BANGKOK, Feb 24 (Reporting ASEAN) – If ASEAN issues were a consumer product for sale, buyers wouldn’t exactly be queuing up for it – not even with the sales pitch that it is a brand with 50 years of history to fall back on this year.

By ‘ASEAN’ here, I refer not just to the organization and the bureaucracy behind it, or the state-defined ASEAN, but the ASEAN that represents Southeast Asians who call themselves a ‘we’ unit of some sort, however loosely defined.

Yes, on the one hand, many media organizations do not find reason enough to invest more in ASEAN as a news beat, or an area of expertise where to train its journalists in. The nature of news production means that newsdesks often consider it ‘foreign news’ that ranks lower on the priority list – even if in many ways, it is Southeast Asia’s biggest running story. On the other hand, the ASEAN bureaucracy often sounds like it would be happy to stay under the radar of public focus.

These two divergent tendencies make for a mix of challenges that stand out even more during a year when ASEAN should be a subject of critical reportage by the media, whose audiences deserve to know what regional integration has in store for them. What can be done when one side – the media – are less than hopelessly attracted to ASEAN matters, and the other side – ASEAN itself – would rather be left to its quiet routine?

Critical analyses in the public space of ASEAN’s relevance makes for news, for very practical reasons that do not include a blind love for all things ASEAN.

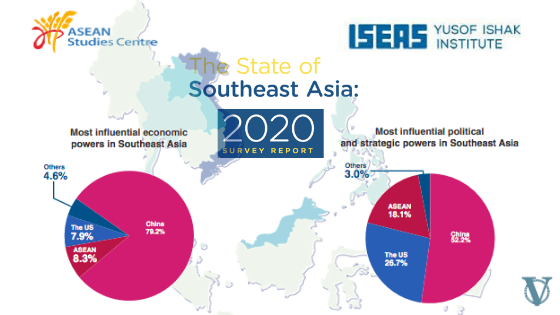

For all its flaws, ASEAN is the main grouping in this region – thriving, in fact, compared to those in South Asia or Africa. Something has made ASEAN tick, and its presence has been a bulwark of security in a region that saw conflict rage up to three decades ago.

ASEAN centrality has made ASEAN the venue for hosting the world’s most sustainable multilateral fora that draw world leaders regularly – the ASEAN Regional Forum, ASEAN’s talks with its dialogue partners, the ASEAN Defence Ministers’ Meeting-Plus, which includes China. These talkfests are safe spaces for discussion that are indispensable in diplomacy.

Bigger ASEAN footprint

After half a century, it has now taken on more by becoming an ASEAN Community, a process that will go on for decades. Indeed, pushing ASEAN as a “model of regionalism” is one of ASEAN’s six priorities this year, going by a Feb 21 statement (curiously labelled a press release) by the Philippines after the ASEAN foreign ministers’ retreat.

Beyond the feel-good phrases of ASEAN as a community of opportunities, the fact is that ASEAN as an inter-governmental organization owes it to the more than 600 million people in the region to deliver the goods, as it were, including in regional integration. Our taxpayers’ money also goes to ASEAN.

ASEAN’s looking to a new chapter of its life as a community these should open up more areas for news investigation, because governments have taken on commitments that are likely to impact on areas that range from national laws and policies, to economics, trade and investment, and overall human development.

The metamorphosis widens ASEAN news, which has traditionally come under the foreign affairs beat. Because the Community project covers politics, economics and socio-cultural aspects, the digging ground for stories now reaches just about every beat – an ASEAN story is a rights story, a labour story, a business story, a political story. These stories, by definition, go far beyond the airconditioned halls where decisions and communiqués are made and announced.

This change in ASEAN throws up questions to journalists: How can they effectively tell the story of integration, opportunities and challenges all, give it a human angle, and hold it up against governments’ commitments to better the lives of its people? What habits might newsrooms need to rethink, if media are to tell the public what they need to know about the impact and costs of regional integration?

Coverage of ASEAN integration may require creative, newsy and interesting transboundary coverage across beats, the deft linking of the national and the regional by writers and copy editors, the creation of space for original reporting on regional issues, the investment in journalists who can be challenged to study and specialise in regional affairs, and the building of skills in explanatory reporting versus just relaying what ASEAN states or officials said.

For too long, the definition of ASEAN news has been limited to its high-profile summits and editors did not see the need to have original news reports done by staff journalists, including from the perspective of citizens, not diplomats or states. ‘Just use the wires’ has been the common practice – but is this still enough given that the foreign and western wires naturally produce news for their own, mainly non-Southeast Asian, audiences? How do media in ASEAN take back a narrative that should be theirs to tell?

Interest in ASEAN typically peaks among journalists when their country is ASEAN chair, before it subsides. For many, this is the only time they cover ASEAN issues. Lucky are those whose news outlets allow them to specialise in regional issues, or have resources for overseas coverage.

Time to chip away at opaqueness

If the ASEAN Community’s arrival is widening the space where ASEAN affects its constituency’s lives, the scope that media gives to dissecting this – and keeping watch on the promised benefits of integration – needs to expand as well. A number of Asia and ASEAN-focused series, pages or television programmes exists and though many remain at the stage of introducing ASEAN countries to each other or sounding like travelogues, they are a start of defining ASEAN as a beat.

At the same time, ASEAN’s growing footprint should get member states to see and accept that deeper engagement with the public is not only a natural part of community-building and maturity, but also for their own stake in the ASEAN Community project.

