benigay Seronio, Teresita Abarratigue, Winona Birondo, Oliver and Rowena Rosales, Amanda Socorro L. Echanis, Karina Dela Cerna, Rani Urbias, Ka Tony, Sen. De Lima, Lim, China De Vera, Genevieve Soriano Aguinaldo, Jhio Jan A. Navarro, Maki Dela Rosa, Luchie B. Maranan, Rosario M. Gonzales, Sofia Bernice F. Navarro, Bernadette Anne Morales, R.B. Abiva, Marites Asis, Mara, Brenda Subido,NINARA-Youth, Szara (@_guhit), Virginia Villamor, Aleta Kim Garcia, Ani Luntian, @kill.joy.mall, Moran, Lady Ann Salem, Elina M. Velasco, Frenchie Mae Cumpio, Marilyn Magpatoc, M.R. Ampoon and Rae Rival with a message from Amihan National Federation of Peasant Women urging President Duterte to release political prisoners amid COVID-19.

The book is available at Shopeeor visit Gantala’s online store at https://payhip.com/GantalaPress.