Natural dyes take center stage in the Likhang Habi Market Fair held Oct.8 through 20 with its theme “Earth to Loom: Celebrating Natural Dyes in Philippine Textile” by the Philippine Textile Council.

Natural dyes come from plants, animals, minerals, fungi, and bacteria. In the Philippines, traditional sources of dyes come from plants and its leaves, roots, bark, flower, and fruit.

Shades and hues

Many ethnolinguistic groups in the country use three sources of colorants: yellow ginger or turmeric for yellow dyes, morinda or noni tree for red dyes, and indigo for blue-black dyes.

Among the Maranao, yellow is considered yellow as a royal color with its yellow malong used by the Maranao elite. Aside from a natural colorant, turmeric is also used as food and medicine.

The Itneg/Tinguian refer to yellow ginger as kunig; among the Ilocanos, it is kuning or kuliyaw. Morinda is apator in Ilokano; sikarig among the Bagobo; and sakalig among the Mandaya. Indigo is kunarum among the B’laan; tayom for the Ilokano; and tayung-tayungan or tugun among Bicolanon.

Red remains a symbolic color for many of the Philippine indigenous peoples. The Bagobo’s famed inabal, a resist-dyed abaca cloth, takes its red from the roots of the morinda tree.

Red’s range of intensity, is expressed in the headcloth tangkulo of many Lumad groups in Mindanao and clothing of datus and bagani or warrior class. Among the Ilongot, red is associated with its concept of liget or energy, focus, or passion. Red upper garments are considered beautiful, as it focuses liget on the person’s face.

Red is also obtained from achuete or annatto seeds that also produce shades of orange and yellow; red narra tree, and a small tree, sibukaw or sappan tree and gaway-gaway or katuray tree.

From the leaves of talisay or tropical almond tree, yellow, gray, and black can be obtained; the husks of young coconuts produce shades of brown, pink, and mauve; guava leaves are sources of yellowish brown and golden brown; the fruits of the vegetable alugbati or Malabar spinach is also a source of purple and brown dyes.

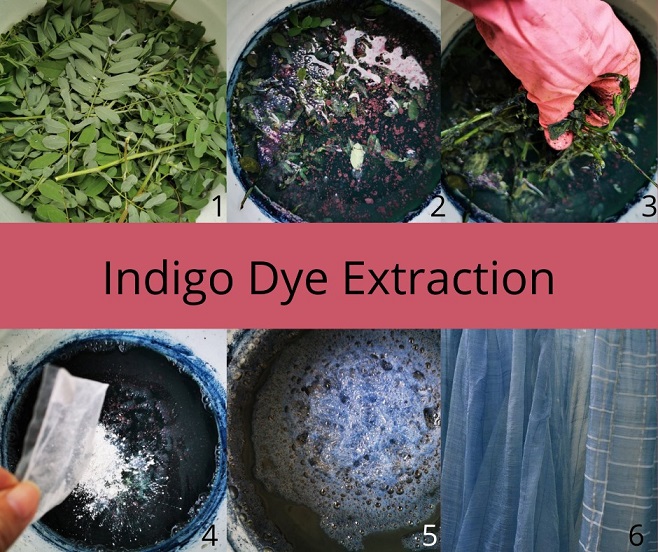

Indigo trade

Shades of blue, violet, and black can be extracted from the leaves of tayum or tagum indigo plant, one of the most popular and valuable source of natural dyes in the country. Today, Abra is considered as the natural dye capital of the country where indigo has been used for a long time.

Dyestuffs and other materials related to textile production were part of the trade goods exchanged for silk, ceramics, glass beads, silver, and other precious items through centuries of maritime trade with other peoples in Asia, including the Chinese.

Under Spain, indigo was exported to the Americas and Europe through the Manila-Acapulco galleon. The Ilocos was a major producer of indigo dye, as documented in historical records and the significant number of stone or brick indigo vats that still remain whole or in ruins in Ilocos Sur.

Today, indigo is commercially grown and processed into indigo powder in three areas: Abra, Occidental Mindoro, and Bukidnon; two areas in Antique and Rizal are involved in indigo cultivation and propagation. In August 2024, the Philippine Textile Research Institute (PTRI) has opened a second natural dye hub in San Remigio, Antique to complement the patadyong weaving industry.

More colorants

PTRI has documented over 100 sources of natural colorants that include bird’s eye chili or siling labuyo, lanzones, neem tree, guava, siniguelas or Spanish plum, and acacia tree. Other dye-yielding botanicals include bitaog or Indian laurel, bunga de china palm, cashew, castor plant, flame tree, Gmelina, golden shower, katmon, pagatpat, a mangrove species, pili nut tree, abutra, red onion, and rhoeo discolor.

Natural dyes are high-priced coloring materials that give distinct color to food, cosmetics, and textile materials that could be part of the country’s niche in the natural dyes export market, says PTRI.

Dyeing and weaving traditions

Natural dyeing has long been part of Philippine weaving culture. Knowledge of dyeing and its practices have been handed down from generation to generation among the country’s more than 182 ethnolinguistic groups.

Traditionally, the Hanunuo in southern Mindoro had used wild cotton for its backloom weaving, with cotton threads dyed using indigo to make garments like ramit, a skirt worn by women and a blouse or lambung, while balukas, the upper garment of men, is worn with a ba-ag or loincloth.

The Banton Burial Cloth is the oldest surviving specimen of textile in the Philippines dated 13th – 14th century; it is also the earliest known warp ikat textile in Southeast Asia. Naturally dyed in red and black, it was found in 1939 inside a cave in Banton Island, Romblon.

Philippine weaving culture can be traced back to 3,200 years, as evidenced by the spinning tools recovered from archaeological sites in the Batanes islands that have yielded 17 whole pieces and fragments of spindle whorls made of fired earthenware. Spindle whorls are part of a hand spindle, a tool used to prepare fiber into thread for loom weaving. Ancient spindle whorls have also been found in Cagayan and Palawan.