Prepared by the Office of Representative Harry L. Roque Jr. Former Professor of International Law and Constitutional Law, University of the Philippines, College of Law, Former Director, Institute of International Legal Studies, UP Law, Center Vice-President for Southeast Asia and member, Executive Council, Asian Society of International Law

Introduction

The purpose of this primer is to inform the reader of the nuances of the case that is to be decided shortly in the arbitration between the Republic of the Philippines and the People’s Republic of China. By understanding the positions of China and the Philippines respectively, one can predict the outcome of the case, and come up with a plan of action for the Philippine government.

The Dispute: An Overview

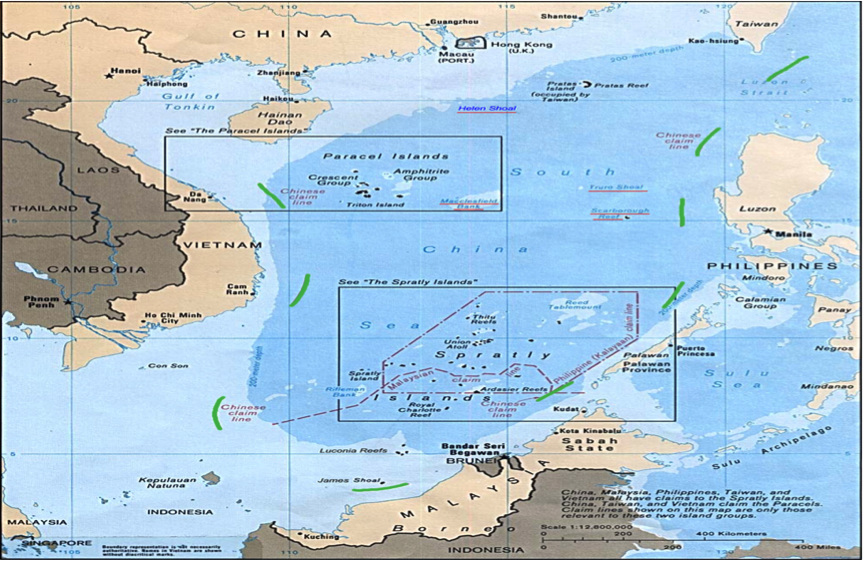

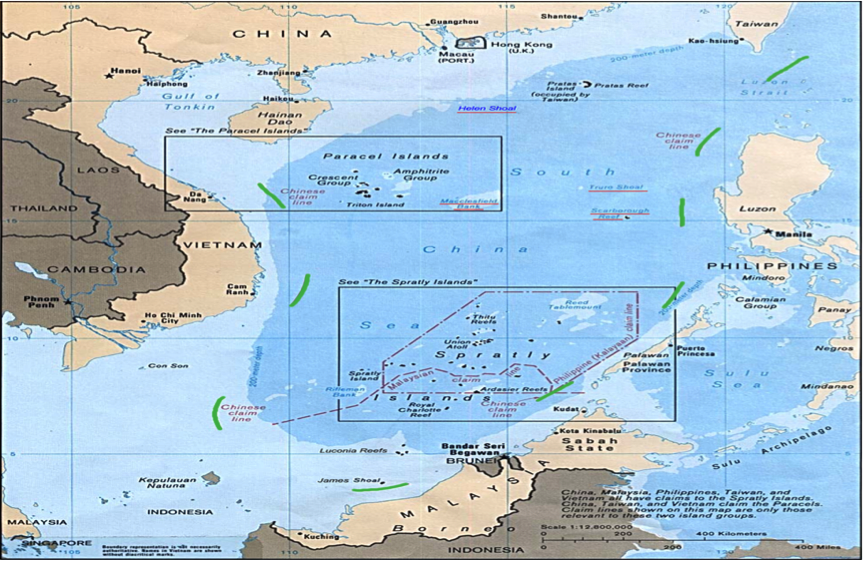

Under international law, every sovereign state has the exclusive right to explore and exploit the waters extending 200 nautical miles from its baselines – otherwise known as the Exclusive Economic Zone. The Philippine-China dispute stems from China’s alleged interference of the exclusive sovereign rights of the Philippines to its maritime entitlements under the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea.