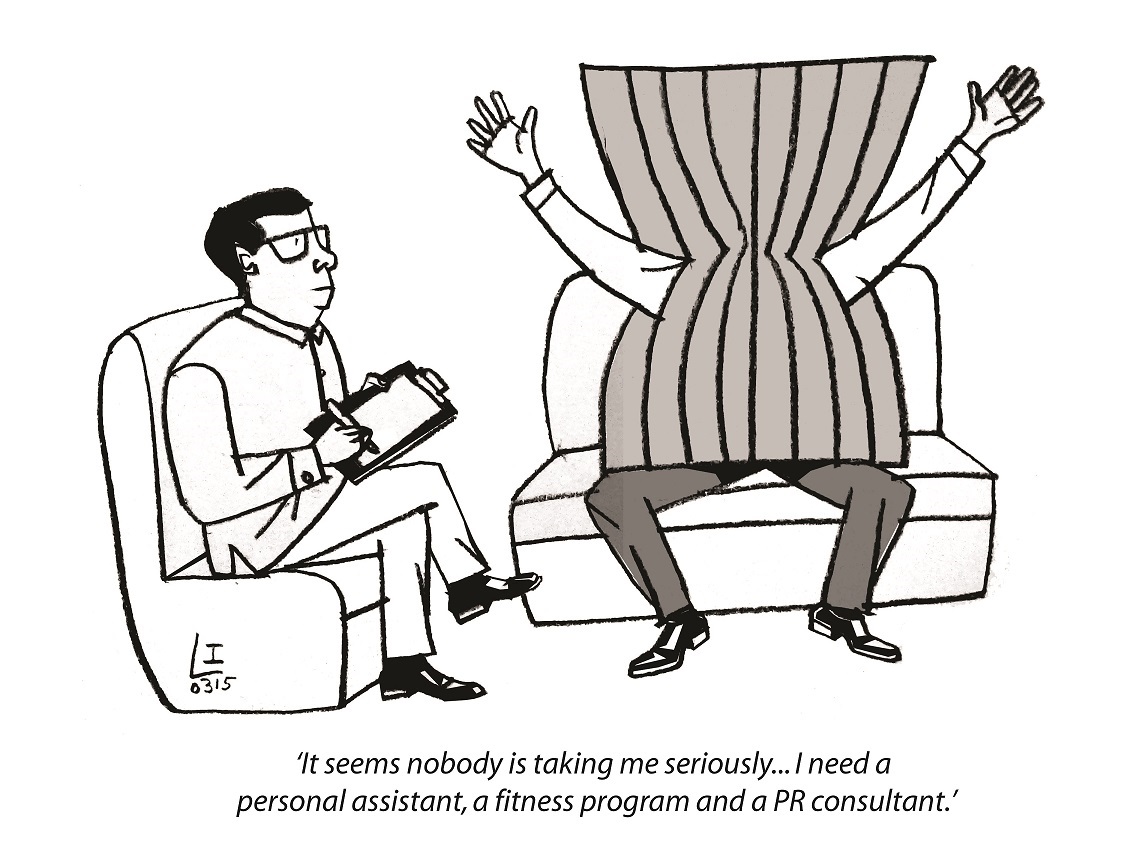

A more relaxed manner of dealing with the media is far from second nature for ASEAN, where the position of secretary-general was not designed to be a strong one, and one where there is, by design, no single official spokesperson. Announcements by the ASEAN chair do not always allow for questions to be asked after they are read. Add to that the fact many a journalist has found ASEAN’s press material uninteresting.

At the Reporting ASEAN media forum in Bangkok, Thailand in February, ASEAN Deputy Secretary-General AKP Mochtan asked journalists to “convey stories about ASEAN rather than only news”, referring to the need for reportage beyond headline-making stories such as the South China Sea disputes, which do not equal ASEAN. He added that coverage of ASEAN is “like a marathon without a finish line”.

No media norm

But ASEAN needs to remember that encouraging journalists to cover ASEAN issues more does not mean trying to control what they report, but involves providing an environment that allows the media to do their job.

This is not a norm in ASEAN at present. ASEAN cannot be more than its member states, including in the area of media environments. There is no consensus on how ASEAN countries look at the media : A good number of countries do not allow space for free media, censor reports that could be seen to be ‘hostile’ to other member states, or see the media as a bullhorn for the state.

Against this backdrop, ideas of setting up an ASEAN news outlet that come up once in a while under the predictable tag of ‘cooperation’, are at best on a slippery slope. In an ASEAN where many governments do not subscribe to the media playing a check-and-balance role to government, this does not exactly promise a raft of independent, interesting, incisive reports. In some ways, it brings back memories of those days decades ago, when less than democratic governments, including in Asia, favored ‘development news’ (and gave it a bad name) and tried to set up news agencies for these.

In 2017, news organizations need to find their own way of stepping up from under-reporting and skimming over ASEAN issues and invest in covering the regionalization process because they find and set an editorial imperative for it.

Tough reminder from Brexit

There is a political imperative as well to taking a closer look at ASEAN, as the world sees the signs of unpopularity of multilateralism and regionalization, which involve a balance between national and regional sovereignty. While the European Union and ASEAN are very different integration models, Brexit is a reminder that perception is reality. States need to ensure that they convey the dividends of regional integration well and that the media have the environment to assess this with a critical lens.

As it is, there is in many ASEAN countries, a perception that the ‘freer movement’ of some workers in the ASEAN Economic Community would open the floodgates to all other nationals and lead to the wholesale loss of jobs – even if this is farthest from fact. Freer mobility for skilled professionals applies to one percent of the region’s labor force, but fact can lose out to, well, fear.

“ASEAN has to get people on board if it is to become a community,” said Jakkrit Srivali, outgoing director-general for the ASEAN department at the Thai foreign ministry. “What’s important is to ensure a buy-in by its public.”

Johanna Son, who has followed regional issues for over two decades, is editor/founder of the Reporting ASEAN media program, hosted by the Probe Media Foundation Inc.