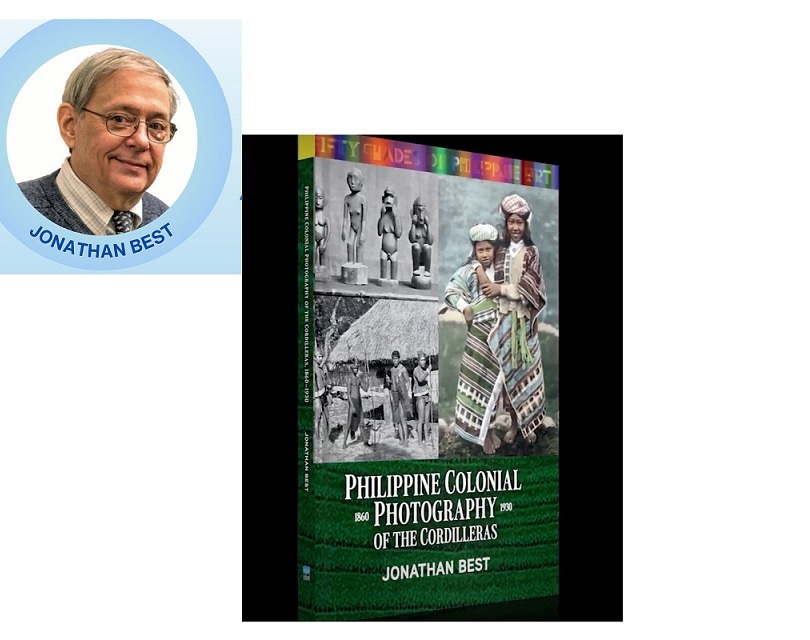

Jonathan Best offers a distinct visual approach into the rich culture and heritage of the peoples of the Cordilleras from 1860 to 1930 in his book, Philippine Colonial Photography of the Cordilleras (1860-1930). Quezon City: Vibal Foundation, Inc. 2023., 112 pp.

Using photographs as visual records is a way of understanding Cordillera history with a critical eye at the turn of the 20th century.

The seemingly automatic recording of an image by the photographic process has led to the popular (and erroneous) saying that “the camera does not lie.” One must recognize the inherent bias in the act of taking a picture.

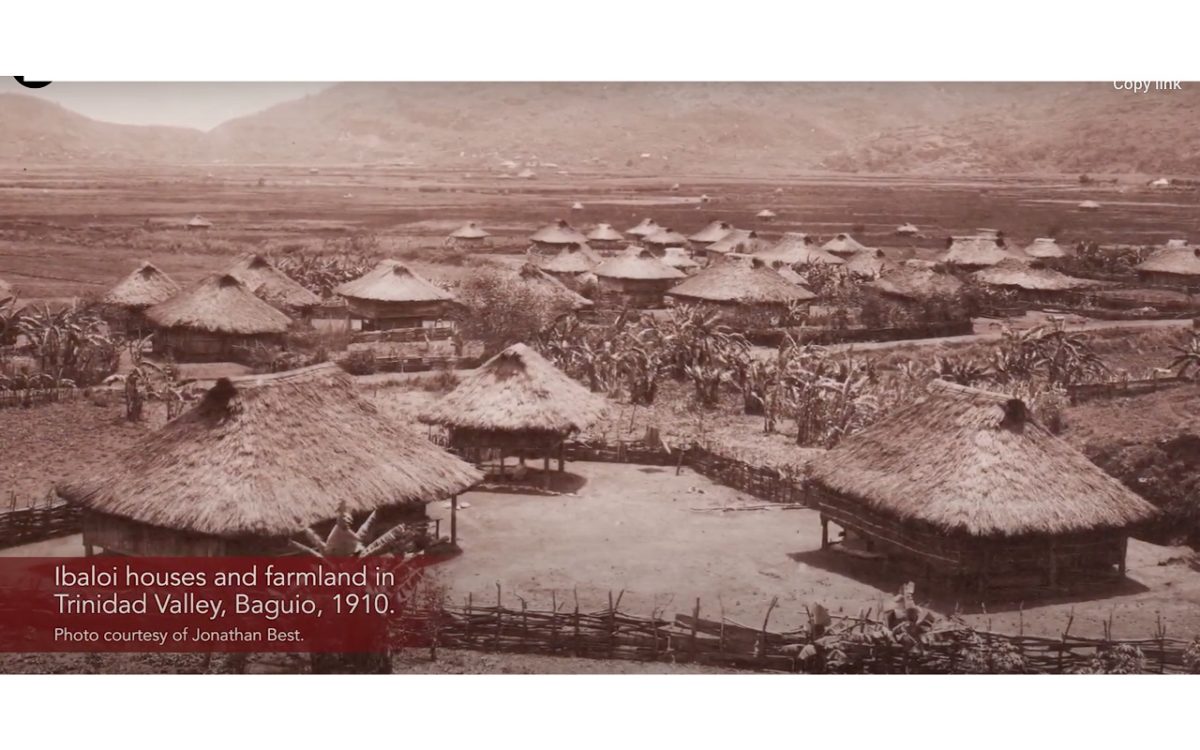

The peoples of the Cordilleras consist of major ethnolinguistic groups of the Kankanaey, Ibaloi, Bontok,Kalinga, Isneg, Ifugao, Kalanguya, Iwak, and Ga’dang.

The unwavering defense of their territory and traditional way of life have been the constant themes of Cordilleran history and struggle against Spain’s “the cross and the sword” and America’s “manifest destiny.”