Over the past few years, China has prevented Filipino fishermen from fishing around various locations or “features” within the West Philippine Sea. China has also constructed artificial islands and implements in areas claimed by the Philippines as part of its Continental Shelf and EEZ. The Philippines argues that all these actions are inconsistent with the rules laid out by the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), a treaty to which both States are state parties.

The dispute revolves around features such as the Scarborough Shoal, the Spratly Islands, and various reefs and reclaimed lands. These are encompassed within what is known as the “Nine-Dash Line” – an area China claims has always belonged to it in history.

On the other hand, the Philippines claims that the disputed features within this supposed Nine-Dash Line fall within its EEZ, measured off the baselines of Philippine territory – and thus China is in no position to prevent Filipinos to exploit the resources within them.

The Arbitration of the Permanent Court of Arbitration (PCA).

The Philippines filed the case against China before the International Tribunal of the Law of the Sea (ITLOS), a specialized international body dealing with disputes between states that are parties to the UNCLOS. The actual proceedings however, are being conducted by the Permanent Court of Arbitration (PCA), which acts as the registry for the ITLOS in the arbitral proceedings. As a body, the PCA has extensive experiencing hearing disputes under Chapter VII of the UNCLOS, which is the same part of the UNCLOs under which the Philippines brought suit against the People’s Republic of China.

China has refused to formally participate in the proceedings. However it has made public its arguments against the Philippine claim though various statements released to the public as well as through letters sent to the individual members of the Tribunal.

To its credit, the ITLOS has taken every effort to account for the Chinese position – though expressed largely through unofficial means, given the Chinese refusal to take part in the arbitration – in the submissions made by the Philippines.

On October 29, 2015, the PCA released two documents to explain that it had jurisdiction over the case between the Republic of the Philippines and the People’s Republic of China.

This ruling however, is limited only to the first phase of the arbitration, which concerns whether the arbitral body may actually hear the Philippine case. Thus in this ruling, the tribunal declared that it may proceed to hear the substantive arguments of the parties on several points.

The experience of other international tribunals shows that sometimes courts can very well rule in the preliminary or procedural phase that it has the jurisdiction to adjudicate the questions brought before it by the parties but hold during the merits or substantive phase that it has no jurisdiction to make any ruling on the substantive issues concerned. Thus, winning in the procedural phase does not guarantee winning in the substantive phase.

Recently, it was announced that the merits of the case will finally be decided and released by the first week of July 2016. In a few weeks, the PCA will finally resolve the substantive claims of the Philippines against China.

At this juncture, it is important to note the following: (1) the issues the arbitration will not address, (2) the issues to be resolved in the arbitration, and (3) the positions of the parties.

The Arbitration does not address which State has sovereignty or ownership over the features within the West Philippine Sea.

Although it seems as though the Philippines and China are simply arguing over who has title over the features such as the Spratly Islands, such is not the case.

Since the UNCLOS only deals with the law of the sea, any arbitration arising out of the rules under the UNCLOS are limited to such rules. Thus, the tribunal cannot resolve a dispute concerning sovereignty over land, or island for that matter.

Under international law, States may only claim title over lands or habitable islands. Strictly speaking, States do not exercise sovereignty over the waters or the seas – the UNCLOS merely provides or “delimits” certain rights to States, such as the right to explore or exploit the waters, otherwise known as “sovereign rights.”

Sovereign rights are not equivalent to full sovereignty or ownership of a state over a land territory or an island.

Where a state has full sovereignty, it may impose in the area found within its scope all of its laws and exercise acts of ownership in the area. The concept of sovereign rights however, deals only in general with a state’s right to exploit resources over a defined maritime area, to the exclusion of other states.

While sovereign rights may not be coextensive with full sovereignty, nevertheless, it is of exceeding importance in such an area as the West Philippine Sea teeming with oil and natural gas, as well as rich fishery stocks, not to mention extensive areas known for their rich biodiversity.

