SEOUL – Malaysian political cartoonist Zulkiflee Anwar Ulhaque, who goes by the pen name “Zunar,” is perhaps his country’s most famous repeat offender.

Five times since 2010, Zunar walked in and out of jail for possessing a sharp, dangerous sense of humor showcased in sketches that poked fun at the extravagant excesses of former minister Najib Razak’s corrupt regime—prompting authorities to raid his office, confiscate his cartoon, and slap him with 43 years in jail, nine counts of sedition and a travel ban.

Award-winning Malaysian political cartoonist Zunar, who faced nine sedition charges for lampooning a corrupt regime, shares how he used laughter as a powerful form of protest during the largest gathering of investigative journalists in Asia. (Photo from the Global Investigative Journalism Network)

But what he calls a “jail-friendly job” did not stop him from fighting back through art and humor, hoping he and Razak would trade places someday.

“If I fight, I get two chances: whether I’m the one who will spend time in jail or the prime minister of Malaysia is the one who will spend time in jail,” the award-winning cartoonist told 440 journalists from 48 countries Oct. 6 in Seoul, South Korea, host of

‘Uncovering Asia 2018, the Third Asian Investigative Journalism Conference.’

Last May, the two famous Malaysians did trade places. Razak and his luxury-loving wife, Rosmah Mansor, were banned from leaving Malaysia, following one of the biggest corruption scandals in history involving a state investment fund, where billions of dollars were allegedly embezzled in luxury condominiums, private yachts and collections of bags and jewelry.

Zunar’s charges were dropped, and Malaysia’s anti-fake news law, the first in Southeast Asia and which Razak had pushed, was repealed.

Amid signs of a positive shift toward press freedom in Malaysia, it still figures at the bottom third of the world’s press freedom rankings, as with all Southeast Asian countries, where journalists are continually under grave threat. In Myanmar, a court has sentenced two Reuters journalists to seven years in prison for violating a state secrets act. In the Philippines, journalists are being murdered for their work.

Around the region, journalists are being harassed, intimidated and discredited, leading to an erosion of public trust and collectively raising the stakes for truthful and fearless reporting.

New threats

“We are in a landscape that is still a landscape full of landmines, that is filled with many new threats, with many new forms of harassment we are only now trying to understand and come into terms with,” veteran journalist Sheila Coronel, academic dean of Columbia Journalism School, said at the four-day Conference, which had for its theme, “Dealing with the New Threats.”

What used to be a broad consensus that the media plays an important role as watchdog of society is now “rapidly fraying,” Coronel said, adding that in many countries, journalists have either been “vilified as presstitutes” and purveyors of fake news.

Asian journalists urge the Myanmar government to free Reuters reporters Wa Lone and Kyaw Soe Oo, who were unjustly jailed for “doing their crime of exemplary reporting” on the Rohingya mass killings. (Photo from the Global Investigative Journalism Network)

The latest Pulse Asia survey released Oct. 10 showed 88 percent Filipinos are aware of the proliferation of fake news on social media, 79 percent of whom believe fake news is widespread.

Meanwhile, half of Filipinos who are on social media said they have changed their political views at least once because of something they had seen, read and/or listened to, the survey showed.

In September, Reporters Without Borders expressed alarm over the “increase in online harassment of a new kind of investigative journalists, those who verify the accuracy of social network posts” or fact-checkers.

Craig Silverman, who debunks fake news for BuzzFeed News, pointed out that in some cases, social media posts are used as strategies to keep the people’s attention away from things that might be inconvenient for the government.

He added that access to more information has contributed to the falling trust levels on the media and other institutions, partly because people now see how the institutions are flawed.

“When people do not have much faith in institutions,” he said, “they latch on to things that appeal to bias, things that give comfort because they are in line with popular belief, especially when it comes from a friend or family group.”

Fake news

Fake news is a term now loosely thrown around, which many leaders use to describe news they don’t agree with, or information that is critical to their governments.

VERA Files, which flags fake news that trends online, defines it as falsified information disguised as news used to deliberately deceive the audience and advance political, ideological, social or economic interest.

No less than President Rodrigo Duterte has accused the media of being behind fake news, although he has on more than one occasion shared fake information in public.

In January, Duterte called social news network Rappler a “fake news outlet” months after he falsely claimed several times that it was owned by Americans.

