By YVONNE T. CHUA

WHAT could possibly go wrong in the automated national elections in May 2010?

WHAT could possibly go wrong in the automated national elections in May 2010?

Just because voting will be computerized does not mean it will be error- or problem-free, said Prof. Pablo Manalastas, a faculty member of the Ateneo de Manila University’s Computer Science Department and lecturer at the University of the Philippines.

Manaslatas laid out the possible scenarios: What if the two special felt-tip pens allotted per precinct dry up before voting ends and voters have nothing to write their choices with? What if the counting machine gets jammed while ballots are being fed to it? What if the local GPRS connection is bad and slows the transmission of the results from the precincts to the municipal or city canvassers? Or what if someone snatches the laptop computer at the canvassing center? (Listen to Manalastas explain his findings.)

But these scenarios aren’t as worrisome as what else could happen: The whole system could be rigged, and all computers—from those at the precincts all the way to those at the Commission on Elections and Congress that will canvass the results for the senatorial and presidential elections—could be pre-programmed to make certain candidates win.

How could this happen?

The Precinct Count Optical Scan (PCOS) machines could arrive at the precincts with prepared ballot images and election results already inputted into the system, and the computers for canvassing with prepared Certificates of Canvass (COC) and Statements of Votes (SOVs). And at any stage of the elections, someone who has the root password could log into the system from a remote site and control the canvassing computers—and the canvassers wouldn’t even know. This could happen as early as municipal canvassing because the computer will stay connected to the network for 24 to 72 hours via modem starting at 6 p.m. of election day.

Meet the automated version of “Garci,” the infamous Elections Commissioner Virgilio Garcillano whose manual operation of swapping genuine ERs, COCs and SOVs with the ones he and his “operators” prepared allegedly helped President Gloria Arroyo get her extra million votes in the 2004 elections. The whole operation was documented in leaked wiretapped phone conversations.