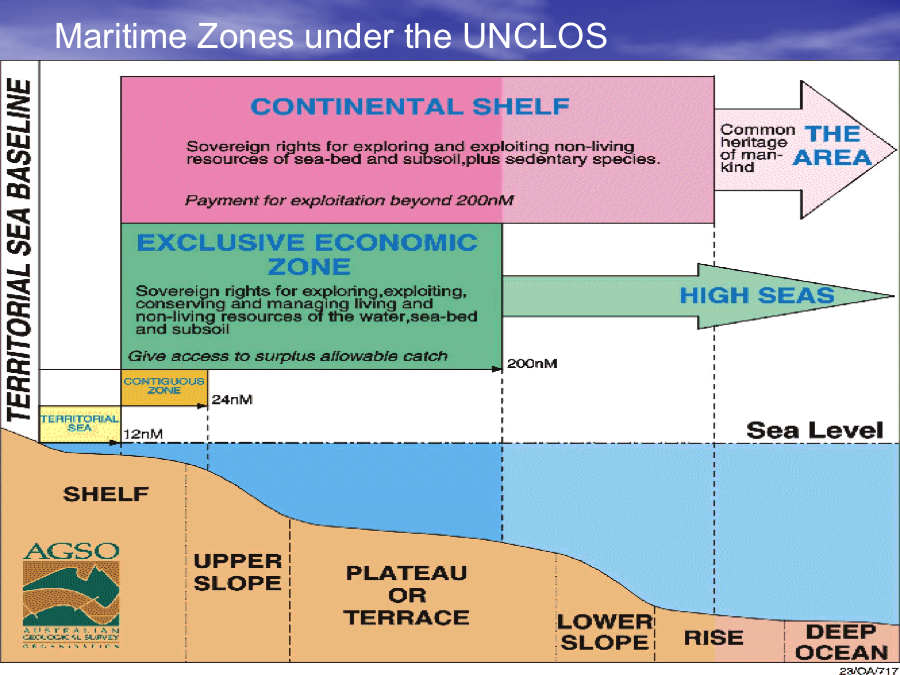

The UNCLOS provides that coastal States have sovereign rights to a Contiguous Zone, a Continental Shelf, and an EEZ, to be measured off the baseline of its territory.

The Contiguous Zone is an area extending for 12 nautical miles from the limits of the territorial sea or 24 nautical miles from the baseline. It is an area adjacent to the territorial sea where a state may exercise certain protective jurisdiction, such as customs enforcement, fiscal, immigration and sanitary rules.

The EEZ is an area adjacent to the territorial sea extending up to 200 nautical miles from the baselines from which the territorial sea is also measured. Within the EEZ, a state has sovereign rights to explore, exploit, conserve and manage natural resources, as well as build artificial islands, carry out environmental protection and conduct marine scientific research.

The Continental Shelf is the undersea natural prolongation of the landmass of a State extending beyond the territorial sea up to 200 nautical miles from the baselines of the territorial sea. It is coextensive with the EEZ, but may extend for another 150 nautical miles under the Extended Continental Shelf (ECS) Regime, depending on the presence of certain geological features.

Oil and natural gas are often found in the Continental Shelf.

Thus, the UNCLOS provides the rules for establishing a state’s maritime entitlements. It does not deal with the question of who owns land territories or islands for that matter. The issue of full sovereignty is determined by the rules of effectivite or exercise of sovereign acts – something beyond the scope of the current arbitration.

The Arbitration could determine the marine entitlements of the features within the West Philippine Sea

Without declaring which State exercises sovereignty over features such as the Spratly Islands, the PCA could, however, declare the legal entitlements of the features. In other words, while the PCA cannot say that a certain island belongs to China or the Philippines, it can however say that a certain feature is, in fact and law, an island.

According to the UNCLOS, an island is a “naturally formed area of land, surrounded by water, which is above water at high tide.” Additionally, islands must be able to sustain human habitation or economic life. Meanwhile rocks are protrusions those that cannot sustain human habitation or economic life.

