Celebrating 100 years of broadcasting, Wika, Awit, Radyo, at Pananakop is a 30-minute documentary on broadcasting in the Philippines. It was launched through DZUP, the University of the Philippines’ radio station last June 29. (See DZUP’s FB page).

The documentary traces the early years of radio under American colonial rule (1898-1946) and under the Japanese occupation (1942-1945). Shaping the consciousness of the Filipinos according to American culture was done through radio: the spread of the English language and Western popular music in the country.

The early years

The first radio station (KDKA) in the United States started in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania in 1920; less than two years later, former American soldier Henry Herman consolidated his three experimental stations into one and called it KZKZ, the country’s first radio station and the first in Asia. As a U.S colony, four-letter call signs that start with KZ were used.

By late 1920s, there were two stations in Manila and one in Cebu. Department stores in Manila owned the prewar radio stations and used them to advertise their merchandise. For example, department stores IBeck was owned by DZIB; Erlanger & Galinger by KZEG. A good profit has always been the bottom line of the broadcast industry since its start.

Content: 1920s-1930s

Early radio was heavy on music, with an almost 70 percent share, especially American pop songs, dance music, and singing competitions. English was the predominant language used.

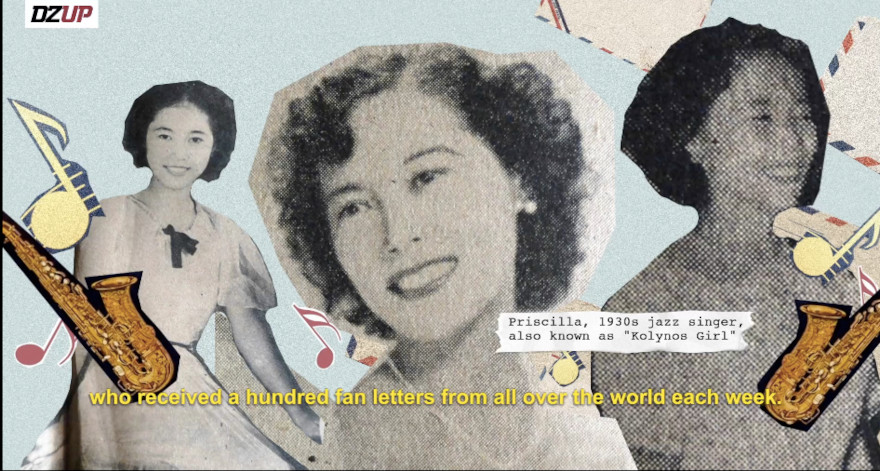

Filipinos quickly learned all the American songs, especially jazz. The most popular jazz singer in the 1930s was Priscilla, or the Kolynos Girl.

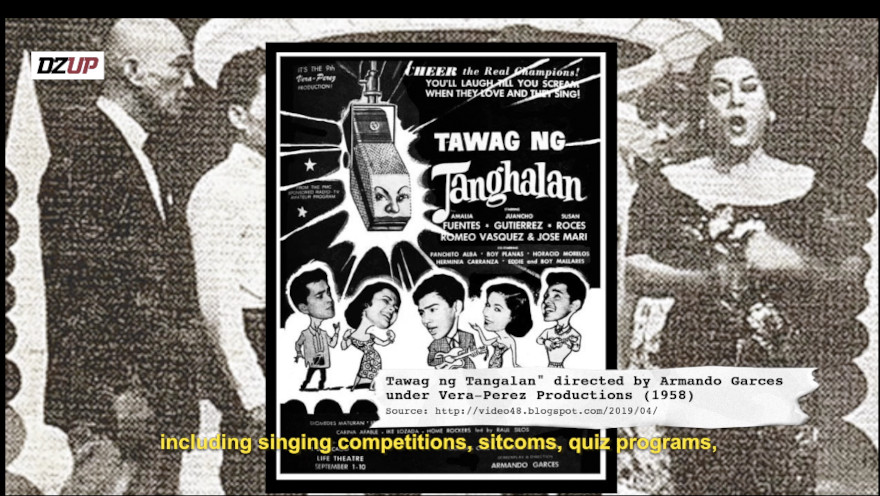

Program content included the playing of Filipino records; the live singing of kundiman and other Filipino songs; poetry readings and stage plays, short comedies, some interviews, sports competitions, a few minutes of news, and some live coverage of the National Assembly.

