By MALTE E. KOLLENBERG

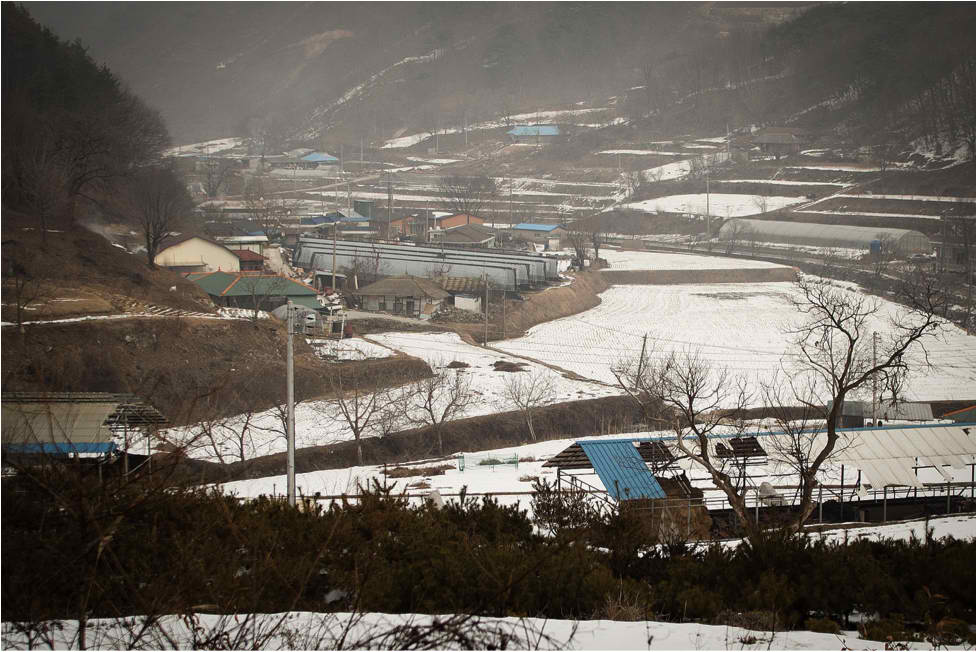

GONGJU, South Korea —Two and a half hours south of Seoul by land lies the farming village of Tapgok-ri, a remote part of the city of Gongju. Here, in the middle of nowhere, is where Cathy Deocades lived. It is nothing like the glittery and glamorous world shown in Korean dramas and K-Pop music videos, which are increasingly popular among Filipino women.

Gongju is no Seoul, Busan or Daegu. The houses here are small; hardly any building is higher than two floors. Encircled by mountains, the village is blanketed in snow in winter—and becomes gloomy and depressing—when the temperature drops to far below zero. Beside a cold wind blowing and the occasional dog barking, there is only stillness.

Here on Jan. 11, 2011, Cathy Deocades, 24, was found hanging from a wooden bar in an abandoned house several meters from her home. The police came and concluded suicide. Investigations stopped and the case was closed.

Cathy’s family in the Philippines could not believe a devout Catholic like her would take her own life. Her parents and siblings say she was living a difficult life in a place where she couldn’t speak the language, where she didn’t know the people and where she has been a victim of domestic abuse by her husband and mother-in-law.

But proving these allegations is difficult, even as the findings in the Philippines contradict the Korean certificate of death. Korean authorities did not order an autopsy; in Korea where suicide is common, autopsies are not.

Eight days after her death, Cathy’s body arrived in General Santos City in Mindanao. Her remains, along with the English translation of the Korean death certificate finding suicide as the cause of death, were turned over to Antonietta Odi, medico-legal officer of the City Integrated Health Services Office in General Santos, Cathy’s hometown.

Odi concluded the rope marks on Cathy’s body did not result from hanging. Her finding: “Ligature mark, abraded and contused, 36.0cms., with width ranging from 0.5 cm. to 1.0 cm., neck, anteriorly above the thyroid cartilage, oriented horizontally with almost uniform depth throughout its course.”

The “cause of death,” Odi wrote, is “asphyxia by ligature strangulation.”

