By HARRY L. ROQUE

TWO years after the Philippines initiated arbitration proceedings against China under the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea, China belatedly published in the web site of its Ministry of Foreign Affairs its official Position Paper on the arbitration.

The Chinese position was divided into three.

First, that the UNCLOS ad hoc arbitral tribunal has no subject matter jurisdiction since what are involved are maritime territories generated by land territories;

Second, that the arbitration is in violation of the substantive obligation of the Philippines to negotiate with China the matter of the disputed islands and waters; and

Third, assuming arguendo that the Tribunal has subject-matter jurisdiction, it is still barred as a matter of delimitation which China has reserved from the jurisdiction of the UNCLOS dispute settlement procedure.

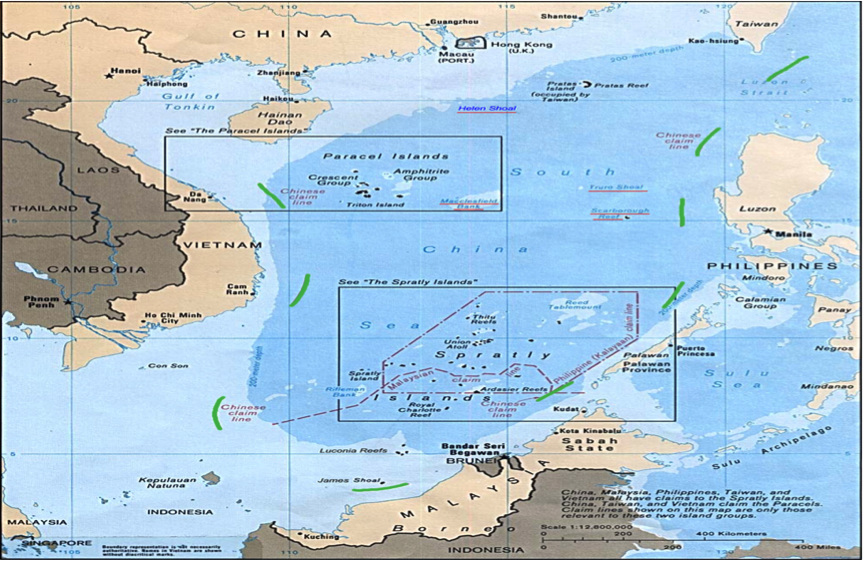

China reiterated that the waters within the contested nine-dash lines are waters generated by land territories. According to it, the Tribunal cannot act on the Philippine request to declare the said lines as contrary to UNCLOS without a prior determination of the validity of claims to land territories generating these maritime territories. And because the Philippine sought declaration would entail a legal conclusion on the validity of title over these disputed islands, the Tribunal, whose only jurisdiction is limited to issues of interpretation and application of the UNCLOS, is bereft of jurisdiction: “the subject-matter of the Philippines’ claims is in essence one of territorial sovereignty over several maritime features in the South China Sea, which is beyond the scope of the Convention and does not concern the interpretation or application of the Convention. Consequently, the Arbitral Tribunal has no jurisdiction over the claims of the Philippines for arbitration”.

Mirroring the language used by Judge Xue Hanquin in the Asian Society of International Conference in New Delhi last year who attributed to the Philippines a “design” and criticized the PH Statement of Claim as having “mixed up jurisdiction with the merits,” the position paper of China declares: “In an attempt to circumvent this jurisdictional hurdle x x x the Philippines has cunningly packaged its case in the present form. It has repeatedly professed that it does not seek from the Arbitral Tribunal a determination of territorial sovereignty x x x so that its claims for arbitration would appear to be concerned with the interpretation or application of the Convention, not with the sovereignty over those maritime features. This contrived packaging, however, fails to conceal the very essence of the subject-matter of the arbitration, namely, the territorial sovereignty over certain maritime features in the South China Sea.”

The problem with the Chinese view is that in essence, since all maritime zones under the UNCLOS are reckoned from land, then all maritime zones generated by disputed land territories cannot be the subject matter of any dispute involving interpretation or application of the UNCLOS.

Brought to its logical conclusion, the Chinese view would preclude any dispute to be brought to the UNCLOS dispute settlement procedure simply because water follows land.

This appears to be contrary to the object and purpose of the UNCLOS. Here, intention of the international community was to draft the ultimate constitution for the seas that would preclude resort to unilateral force in resolving these types of maritime disputes.

The better view is that despite the fact that all maritime territories are derived from land, the Tribunal should not be precluded from making legal declarations that certain claims to maritime territory are incompatible with the Convention.

Such forms of declaration will not resolve the issue of disputed title over land territory. It will, however, narrow the scope of the dispute and clarify the compatibility of the positions of the parties with the UNCLOS.

This is why even if the Philippines prevails in its relief and procures a declaration that the nine-dash lines is without legal basis, the issue of which state has title to the specific islands claimed by the parties will remain unresolved.

The ruling will however, clarify whether these disputed islands can generate only a territorial sea of twelve nautical miles or even an exclusive economic zone of up to 200 nautical miles pursuant to the rule under UNCLOS that only islands that can sustain human habitation can generate an EEZ. With this ruling, the scope of the dispute involving the disputed islands will now be limited to the island itself and the corresponding maritime regime it can generate.

For instance, while the Tribunal cannot rule on which state has title to Kalayaan and Itu Aba both of which have proven water source, the Tribunal can conceivable declare that only these two these two disputed islands, being the biggest in the Spratlys, can generate EEZ’s. All other disputed islands can therefore only generate a 12 nautical mile territorial sea, which would still be beneficial to the Philippines insofar as all the bodies of water not included in these territorial seas may pertain to the Philippines as part of its EEZ.

Neither is there merit in the Chinese position that arbitration is barred by the obligation to negotiate and by its reservation on matters involving delimitation. To begin with, it is clear under International Law that the obligation to negotiate does not extend to negotiations described by the International Tribunal on the Law of the sea (ITLOS) as showing “every sign of being unproductive”. Anent the delimitation, it is clear that none of the prayers of the Philippines involve delimiting either land or maritime territories.

Ultimately, China has to reckon with the fundamental issue of why it did not participate in the arbitration. It could have done so only for the purpose of making a preliminary objection on the jurisdiction of the tribunal. If China were half as confident as it now claims that the tribunal is without jurisdiction, it should have said so in the proceedings. Its non-participation in the end belies this confidence.