If the PCA declares a certain feature to be an island, then the international community must respect all legal entitlements associated to such an island. Such would be entitled to a territorial sea, a Contiguous Zone, and Exclusive Economic zone and Continental shelf much like any other land territory. On the contrary, if a certain feature is merely a rock, it would only be entitled to no more than the 12 nautical mile-territorial sea.

The PCA may also hold that some of these disputed features in the West Philippine Sea are merely “low-tide elevations” which are part of the seabed and cannot be acquired by a state, unless they are part of its continental shelf. Nevertheless, the status of such elevations under international law is disputed vigorously by China.

What are the issues raised before the Permanent Court of Arbitration?

The issues of the arbitration can be summarized into two:

- Whether or not the Nine-Dash Lines are ineffective and inconsistent with international law?

- Whether or not the various features within the West Philippine Sea/South China Sea generate maritime zones under the UNCLOS?

- Whether or not Panatag island falls within the Philippines’ Exclusive Economic Zone

What is the Philippines’ position on the case?

The Philippine position, summarized, is as follows:

- China’s claim and exercise of sovereign rights pursuant to the supposed Nine-Dash Line is ineffective and inconsistent with international law, as the line exceeds maritime entitlements under UNCLOS;

- The Philippines is entitled to a territorial sea, an EEZ, and a Continental Shelf under the UNCLOS and to enjoy sovereignty and sovereign rights as appropriate to these maritime entitlements.

- The various features in the West Philippine Sea, such as Mischief Reef, Second Thomas Shoal, and others, are low-tide elevations that are not entitled to certain maritime zones under the Law of the Sea that China may lay a claim over;

- Accordingly, China’s acts of preventing Philippine nationals from enjoying its sovereign rights within these areas and those areas over which it is entitled under UNCLOS, as well as its alleged construction, exploration and exploitation activities are inconsistent with its obligations under the Law of the Sea.

- The Philippines has sovereign rights over the waters outside the 12 nautical miles of Scarborough shoal but within the 200 nautical miles of the country’s EEZ.

What is China’s position on the case?

Briefly, based on reports and statements made by Judge Due Hanquin of the Asian Society of International Law, the Chinese position is as follows:

- The arbitral tribunal has no subject matter jurisdiction since what are involved are maritime territories generated by land territories;

- Assuming arguendo that the Tribunal has subject matter jurisdiction, it is barred because it is a matter of delimitation, which China has reserved from the jurisdiction of the UNCLOS dispute settlement procedure.

Thus, the Philippines makes the following claims in regard to certain features in dispute (the Tribunals October 29, 2015 holdings on jurisdiction and admissibility of the claims are also presented):

| Features/claims in dispute | Location | Philippine Position | Tribunal’s ruling on jurisdictional issues

|

| The legality and validity of the Chinese Nine Dash Line Claim

|

Entirety of the West Philippine Sea | These are excessive and violate the maritime entitlements under the Law of the Sea | The possible jurisdictional objections with respect to the dispute does not possess an exclusively preliminary character as these may involve a discussion on historic bays and titles, which are outside the Tribunal’s jurisdiction. Accordingly, the Tribunal reserved a decision on its jurisdiction with respect to the Philippines’ for consideration in conjunction with the merits of the Philippines’ claims.

|

| China’s alleged

Interference with the Philippines’ petroleum exploration, seismic surveys, and fishing in what the Philippines claims as its exclusive economic zone as well as Chinese fishing within the same zone. |

Waters around the features in dispute | The Philippines is entitled to sovereign rights in these areas | The PCA reserved its ruling on jurisdiction on this point for consideration in the Merits phase, because of potential overlapping maritime entitlement claims with China (the presence of which h would entail a delimitation of boundaries, a process outside the Tribunal’s jurisdiction).

|

| Chinese fishing within the Scarborough Shoal | The Shoal is within the Philippines’ EEZ | To the extent that the claimed rights and alleged interference occurred within the territorial

sea of Scarborough Shoal, the Tribunal concludes that it has jurisdiction to address the matters raised in the Philippines’ claims.

