From the 2013 UP Asian Center Primer on the West Philippine Sea

Five years after the 2016 South China Sea Arbitral Award, there is renewed debate about how best to understand its impact on the Philippine claims to the Spratly Islands chain. A contentious point is the Arbitral Award’s effect on Presidential Decree 1596, issued by President Ferdinand Marcos in 1978.Recent government pronouncements on the Julian Felipe Reef question have staked continuing Philippine claim over the feature based on the Marcos decree.

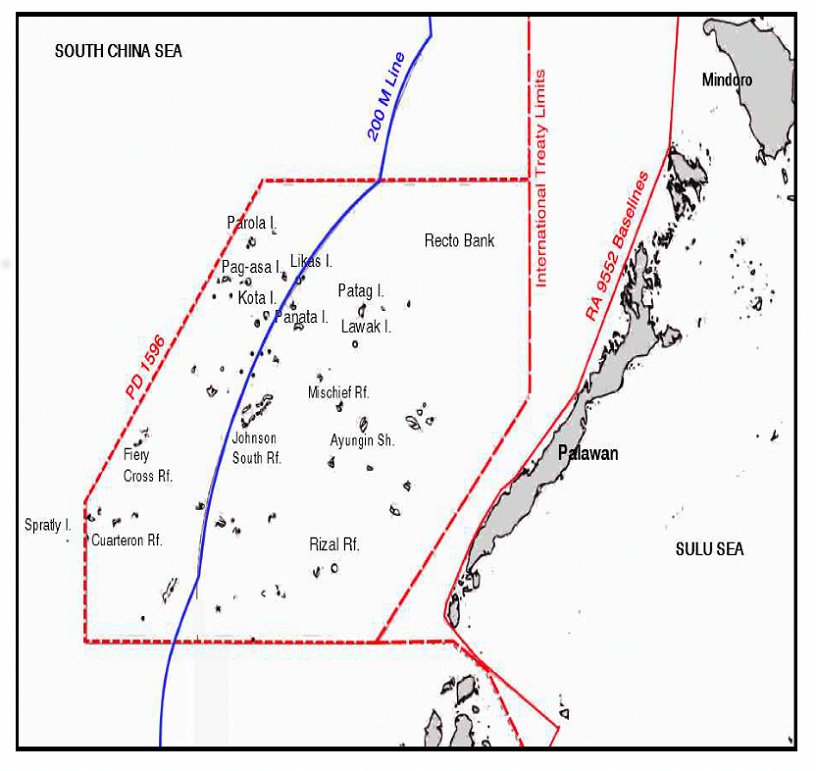

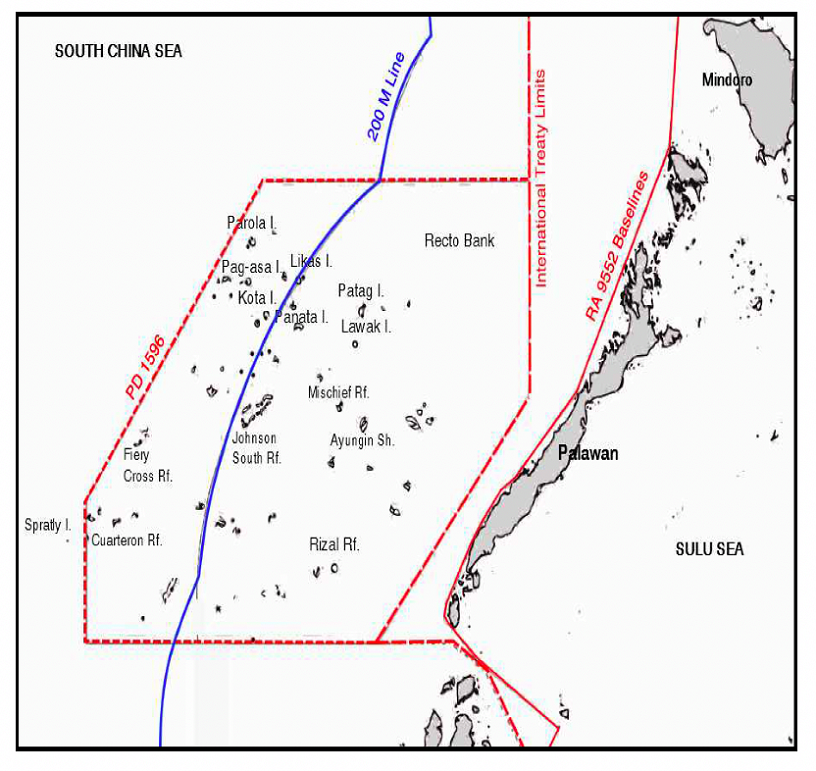

The decree had enclosed the Philippine claim in that part of the expanse of the Spratly Islands in the South China Sea through the medium of straight lines, named the enclosure the Kalayaan Island Group (KIG), and declared it Philippine territory. All islands and maritime features regardless of their nature, breadth, and dimension within the irregular polygonal area, meaning the entire block consisting of islands, islets, reefs, seabed, subsoil, continental margin, and airspace, are included in the KIG territory of the Philippines.

The decree did not mention any connecting and surrounding waters between and around the islands, islets, and reefs and the waters above the continental margin within the enclosure. Neither did it give an explanation as to the exact nature of the straight lines. One interpretation suggests that the Philippines considers these waters as maritime territorial waters and the straight lines as territorial boundary lines. This stems from the treatment accorded by the Philippines to the waters within the lines of the 1898 Treaty of Paris (Dzurek, 1996). The Philippines has since maintained the strategic ambiguity on the nature of the straight lines in PD 1596.

Section 2 of Republic Act 9522 (2009) placed the KIG under the Regime of Islands for purposes of the determination of its baselines in conformity with Article 121 of the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea. There is no express repeal or amendment with respect to PD 1596 and its lines of enclosure.

The 12 July 2016 arbitral award in the South China Sea Arbitration found that both China and the Philippines cannot use straight lines as a way of approximating archipelagic baselines in enclosing a mid-ocean archipelago like the Spratly Islands and claiming maritime entitlements seaward from the line. The arbitral tribunal found that the high-tide land features in the Spratly Islands are not regular islands but rocks. As rocks, they are entitled only to a territorial sea, but not exclusive economic zone and continental shelf.

The consequences of these findings are far-reaching not only for China but also for the Philippines. The nine-dash line claim of China was invalidated, but the limits of the Philippine sovereignty and territory in the KIG cannot now extend beyond 12 nautical miles seaward from the baselines of every rock capable of generating the maritime entitlement of a territorial sea.

What now then is the status of the straight lines in PD 1596? Have they been erased and reduced to irrelevance? The lines are still there, but no longer in their original state as territorial boundary lines of a monolithic Philippine territory, if such was the unarticulated understanding of the Philippines. They have assumed a different nature because recent developments materially changed and clarified their ambiguous circumstance. The Philippines can continue exercising sovereignty over every high-tide rock up to the outer limits of the relevant territorial sea in the KIG, but it cannot expand its territorial claim beyond the straight lines of PD 1596. The lines are relics of the past whose consequences continue to bind the Philippines just as it is bound by the new developments of international law such as the 12 July 2016 arbitral award in the case involving the Philippines and China.

*The author is finishing a doctoral dissertation on the notion of an Air Defense Identification Zone (ADIZ) in international law at the Hong Kong University Faculty of Law, where he had also earned an LLM in human rights law.