Among young Kalingas, the practice of having traditional tattoos has declined ages ago. In contrast, local and international visitors have made the remote village of Buscayan, Kalinga a hot spot for getting a tattoo from Whang-ud, considered as the last and the oldest mambatok in Kalinga. It was a 2009 documentary Tattoo Hunters by American anthropologist Lars Krutak that made Whang-Ud well known. Recently, Vogue made Whang-ud, 106 years old, its oldest person ever as cover model.

Consequently, Butbut elders in Buscayan have coined a new tattoo process called emben a whatok or “invented tattoos” that use some parts of traditional tattoos for visitors, only for decorative purposes.

The lure of authenticity

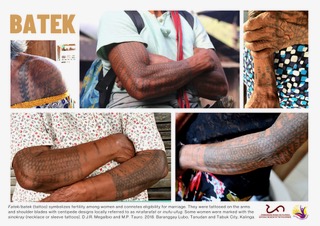

Batek or batok (“to hit” or “to strike”) is the term for the traditional tattoos of northern Luzon, after the “tek” sound of hitting the stick during tattooing. In Visayas and Mindanao, it is called patik, a term used for snake or lizard markings, or any design on the skin.

Both hand-tapping and hand-poking techniques are used in the country, traditional techniques also used by other indigenous groups in the Asia-Pacific region.

In hand-tapping, a “stick-with-a-thorn” (gisi) is made from carabao horn bent with fire, with steel needles attached at its tips. Using a light wooden stick (pat-ik), the gisi is tapped repeatedly, 90-120 taps a minute. In Buscalan, the gisi has a tiny hole at its end where a lemon thorn is inserted that pierces the skin, a method used by Whang-ud and the grandnieces she has trained to continue the tradition.

Black ink remains the preferred color that comes from the soot scraped from a clay or aluminum pot. Its blackness reminds elders of the color of the native pig used for payment in the past. The soot is mixed with water or plant dye, to get the desired thickness and consistency.

Social practice

In the Cordilleras, tattooing was practiced among the warriors of Bontoc, Ifugao, and Kalinga. Western ethnographers in the past unduly emphasized that headhunting and tattooing were synonymous with each other.

Analyn Salvador-Amores, PhD has noted that tattooing is part and parcel of Kalinga social practice, with a range of social meanings. She has done extensive research on traditional tattooing of the Cordilleras, especially among the Butbut tribe, a Kalinga ethnic group in Buscayan and the author of Tapping Ink, Tapping Identities: Tradition and Modernity in Contemporary Kalinga Society, 2013.

Chest tattoos (whiing) on men denotes bravery in defending the village against enemy attacks, notes Salvador-Amores. In fact, bravery as reflected in traditional tattoos, is never abstract; the degree or level of bravery is visually expressed.

Tattoos on warriors also serve as talismans to protect them from evil spirits or as an “armour” that protects their bodies.

Tattoos were and are indicative of the high social standing of the warrior class, as well as a marker of wealth and social status for both men and women.

A painful rite of passage, being tattooed among the Igorots signifies becoming a social person, and a full and responsible member of one’s community, says Salvador-Amores.

When a male becomes a respected warrior and tattooed, his female children and female first cousins were also tattooed. A tattooed woman is considered ready for marriage. Tattoos are believed to increase a woman’s fertility and a sign of virility for men.

Beyond physical beauty, tattoos represent inner strength and character that one carries to the grave and the afterlife. As Butbut elders say, it is only the batok that is buried with them, the only thing that they truly own and inherit from their ancestors.

Designs

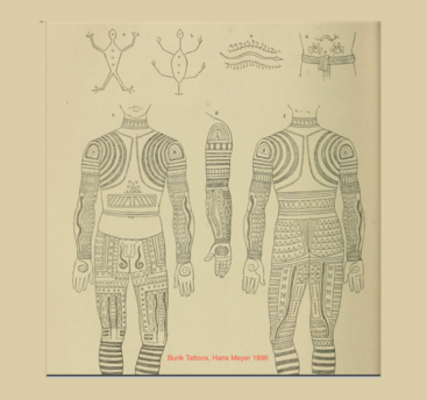

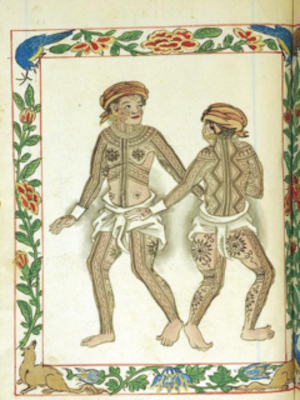

In general, traditional tattoos consisted of geometric (lines, circles, stripes, zigzags) and figurative (lizards, snakes, scorpions, plants) designs.

As badges of honor, such tattoos include binulibud (three parallel lines from the forearm to the biceps or triceps), biking (chest tattoo), gulot or pinupungol (stripe pattern), dakag (back tattoo), gayaman nan banas (centipede-eating lizard), bituwon (star) and sorag (moon) as light source.

Women are tattooed on the forearms, upper arms, and shoulder blades with centipede or fern design, or with sinokray, necklace tattoos. Married or pregnant women are tattooed with lin-lingao, x marks on the forehead, cheeks, and nose as protection against bad spirits.

Interestingly, the terms “art” or “artist” do not exist in the vocabulary of the Butbut, observes Salvador-Amores in a 2018 article. In other words, tattoos and tattooing are viewed “as a social practice and a cultural endeavor” integrated into the way of life itself.

History

Long before Spain’s arrival, tattooing was a common and widespread practice in the country. An early Chinese account, Summary Notices of the Barbarians of the Isles (1349) by Wang Ta-yüan, reports that natives from Sulu, Mindanao, and Manila waste their money getting tattooed from head to foot.

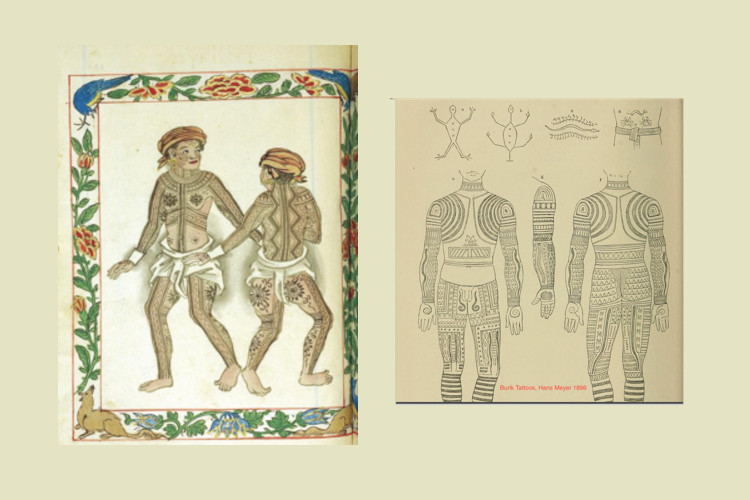

The Spaniards called the Visayans “Pintados” because they were “painted” or tattooed. The Boxer Codex (1590) portrays Visayan tattoos as “bold lines up legs and back, and matching floral designs on both pectorals and buttocks.”