By KHRYSTA IMPERIAL RARA

AS Filipinos celebrate today the 25th anniversary of the toppling of a 14-year-old military regime, hundreds of thousands of Arabs continue their street protests against overstaying dictators and monarchies in the Middle East and North Africa.

AS Filipinos celebrate today the 25th anniversary of the toppling of a 14-year-old military regime, hundreds of thousands of Arabs continue their street protests against overstaying dictators and monarchies in the Middle East and North Africa.

The massive protests began in Tunisia in December 2010. Demonstrators clashed with police in Algeria in late December to early January. Beginning mid-January, protest riots broke out in Libya, Yemen, Egypt, Sudan, Jordan, Bahrain, Oman and Morocco.

Like in the people’s Islamic revolution that drove out the Shah of Iran in 1979, the EDSA revolution that ousted dictator Ferdinand Marcos and the 1989 Velvet Revolution in Prague that overthrew the Communist government, the protesters in these Arab countries are seeking an end to inequality and a shift toward democracy.

For 35-year-old Aaron Sinsuat, witnessing and living the events in Egypt that led to dictator Hosni Mubarak’s ouster this month was a great learning experience. “I’m glad that I experienced a bit of what Filipinos must have felt in 1986,” said Sinsuat who was a fifth grader in Cotabato City during the EDSA protests.

“The Egyptians were hungry for change, freedom and democracy. I saw it in their eyes, in their smile. They were singing and dancing in the streets and even the children were there,” Sinsuat recalled. “It was a very emotional time for the Egyptians.”

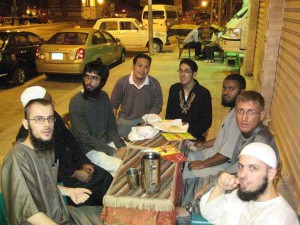

Sinsuat comes from a powerful political clan in Maguindanao, Mindanao. He worked for several years as segment producer in a leading television network before leaving to pursue Islamic studies and Arabic language at the Qortoba Institute for Arabic Studies (QIAS) in October 2009 in the Mediterranean city of Alexandria, the Egypt’s second largest city. One of the third batch of 36 Filipinos who opted for voluntary repatriation, he arrived in Manila on the eve of Valentine’s Day.

Sinsuat comes from a powerful political clan in Maguindanao, Mindanao. He worked for several years as segment producer in a leading television network before leaving to pursue Islamic studies and Arabic language at the Qortoba Institute for Arabic Studies (QIAS) in October 2009 in the Mediterranean city of Alexandria, the Egypt’s second largest city. One of the third batch of 36 Filipinos who opted for voluntary repatriation, he arrived in Manila on the eve of Valentine’s Day.

His studies were interrupted when the street riots began on January 25. The Cairo street rallies spread like wildfire to Alexandria and people took to the streets in the thousands. Classes were suspended and violence broke out in Cairo, Alexandria and other cities. Internet and cell phone services were cut off but the number of protesters just kept on growing, spurred on by word of mouth and news coverage aired on international media networks.

In retrospect, Sinsuat believes that the state of unrest in Egypt began when a car exploded in front of Al-Qiddissin Coptic Christian church on New Year’s Eve just as the midnight mass was about to end. Twenty-one people were killed and 70 wounded. Hundreds of angry Coptic Christians later clashed with police and Muslims while President Mubarak laid the blame for the bombing on “foreign hands” conspiring to destabilize the government.

“As a foreign student, I felt the uncertainty because of the presence of the military and secret police everywhere,” he said. “After the bombing, tuloy-tuloy na yung state of uncertainty.”

He recounted how police cracked down on foreigners living in Egypt, stopping them in the streets, pulling them aside and asking for their passports. He said it is easy to spot foreigners because of the way they carry themselves and their manner of wearing the thaub or the ankle-length white robe worn by most Arab Muslims.

“The police even came to our school and apartments. They showed us the picture of the decapitated head of the bombing suspect that was found near the Coptic church and asked each one of us if we knew him or had seen him before,” he said. “It was more convenient to put the blame on foreigners because of the repercussions if it were to be proven that the culprit was an Egyptian.”

For several years now, Egypt has been struggling to keep the country safe from the activities of Al-Qaeda and other so-called terrorist networks. “When I arrived in 2009, people refused to discuss politics because they were scared. The secret police was very powerful and you just didn’t know who they were. The people hated them. But they could be your neighbour, friend or even your brother.”

He described how Egyptians burned down the police stations. Although he considered Egypt as one of the safest places in the world, during the riots the only safe place to be in was home. There are about 4,200 overseas Filipino workers and students in Alexandria and most followed the advice of the Philippine Embassy to stay away from the streets.

“We lived on noodles, eggs and cereals for more than a week. There were no food deliveries to the grocery stores so there was nothing to buy,” he recalled.

When he and two friends went around town, a soldier guarding a big mall pointed his .45 caliber gun at them and demanded that they erase the pictures they took with their cameras.

Despite the panic-buying and looting, however, Sinsuat said the mood in the streets was “happy and not scary at all”. Some even challenged the security forces like their cab driver who hurled a water bottle at a parked police car.

He noticed that the change in the people’s disposition was quite electric. “Up to now, they are still exchanging stories about the rallies whereas before, there was zero talk about politics and no one wanted to mention Mubarak,” he explained.

Unfazed about what he experienced in Alexandria, Sinsuat plans to return to Egypt once the classes resume.