By NORMAN SISON

PAINTINGS are like stories sometimes. They are not simply works of the creative mind. They also have things to tell. But the details are hidden by the broad strokes.

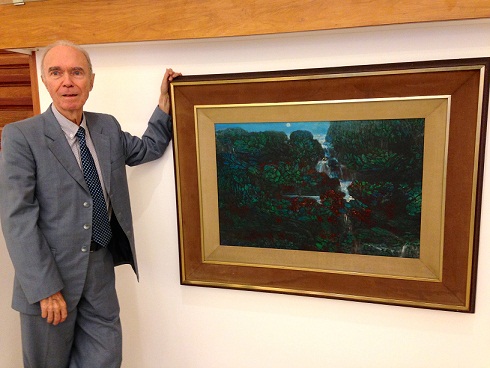

So it is at the newly inaugurated Museo Sanso in San Juan City. If the artwork there could talk, they would tell of the life — not just the artistry — of a Spaniard who calls the Philippines his home.

Caucasian and blue-eyed, it is easy to mistake Juvenal Sanso for a foreign tourist. But the moment he speaks, it is easy to see that he is Filipino in heart and mind. In fact, most Filipinos today weren’t even born when Sanso set foot in the Philippines.

His father moved the family from Reus, in the Spanish Catalonia region, to the Philippines in 1934 when Sanso was five years old. The Philippines was then a US colony and Sanso arrived just in time to see the country become an American commonwealth on the road to independence.

The Sansos put up El Arte Español, a wrought iron business. But being anti-fascists — Catalonia being a restive region as it still is today — they didn’t associate with other Spaniards.

Sanso grew up as children normally did, spending his boyhood in Manila’s Paco district and swimming in the river Pasig. He learned to speak Tagalog, played with other children and made friends. Among them was the future shopping mall tycoon Henry Sy.

His father put him through art lessons, thinking that the training would be of great use someday for the wrought iron business. That was when Sanso found his love for painting.

Sanso enrolled at the University of the Philippines School of Fine Arts. Among his professors were Fernando Amorsolo, Dominador Castañeda and Irineo Miranda.

Then came World War II. The horror and privation scarred him for the rest of his life.

The wrought iron business was ruined because Sanso’s father refused to cooperate in the Japanese war effort. Then came the 1945 Battle of Manila, which left the capital the second most devastated city in World War II after Warsaw.

Sanso was nearly killed when an artillery shell landed in their house in Santa Ana district. “I was blasted to the end of the room,” he relates. He is deaf in one ear today because of that.

A collection of paintings on the ground floor gallery of Museo Sanso is that chapter of Sanso’s life — a room full of nightmares. In colors of black, white and grays, the images of beggars are hideous and grotesque.

Among them is that of a beggar, sitting on the sidewalk, right arm outstretched and palm open. “Incubus” won first prize in the watercolor category of an Art Association of the Philippines competition in 1950. The following year, Sanso won the top prize in the oil category with “Sorcerer.”

Among them is that of a beggar, sitting on the sidewalk, right arm outstretched and palm open. “Incubus” won first prize in the watercolor category of an Art Association of the Philippines competition in 1950. The following year, Sanso won the top prize in the oil category with “Sorcerer.”

The second floor of the museum showcases the 50 years that Sanso spent in Europe, the Philippine art scene being limited at the time. He pursued further studies at the Academia di Belle Arti in Rome and at the L’Ecole Nationale Superieure des Beaux-Arts in Paris.

Like life returning to a tortured soul, Sanso’s works started having color as he painted scenes of France’s Brittany region. It was a healing of some sort from the trauma of World War II.

The Filipino in Sanso expressed itself in some of his work. He painted seascapes that clearly were of a foreign country but included elements that may be familiar to Filipinos, such as bamboo fishpens out in the water or the rocky coast of Calatagan in Batangas Province.

It was also abroad that Sanso made a name for himself. In 1964, his work “Leuers” was adjudged Print of the Year by the Cleveland Museum of Art, ranking Sanso alongside previous winners such as Henri Matisse and Salvador Dali.

“With a career that started from before World War II and a practice that includes exhibiting in Italy, Spain, France, the USA and the Philippines, Mr. Sanso’s body of work has picked up a lot of elements from the different cultures and the ideas of the times that he has been exposed to,” says Dida Salita, Museo Sanso’s director.

Today, Sanso’s works are in the collections of some of the world’s most prestigious museums such as the Baltimore Museum, the Brooklyn Museum, the Library of Congress in Washington DC, the Metropolitan Museum, the Museum of Modern Art, the New York Public Library, and the Smithsonian Institution.

The exhibit items on the third floor of Museo Sanso are quite noticeable compared to the works on the lower floors. They are in full color, mostly about floral arrangements.

Museo Sanso is not just about the man, however, says its curator Ricky Francisco. It is about imparting inspiration to aspiring artists, the same way Sanso discovered himself.

“Fundacion Sanso, which put up the museum, has been in the works for many years,” says Francisco. “The idea of opening a center to house the works and archives of Mr. Sanso for the public to enjoy has been brought up by the friends of Mr. Sanso. It is only now that things fell into place.”

At the far end of the floor is a collection of black and white and color photos about the artist, from his days as a dashing young man — a Spaniard in the Philippines — to the artist that he is today.

With a museum to house his works, Juvenal Sanso has come home.