(Conclusion)

THE permanent stationing of three of its ships in Bajo de Masinloc is part of China’s “creeping invasion” of disputed territories in the South China Sea, a high-ranking Philippine government official said.

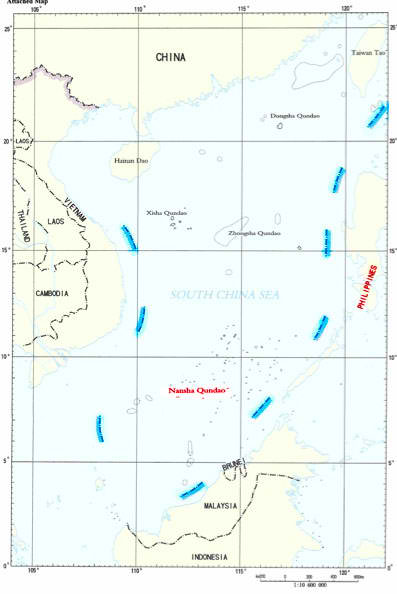

Bajo de Masinloc is Huangyan island to China, which has time and again reiterated “that Huangyan Island and Nansha Islands have always been parts of Chinese territory and that the People’s Republic of China has indisputable sovereignty over these islands and their adjacent waters.”

“The claim to territory sovereignty over Huangyan Island and Nansha Islands by the Philippines is illegal and invalid,” China says.

Nansha is what the Chinese call the Spratly Islands, a group of islands on the South China Sea, parts of which are being claimed by the Philippines, Vietnam, Malaysia, Brunei and Taiwan.

China’s presence on Bajo de Masinloc is also an alarming reminder to the Philippines of how Mischief Reef came under Chinese control 18 years ago.

In the early 1990s, China had built structures it said were just fishermen’s shelters on Mischief Reef. Through the years, China added installations on the island, including a radar system.

Philippine and U.S Air Force reconnaissance revealed military structures on Mischief Reef belying Chinese claims. In January 1995, the captain of a Philippine fishing boat reported that he was arrested and detained for a week by the Chinese when he ventured into Mischief Reef.

Since then Mischief Reef has been under the control of China and inaccessible to Filipinos.

A paper titled “Geopolitics of Scarborough Shoal” written by Francois-Xavier Bonnet of the Bangkok-based Research Institute on Contemporary Southeast Asia (IRASEC) explains the importance of Huangyan Island to the bigger and long-term objective of China.

Bonnet said Huangyan Island/Bajo de Masinloc is crucial to China’s claim over the Zhongsha Qundao islands which is vital in its controversial “nine-dash line map.”

The map is called “nine-dash line” or “nine-dotted line” because it shows a series of nine dashes or dotted lines forming a ring around the South China Sea area, which China claims is part of its territory. The area includes the Spratlys group and Bajo de Masinloc.

The “nine-dash line map” puts 90 percent of the whole South China Sea under Chinese jurisdiction.

The map does not have coordinates, but was submitted by China to the United Nations on May 7, 2009.

Bonnet explained, “The Zhongsha Qundao is composed of Macclesfield Bank, Truro Shoal, Saint Esprit Shoal, Dreyer Shoal and Scarborough Shoal. All these banks and shoals, except for Scarborough Shoal, are under several meters of water even during low tide. Chinese policymakers know too well that without Huangyan island, the chance of their ownership over Zhongsha Qundao recognized is nil.”

Bonnet explained, “The Zhongsha Qundao is composed of Macclesfield Bank, Truro Shoal, Saint Esprit Shoal, Dreyer Shoal and Scarborough Shoal. All these banks and shoals, except for Scarborough Shoal, are under several meters of water even during low tide. Chinese policymakers know too well that without Huangyan island, the chance of their ownership over Zhongsha Qundao recognized is nil.”

Bonnet said, “The stakes are high. If China loses Huangyan/Scarborough, it will lose Zhongsha Qundao, which could be divided by the EEZs of the neighboring countries or placed under the regime of the high seas. By consequence, China’s entire claim to the South China Sea supported by the U-shape line would be moot and academic.”