|

|

| The dispute concerning the protection and preservation of the marine environment at Scarborough Shoal and Second Thomas Shoal

|

Both the Spratlys Group of Islands and the Scarborough shoal area | The Chinese has violated its obligations to protect the marine environment under the UNCLOS and related treaties

|

The Tribunal has jurisdiction over this question. |

| The legality of China’s activities on Mischief

Reef and their effects on the marine environment. |

Spratlys Group of Islands | Chinese construction activities are illegal | The Tribunal reserved its ruling on jurisdiction on this point for consideration in the Merits phase, as it would first require a determination as to whether the Reef is an island or a rock under the UNCLOS.

|

| The dispute on China’s law enforcement activities in the vicinity of Scarborough Shoal.

|

Scarborough Shoal area | These are illegal activities | To the extent that the

claimed rights and alleged interference occurred within the territorial sea of Scarborough Shoal, the Tribunal concludes that it has jurisdiction to address the matters raised in the Philippines’ Submission.

|

| The dispute concerning China’s activities in and around Second Thomas Shoal and China’s interaction with the Philippine military forces stationed on the Shoal.

|

Spratlys Group of Islands | These are illegal activities | The Tribunal considers the specifics of China’s activities in and

around Second Thomas Shoal and whether such activities are military in nature to be a matter best assessed in conjunction with the merits.

|

|

That China refrain from further interfering with Philippine activities or from carrying out its unlawful activities s

|

Both the Spratlys Group of Islands and Scarborough Shoal | China is obligated under UNCLOS to cease and desist | The Tribunal considers the specifics of China’s activities ion this point

to be a matter best assessed in conjunction with the merits.

|

| Mischief Reef, Subi Reef and Second Thomas Shoal | Spratlys Group of Islands | These are submerged features not above sea level at high tide, not islands under the Convention but China has illegally occupied them and constructed structures on them.

Moreover, Mischief Reef and Second Thomas Shoal are part of the exclusive economic zone and continental shelf of the Philippines;

|

The Tribunal reserved its ruling on jurisdiction on this point for consideration in the Merits phase, because of potential overlapping maritime entitlement claims with China (the presence of which would entail a delimitation of boundaries, a process outside the Tribunal’s jurisdiction).

|

| Scarborough Shoal | Off the coast of Zambales | Are submerged features like the above, but have protrusions that remain above the waters even at high tide, qualifying them as rocks that generate no more than a territorial sea and no entitlement to an exclusive economic zone or continental shelf;

|

The Tribunal found that it has jurisdiction to hear the Philippines’ claim over the features, of the shoal there being no potential overlapping claims with China or any other state.

|

| Johnson Reef, Cuarteron Reef and Fiery Cross Reef | Spratlys Group of Islands | Are submerged features like the above, but have protrusions that remain above the waters even at high tide, qualifying them as rocks that generate no more than a territorial sea and no entitlement to an exclusive economic zone or continental shelf

|

The Tribunal found that it has jurisdiction to hear the Philippines’ claim over these features, there being no potential overlapping claims with China or any other state. |

| Gaven Reef and McKennan Reef (including Hughes Reef)

|

Spratlys Group of Islands | Are low-tide elevations that do not generate entitlement to a territorial sea, exclusive economic zone or continental shelf, but their low-water line may be used to determine the baseline from which the breadth of the territorial sea of Namyit and Sin Cowe, respectively, is measured;

|

The PCA reserved its ruling on jurisdiction on this point for consideration in the Merits phase, because of potential overlapping maritime entitlement claims with China (the presence of which h would entail a delimitation of boundaries, a process outside the Tribunal’s jurisdiction).

|

How will the tribunal likely decide?

Many observers have opined that the Tribunal’s ruling in the merits phase would go the way of the Philippines.

Yet it would be more likely that the Tribunal will not declare the Nine-Dash Line illegal.

The most contentious issue at the moment is that of the Itu Aba, a feature located within the Spratly Islands. This was a sore point within the Philippine delegation, as Justice Antonio Carpi o has insisted that this be included in the Philippine claims, saying that it is too small to be an island.

The then Solicitor General, Francis Jardeleza (now also an Associate Justice of the Supreme Court) and who nurtured the Philippine claim until it was filed with the ITLOS, disagreed, saying that it is in fact the largest of the features and is clearly able to sustain human life, with a source of fresh water and a population (it is under the control of Taiwan).