Journalists have been at the receiving end of Duterte’s ire even before he became president. He once dared journalists to “kill journalism, stop journalism in the country” and warned of “attacking” those who slam him by “making a research of their life and the life of their children.”

In his book, he said, there are three kinds of journalists: the crusaders, the mouthpieces of vested interests, and the lowlifes of the profession–or those that get killed because of engaging in extortion activities.

“The Constitution can no longer help you kapag binaboy mo ang isang tao (when you ruin one’s reputation),” Duterte told journalists on one occasion.

Steven Gan, editor of independent news organization Malaysiakini, which published Zunar’s second book “One Funny Malaysia,” says the role of the journalist is being maligned like never before.

He said media companies for the longest time have been under threat but not so much journalism itself. “I believe that the role of journalism … in recording events, in building opinions, in presenting facts is here to stay,” Gan said.

“But our work, looking at the way journalism has been attacked today, I’m not so sure anymore,” he added.

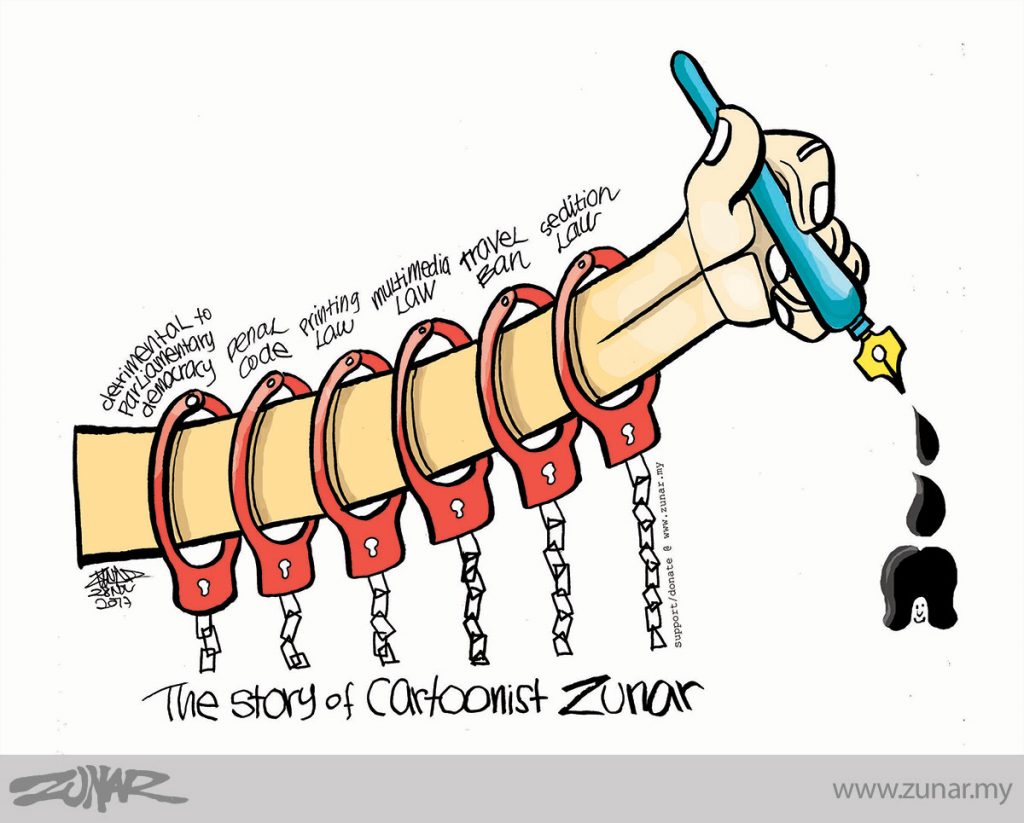

Zunar’s caricature on the six laws and policies hurled against him (Photo from Zunar’s official website)

In the face of sustained attacks to press freedom, Zunar’s fight may serve as reminder of why journalists should continue fighting back.

“By being neutral, you are giving mandate to the crooks to rule you even more,” Zunar said, urging journalists to expose corrupt governments.

In May, authorities seized 400 necklaces, 567 handbags, 423 watches, 2,200 rings, 1,600 brooches and 14 tiaras from Razak and Mansor’s home, and they are now caught in the middle of corruption and money laundering investigations around the world and facing the possibility of jail.

“I am a cartoonist, I draw cartoons. You are journalists, you write. Freedom of expression is our fundamental right, no government will give it to you (freely), so we need to keep fighting,” Zunar said.