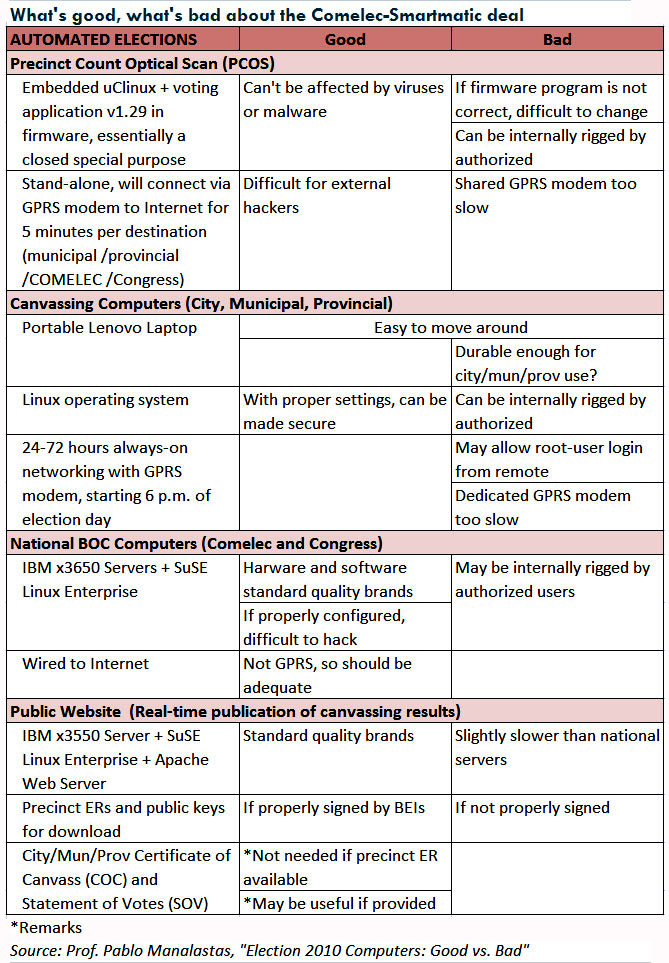

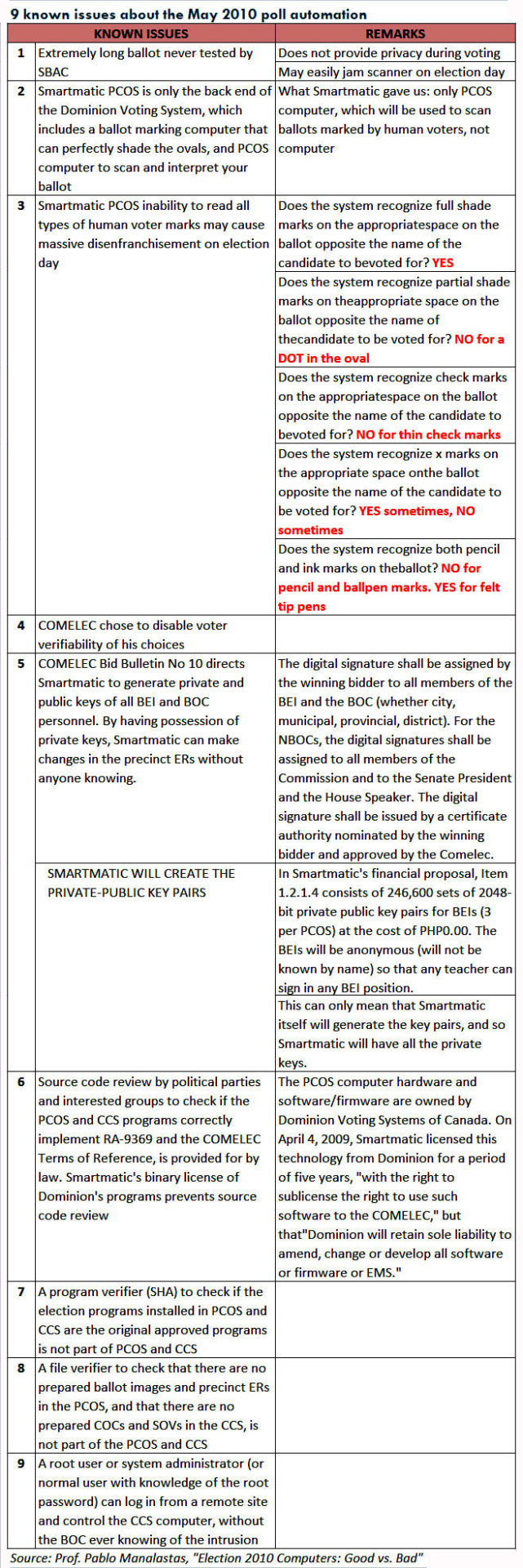

Despite automation, rigging next year’s elections is still possible because of flaws in the P7.2 billion deal between the Comelec and Smarmatic-TIM Corp., Manalastas said. (See the matrices“What’s good, what’s bad about Comelec-Smartmatic deal” and “9 known issues about the May 2010 automation.”)

The same fears of possible computerized cheating were voiced by the Concerned Citizens Movement, which has pointed out that Comelec failed to conduct a pilot testing of the PCOS machines, in violation of the poll automation law. The CCM has questioned the contract before the Supreme Court, saying the Comelec committed “grave abuse of discretion amounting to lack or excess of jurisdiction” when it awarded the contract to the Smartmatic-TIM.

The High Court heard oral arguments on the petition on July 29.

Manalastas depicted the different scenarios, including the worst-case, after analyzing the 21-page financial proposal Smartmatic-TIM submitted to the Comelec’s Special Bids and Awards Committee. And the problems, he said, partly have to do with the source code or the human-readable computer programming language.

Republic Act 9369 or the poll automation law allows political parties and interested groups to review the source code to check the PCOS and Consolidation/Canvassing System (CCS) programs.

Trouble is, the source code is still owned by Canada’s Dominion Voting Systems which, under its agreement with Smartmatic-TIM, “will retain sole liability to amend, change or develop all software or firmware or EMS (Election Management System),” Manalastas said.

The IT expert said the proposal also explicitly states that Smartmatic-TIM holds only a five-year “binary” license for the machine code, but not a “source” license that would allow the winning bidder to open the source code for review. The machine code is the only language a computer understands but is not human-readable like the source code.

To be fair, Manalastas found several “good” points in the contract between Comelec and Smartmatic-TIM. For one, the Linux operating system in the PCOS computers “can’t be affected by viruses or malware.” The CCS units, also fitted with Linux, “with proper settings can be made secure.”

Because the PCOS machines will be stand-alones during elections and will only be connected via modem when voting has ended, Manalastas said external hacking will be difficult.

He also said the servers to be used for canvassing by the National Board of Canvassers and for the public website that will publish the canvassing results real time are “standard quality brands.”

But Manalastas is bothered by the Comelec’s failure to test the 8.5-by-30-inch ballots that will be used in the elections. Smartmatic-TIM machines were fed only with A4 or 8.26-by-11.69-inch ballots during the testing done by the poll body.

The IT expert said the “extremely long” ballot may easily jam the scanner on election day aside from not providing privacy during voting.

Manalastas disclosed that Smartmatic-TIM is supplying the Comelec just the back end of Dominion’s voting system. The front end includes a computer that marks ballots and perfectly shades the ovals.

“What Smarmatic gave us (is) only (the) PCOS computer, which will be used to scan ballots by human voters, not computer,” he said.

As a result, Manalastas said he fears “massive disenfranchisement” on election day. The reason: The PCOS recognizes fully shaded marks on the oval opposite the candidate, but does not read a dot, thin check mark or other partial shade marks. It recognizes only felt tip pens or permanent markers, but not pencil and ballpen marks.

Under its financial proposal, Smartmatic-TIM will provide every precinct with only two permanent markers. There will be 80,000 precincts on election day, each with 1,000 voters.

Comelec required Smartmatic-TIM to generate 246,6000 pairs of private and public keys or digital signatures, a security feature, for all members of the Board of Election Inspectors and Board of Canvassers. The public keys will be issued to the election personel, but Smartmatic gets to keep the private keys.

“By having possession of private keys, Smartmatic can make changes in the precinct ERs without anyone knowing,” Manalastas warned.

He said Smartmatic or Comelec could prepare precinct ERs with the counts for every candidate and could sign these with the private keys a few days before election and leave these in the PCOS machines. “When they deliver to the precincts, tapos na ang eleksiyon (the election is over),” he said.

Manalastas further said the digital signatures are not secure because Smartmatic appears to have no intention of buying these from a certificate authority like VeriSign and will instead generate the key pairs by itself. Smartmatic-TIM’s financial proposal has no budget item for the keys, he said. Each pair would have cost $100.

He said it is better for the BEI member to generate his or her own private key and the corresponding public key and submit the public key to the Comelec for certification.

The IT consultant also revealed the lack of a program verifier and a file verifier in the PCOS and CCS.

The program verifier checks if the election programs installed in the computers are indeed the originally approved programs. The file verifier, on the other hand, checks if there are prepared ballot images, precinct ERs, COCs and SOVs.

Manalastas said the Comelec also chose to disable a feature in the PCOS that would allow the voter to verify his or her vote before casting it even when the poll automation law specifies voter verifiability of his or her choices.

The computer expert expressed concern that Smartmatic-TIM is providing only 2,200 backup PCOS units even after it acknowledged a breakdown rate of up to 10 percent of its machines. This means it should provide 8,000 backup units, he said.