The Itu Aba is believed by many experts to remain above sea level at high tide and contain enough fresh water to sustain human life, which would qualify it as an island in the view of international law.

If the PCA declares the Itu Aba to be an island, both the Philippines and China would then be in a situation where the sovereignty over that island would first have to be resolved as a condition precedent to declaring the Nine-Dash Line illegal. Remember that the Philippines adheres to the One-China policy, which then requires it to recognize the feature as part and parcel of the Chinese claim.

If the island does indeed belong to China, then China would be entitled to a 200-mile EEZ opposite Palawan. This would not only seem to justify China’s actions; it would also complicate the issue by creating an overlap of EEZs among states which would require delimitation – something China has reserved from UNCLOS dispute settlement procedures consistent with the treaty.

If Itu Aba or any other feature is indeed declared an island, then the Tribunal may accept the Chinese position. The lawfulness of the Nine-Dash Line could be viewed as a “mixed claim” that involves resolving an issue of territorial sovereignty – something beyond the jurisdiction of a dispute settlement under the UNCLOS.

The Tribunal will likely declare the other features as low-tide elevations not entitled to maritime zones.

As a matter of fact, many of the features within the West Philippine Sea are not islands able to sustain human life. Thus, the Tribunal will declare them simply as low-tide elevations. However, this being the case, so long as one feature, such as the Itu Aba, is declared an island, such would prove to be difficult for the Philippines to achieving its ultimate goal of declaring the Nine-Dash Line unlawful.

The Tribunal’s decision regarding China’s activities in the West Philippine Sea will depend on its ruling on the Nine-Dash Line issue.

Should the Tribunal decide that it cannot declare the Nine-Dash Line unlawful for lack of jurisdiction, it would follow that the Tribunal will not rule on the acts of China towards the Philippine fishermen. This is because the rights of both parties within the waters would remain undecided until the issue of sovereignty is resolved.

How should the Philippine government react to such a decision?

If the Tribunal should refuse to declare the Nine-Dash Line unlawful (either on the merits or due to lack of jurisdiction), the Philippines would be left with no other choice but to reengage in diplomatic relations. By negotiating with China peacefully, the Philippines could seek for compromises in protecting the rights and welfare of Philippine fishermen.

Should the Philippines seek to claim sovereignty over the features within the West Philippine Sea, it may certainly do so, subject to China’s willingness to enter into another arbitration for that purpose. But the chances of that are almost non-existent, in light of China’s previous behavior.

Moreover, even if the Tribunal should declare the Nine-Dash Line unlawful, the Philippines should still improve its diplomatic relations with China to encourage the latter to respect the ruling.

Unlike in domestic proceedings where the State may use police power to execute judgments, no such effective power exists under international law. Compliance with rulings of international tribunals and arbiters relies heavily on international comity and respect for international law.

International law, being founded for the most part on the consent of states, has been traditionally critiqued as ineffective and not “real law” because of the absence of a centralized enforcement mechanism one usually sees in the domestic level.

It has been argued that China, a country straining hard to acquire leadership status among the nations, cannot really afford a brazen disregard of international rules to which it has itself signed on. Thus, even if at the beginning, it refuses to abide by a ruling favorable to the Philippines, in the long run, it will have to reckon with it, as going against it will affect its trade and diplomatic relation with other countries.

But any ruling on the Nine-Dash Line claim will not by itself resolve all the territorial disputes in the South China Sea, inasmuch as it will only pertain to the maritime reaches of the Chinese claim.

It has to be remembered that the UNCLOS only applies to maritime regimes, but not to conflicts involving islands. The latter conflicts will have to refer to general international law, which involve the question of who has better title to a particular island or land territory based on effective occupation.

Still, an arbitral ruling on China’s claims to alleged islands and rocks that are under water, as well as the issue of which state may have sovereign rights on the waters surrounding then, will make the resolution of the entirety of the territorial conflicts in the South China Sea a little less complicated.

Download PDF copy of the primer.