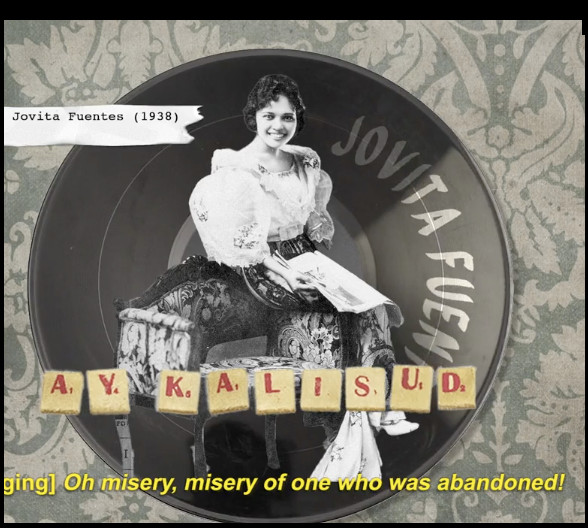

Some stations trained Filipino singers to perform live on radio; singers, pianists, bands, and even full orchestras performed live on air. Popular songs included Bituing Marikit, Kamuning by Atang de la Rama; and Ay Kalisud by Jovita Fuentes of Capiz, and a famous opera singer based in Europe. Both Fuentes and de la Rama were recognized as National Artists, in 1976 and 1979, respectively.

Advertisers buy radio time in blocks of 15 minutes and produce their own content, sparing the radio station of more expenses. Known today as blocktiming, this practice has persisted to this day.

By the mid-1930s, Tagalog had become strongly entrenched in radio, with a large audience of Filipinos who wanted to listen to songs by Filipino singers in their own language.

Under Japanese Occupation

Radio was also used as tool for Japan’s attempt to reshape the Filipinos, away from American culture and towards Asian culture, based on Japanese culture. Nihongo was taught in schools as well as on radio.

Under Japanese rule, radio programs became formal, serious, and rather annoying for Filipino taste such as the calisthenics program on Rajio Taiso, notes Enriquez. An unintended result of Japanese policies was the further strengthening of Tagalog and Filipino music on radio.

Post-war

Major American companies allotted a large portion of their budget to radio advertising. They also introduced and funded a new format —the soap operas (heavy on advertisements of laundry detergents and bath soaps) serialized everyday with a continuing storyline.

Drama and variety shows became the most effective in advertising daily needs such as soaps, cooking oil, toothpaste, etc. To entice viewers from all walks of life, Tagalog was used much more than English.

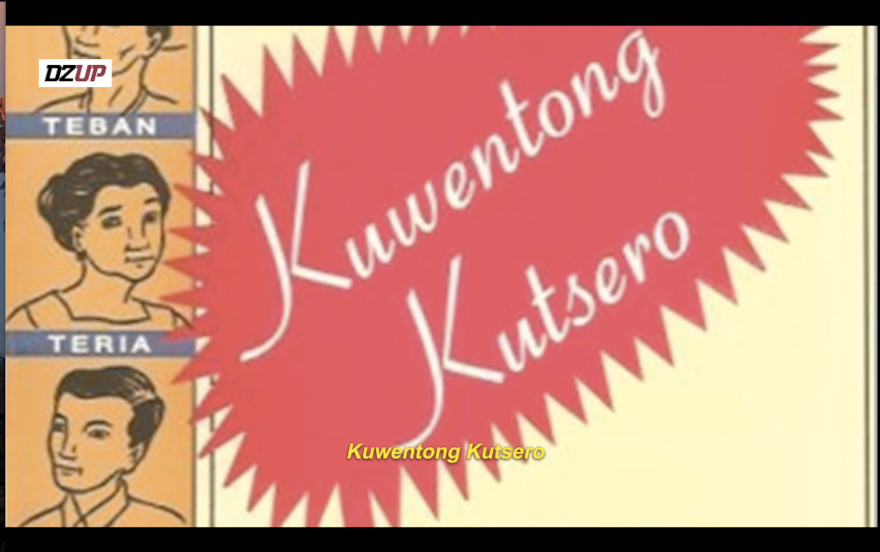

In the mid-1950s, the most popular live talent show was Kuwentong Kutsero, first aired in 1938, “a satire on Filipino manners, politics, customs and government.” (John A. Lent)

Music dominates

Many Filipino singers who sang in Tagalog became quite popular such as Ruben Tagalog. Outside of Manila, more radio stations proliferated, using Cebuano, Ilocano, Hiligaynon, or Ilocano.

The more than two decades after the war until the declaration of Martial Law in 1972 is considered the golden age of radio in the Philippines.

Today, Filipino languages and music continue to dominate in broadcasting (including TV and the new media). Simply, one’s own language and music remains in the innermost self, so difficult to erase and forget.

Radio reaches even the remotest part of the archipelago, untouched by television or the internet. In the latest Functional Literacy, Education, and Mass Media Survey (FLEMNS) of 2019—75.2 percent of Filipinos, 10 to 64 years old, listened to radio and 96.0 percent watched television.

Radio historian

The documentary is produced and written by Elizabeth L. Enriquez, PhD, and a professor of broadcast communication in UP Diliman. She is the author of Appropriation of Colonial Broadcasting: A History of Early Radio in the Philippines, 2009 and responsible for the pioneering volume on broadcast arts, CCP Encyclopedia on Philippine Arts, 2017.

As noted by the CCP Encyclopedia, broadcasting has forged “a nation of the everyday” and where “spaces for radical ideas have also been etched into everyday programming.”