According to the website forensicpathologyonline.com, “strangulation is that form of asphyxia which is caused from constriction of the neck by ligature without suspending the body. Pulling a U-shaped ligature against the front and sides of the neck while standing at the back can cause death.”

In short, Odi basically wrote that Cathy did not kill herself. Which also means it must have been a homicide.

Chung Nak-eun, director at the National Forensic Service (NFS) of Korea in Seoul, insists, though, that Odi’s autopsy report is wrong. “I know the case since February 2011,” he said.

On Feb. 28, 2011, the Gongju police asked the NFS to investigate Cathy’s case, after doubts were raised in the Philippines about the circumstances of her death. The NFS report, which reaffirmed that Cathy’s death was a suicide, was issued on March 11.

Chung was then the director of the central district office in Daejon and basically in charge of a possible autopsy, if the prosecutor had demanded one. But no autopsy was ordered.

“That was a big mistake,” Chung repeatedly said as he was explaining the case.

Gongju Prosecutor in charge Ko Ah-ra declined to comment on why no autopsy was carried out.

Yoo Young-kyu, a staff reporter of the Seoul Shinmun who has published extensively on unresolved murder cases, said, however, the real problem is that autopsies are not mandatory in suicide cases in South Korea.

In South Korea, if there is reasonable doubt about the death of a person, the prosecutor orders an autopsy. In Gongju on Jan. 11, 2011, the police found a broken clay pot and surmised that Cathy clambered on to this pot and then kicked it away, hanging herself using the rope from a hoodie sweater.

“There was absolutely no proof that someone else was involved,” said Ham Woo-suck of the crime scene investigation team of the Gongju police.

Dr. Hwang Kyu-yeop of Hyundai Hospital in Gongju city examined Cathy’s body and issued the death certificate, which states suicide as cause of death. In what appears to be a translation error, the English version of the death certificate lists “accident” in the space that asks for “kind of death.”

Hwang, who certified Cathy’s death, said it could not be ascertained if it was a suicide if no autopsy was undertaken. Over the phone in December 2011, he denied writing “suicide” as the cause of death. “I did not tell that to the police,” he said. “I said I don’t know how she died.”

In a later interview for this story at the Hyundai Hospital in Gongju, Hwang explained the procedure when certifying a death. A doctor fills out a form and answers questions about the death by ticking one of several options. And from what he saw on Cathy’s body, he said, nothing he saw spoke of homicide. Everything pointed toward a suicide.

For the reinvestigation, Chung of the NFS used pictures taken after Cathy was found. The ligature marks are clearly V-shaped, he said. When a person dies of hanging, the rope marks on the neck usually form a V. That just means that the rope goes up toward the ceiling and leaves marks on the skin shaped like a V.

Hwang of Hyundai Hospital confirms that. Cathy’s body clearly shows the marks of a case of “unusual hanging” as it is called among forensic experts. The rope does not go up on the back of her head. It left aberrations on the left side of her chin. “It was a suicide. We (the NFS) think the doctor in the Philippines did not describe the ligature mark correctly,” said Chung.

To be scientifically precise, there is also a theoretical chance that a person did not die of hanging but has been poisoned or drugged, he admits. To exclude these factors, an autopsy is needed that goes beyond the one done in the Philippines, said Chung. The statement had also been made by the doctor signing Cathy’s certificate of death.

“Regardless, it was a big mistake the prosecutor did not order an autopsy here in Korea,” Chung said.

Odi would not comment on the allegations made by Chung as well as her own autopsy report despite repeated phone calls, messaging and faxing for more than six weeks. On the rare occasions she talked on the phone, the medico-legal would only say she would give a comment soon.

Despite the reinvestigation by the NFS, Cathy’s family in the Philippines still doubts the official version of her death. Philippine embassy public interest lawyer So Ra-mi had represented the family in South Korea. Last Dec. 21, she assumed the case would be closed the next few days as the reinvestigation has not led to new discoveries.

Indeed, on Dec. 26, 2011, Prosecutor Ko Ah-ra issued the final report: Case closed.

(To be concluded)

(The author is a German journalist based in Seoul and is a student at the Ateneo de Manila University’s M.A. Journalism Program and the Asian Center for Journalsim. He submitted a version of this story for his Investigative Reporting class under VERA Files trustee Luz Rimban.)