By ELLEN T. TORDESILLAS and TESSA JAMANDRE

Despite the presence of a high-level Philippine team at the hearing of the Philippines’ case against China before the Arbitral Tribunal of the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) this week, the issue of who owns the contested islands in the South China Sea will remain unresolved.

That’s because the Philippine team won’t be arguing its territorial claims, which are not under the jurisdiction of the Arbitral Tribunal in The Hague in the Netherlands.

“We are very confident that we can convince the court that this is not about ownership of land,” said former solicitor general now Supreme Court justice Francis Jardeleza, who is part of the Philippine team.

Instead, the Philippines merely wants the Tribunal, which interprets UNCLOS, to invalidate China’s 9-dash line claim over the South China Sea.

Territorial claims are the jurisdiction of another body, the International Court of Justice (ICJ), and the ICJ only entertains cases if all parties in the dispute participate. China has refused to do so.

But although the Philippines is not arguing about who owns what in the South China Sea, its arguments have been misconstrued as such. Jardeleza, in fact, said, “For example, we’re not asking the court to say who owns Panatag shoal. We are arguing that they are within our EEZ and therefore under the rules of UNCLOS we have exclusive rights to fish within that area.”

It is this posturing by the Philippines that China calls sly and cunning. Although saying it is not making a territorial claim before the Tribunal, the Philippines’ words practically establish ownership of islands and areas, the Chinese government said.

In its position paper submitted in December 2014, China said, “The Philippines has cunningly packaged its case in the present form.”

“This contrived packaging, however, fails to conceal the very essence of the subject-matter of the arbitration, namely, the territorial sovereignty over certain maritime features in the South China Sea,” China’s position paper adds.

The hearing at The Hague this week, however, comes at time of heightened tensions between the two countries, with China speeding up the reclamation of disputed islands in the South China Sea, even building on those the Philippines claims as part of its territory.

The top-level team of Philippine government officials preparing to face the Tribunal is composed of two Supreme Court justices, the leaders of Congress, and the secretaries of foreign affairs and justice, as well as the executive secretary.

The team includes Senior Associate Justice Antonio T. Carpio, who has been delivering lectures on the South China Sea conflict, and Jardeleza, who was solicitor general when the Philippines first submitted its memorandum to Tribunal on March 30, 2014. A memorandum is called a memorial in international law.

Also in the team are Senate president Franklin Drilon, House speaker Feliciano Belmonte, foreign affairs secretary Albert del Rosario, justice secretary Leila de Lima, and executive secretary Paquito Ochoa.

Leading the Philippine legal team are solicitor general Florin Hilbay and Paul Reichler, a Washington-based lawyer, who are expected to tell the Tribunal that the Philippines’ arbitration case against China is solely a maritime dispute and does not involve any territorial conflict.

The Philippines, in all its submissions to the Arbitral Tribunal, emphasized that it does not seek a determination on which party enjoys sovereignty over any of the insular features claimed by both but has confined itself to raising claims that require the interpretation or application of UNCLOS.

The Philippine has asked the Court not to “bifurcate” or divide in two parts the jurisdiction aspect and the merits of the case.

“There’s so much tactical advantage to that procedure because we are very strong on the merits and by discussing the merits more and more you gain an advantage hoping to convince the tribunal that they should take the case and rule that they have jurisdiction,” Jardeleza said.

Last April, the Permanent Court of Arbitration (PCA) that acts as a registry in the UNCLOS dispute settlement procedure, announced the hearing on the Arbitral Tribunal’s jurisdiction in the Philippine case versus China would be held July 7 to 13.

If the team is unable to convince the Tribunal, “that’s the end,” said Foreign Affairs Spokesperson Charles Jose.

But if the Tribunal rules it has jurisdiction, “It’s almost an 80 per cent chance of winning the case,” said lawyer Harry Roque, director of the University of the Philippines Law Center’s Institute of international Legal Studies.

China’s Dec. 7, 2014 position paper states: “The Philippines’ claims is in essence one of territorial sovereignty over several maritime features in the South China Sea, which is beyond the scope of the Convention and does not concern the interpretation or application of the Convention. Consequently, the Arbitral Tribunal has no jurisdiction over the claims of the Philippines for arbitration.”

Roque said the UNCLOS dispute settlement procedure is limited to “interpretation and application of the UNCLOS.”

“It is not involved in matters of sovereignty,” he said.

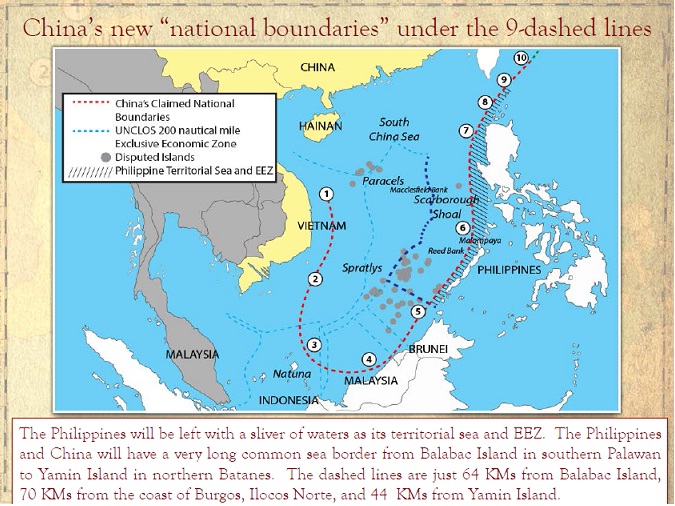

Carpio explained in one of his lectures on the South China Sea conflict, “The Philippines is asking the tribunal if China’s 9-dash lines can negate the Philippines’ 200 nautical mile exclusive economic zone as guaranteed under UNCLOS.”

“The Philippines is also asking the tribunal if certain rocks above water at high tide, like Scarborough Shoal, generate a 200 NM EEZ or only a 12 NM territorial sea. The Philippines is further asking the tribunal if China can appropriate low-tide elevations (LTEs), like Mischief Reef and Subi Reef, within the Philippines’ EEZ. These disputes involve the interpretation or application of the provisions of UNCLOS,” Carpio added.

Jardeleza said, “Our claim is a very narrow one, land dominates the sea. This is not a case about land; this is a case about the maritime waters which is perfectly under UNCLOS.”

The PH legal team is expected to justify its decision to seek compulsory dispute settlement after it has exhausted the negotiation tack, both bilateral and multilateral as required by UNCLOS.

China insisted in its position paper that “disputes between the two States shall be resolved through negotiations and there shall be no recourse to arbitration or other compulsory procedures.”

The team is also expected to tell the Tribunal that talks between the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) and China on the Code of Conduct on the South China Sea is inadequate, as its objective is to promote peace and stability in the region by coming up with a code on how claimants should conduct themselves pending resolution of the dispute.

Aside from Hilbay and Reichler, other members of the Philippine legal team are British law professors Philippe Sands and Alan Boyle and Bernard Oxman from the University of Miami’s Law school.

The five-member Arbitral Tribunal is chaired by Judge Thomas A. Mensah of Ghana. The other Members are Judge Jean-Pierre Cot of France, Judge Stanislaw Pawlak of Poland, Professor Alfred Soons of the Netherlands, and Judge Rüdiger Wolfrum of Germany.