Last June, China elicited international concern when it established Sansha City on Yongxing Island in the southernmost province of Hainan. Sansha City’s territory includes the Spratlys, the Paracels and Macclesfield Bank.

Immediately after establishing Sansha City, China’s Central Military Commission, its most powerful military body, approved the deployment of a garrison of soldiers from the People’s Liberation Army to guard disputed islands.

China’s Ministry of Civil Affairs said in June that putting Macclesfield Bank, the Paracels and the Spratlys under Sansha would “further strengthen China’s administration and development” of the three island groups.

The Philippines protested the establishment of Sansha City, specifically the inclusion of a part of its territory, Macclesfield Bank, one of the largest underwater atolls in the world, covering an area of 6,500 square kilometers.

Former foreign undersecretary and Philippine Permanent Representative to the United Nations Lauro Baja said there is no doubt that China has Bajo de Masinloc in its long-term territorial design.

Incidents of Philippine Navy ships apprehending Chinese fishermen in the vicinity of Bajo de Masinloc is common. In 1999, the Philippine Navy even “accidentally” sank a Chinese fishing boat. But the conflict never went beyond the standard diplomatic protests.

Former Foreign Secretary Domingo Siazon recalled one apprehension in 1998 that was a subject of a diplomatic protest by China involving a young navy officer named Antonio Trillanes IV, who would would later on become a senator and play a controversial role in the tension between the Philippines and China over the disputed shoal.

But Philippine encounters with the Chinese in Baja de Masinloc took a different turn on April 8, 2012, when the BRP Gregorio Del Pilar, the Philippines lone modern warship acquired from the United States, arrested Chinese fishing vessels in the area.

Philippine military officials said BRP Gregorio del Pilar was due for preventive maintenance servicing in Subic at that time but was redirected to Northern Luzon as contingency undertaking for an impending North Korea rocket launch.

The combat ship was also ordered to verify reports about the presence of the Chinese fishing vessels in Bajo de Masinloc. They arrested Chinese fishermen in eight fishing boats caught with sizable quantities of endangered marine species, corals, live sharks and giant clams.

Looking back, officials say the April 8, 2012 incident gave China an excuse to occupy the area.

China immediately deployed three Chinese Marine Surveillance (CMS) ships to Bajo de Masinloc to rescue their fishermen and added more than 80 vessels as the standoff dragged on.

The Philippines later withdrew BRP Gregorio del Pilar, which was replaced by a Philippine Coast Guard ship and a research vessel by the Bureau of Fisheries and Aquatic Resources in observance of “white to white,” referring to civilian ships, and “gray to gray,” meaning navy-to-navy rules of engagement.

The standoff that lasted 57 days spilled over to the economic front with China rejecting inferior quality bananas from the Philippines and cancellation of Philippine-bound Chinese tour groups.

It was only broken upon the insistence of the United States State Department that the issue be resolved because President Barack Obama did not want it included in the agenda of his June 8, 2012 meeting with President Benigno Aquino III at the White House.

With the breakdown of communication between the straight-talking Philippine Foreign Secretary Albert Del Rosario and Chinese Ambassador Ma Keqing in Manila, U.S. Assistant Secretary of State for East Asian and Pacific Affairs Kurt Campbell proposed to Chinese Vice Foreign Minister Fu Ying in Washington D.C. that Chinese and Philippine vessels withdraw simultaneously from the disputed shoal.

By that time, Trillanes had entered the picture and was directly negotiating between Beijing and Malacañang to help de-escalate the tension.

Hours before Aquino left for London and Washington D.C. on June 4, 2012, Malacañang announced the pullout of Philippine ships from Bajo de Masinloc “consistent with our agreement with the Chinese government on withdrawal of all vessels from the shoal’s lagoon to defuse the tensions in the area.”

Diplomatic sources said Fu Ying never committed complete withdrawal of their ships from Bajo de Masinloc as there was resistance from the People’s Liberation Army, an important sector in China’s power structure.

Del Rosario said when he met with Fu Ying during her Manila visit last Oct. 19, “I was very direct in saying that the presence of their ships is in clear violation of our sovereign rights, and they must withdraw their ships at the earliest possible time.”

Fu Ying did not respond, he said.