Content

The first chapter gives an overview of the beginnings of photography in the country, focusing on the early European photographers who documented the peoples of the highlands, followed by the Americans, and other lowland Filipinos.

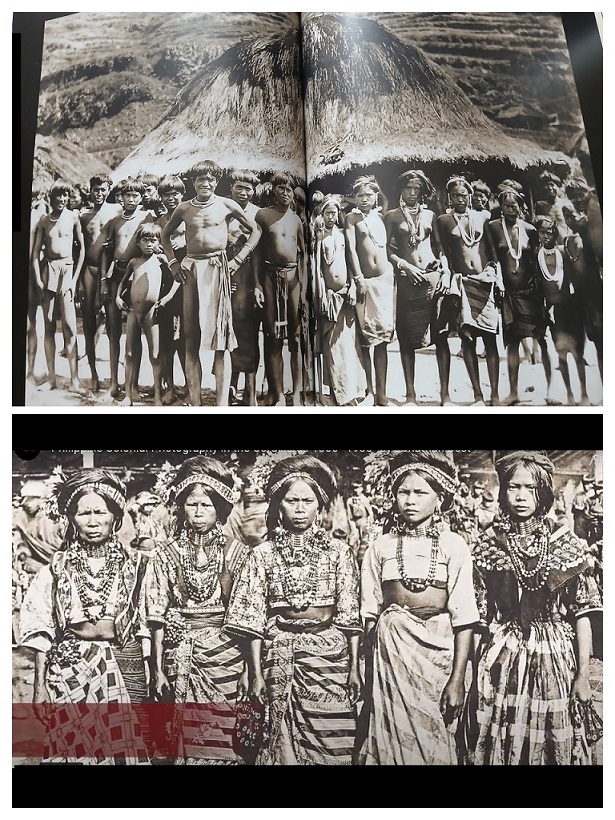

The second chapter details the relations between the indigenous population of the Cordilleras and the colonial American administration (1898-1946), as well as the work and influence of Dean Worcester, Charles Martin, Roy Franklin Barton, and others to present images of the “uncivilized” indigenous groups to the American public.

The third chapter presents the photographs themselves divided into “Artisanship and Craftmanship;” “Life in the Cordilleras;” and “Lens of the Past.”

Be humane

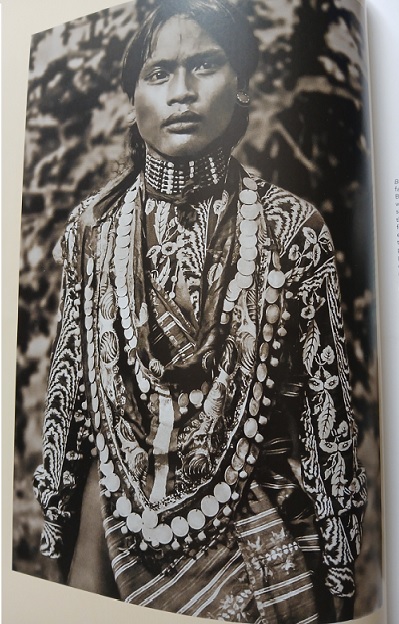

In the book’s preface, Jonathan Best says: “I have tried to present the ancestral peoples of the Cordilleras in a new, more positive light than they have often been depicted.”

He also hopes that the photographic legacy “…will inspire young Igorots–and all Filipinos–to preserve, explore, and be proud of their ethnic roots and their ancient ancestral heritage.”

Early Western photographers

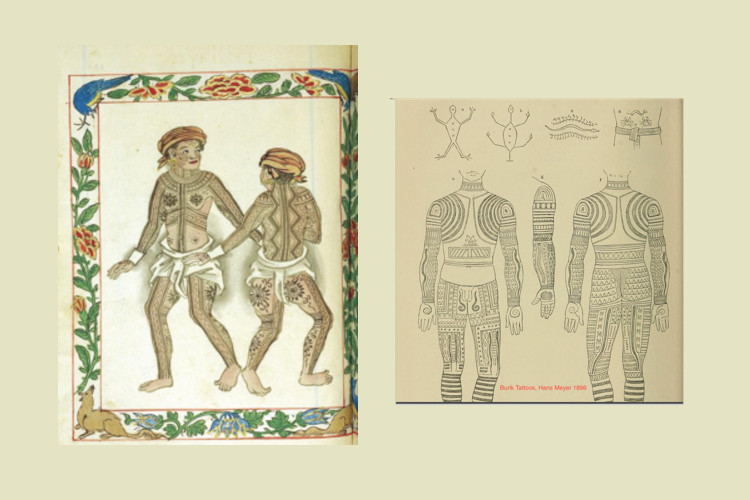

A few European photographers (Alexander Schadenberg (1851-1866); Hans Meyer (1858-1929), Feodor Jagor (1818-1900) ventured into the Cordilleras to photograph and document the Igorots in the late 19th century.

During the American colonial era, large numbers of Filipinos and foreigners started travelling and living among the native peoples in the Mountain Province and left a visual legacy of the Igorots used in this book. In its appendix, a short list of colonial-era photographers is included.

The earliest photographs of the Igorots were mostly those individuals who went down from the mountains and photographed in studios or outdoors from the late 1840s and onwards.

The highlanders are still referred as Igorots or Igorottes in Spanish, a term that simply means mountain people.

Visualizing cultures

The almost 200 photographs in this book were collected over 40 years in Europe, the United States, and the Philippines. The earliest ones came from the remnants of the H. Otley Beyer (1883-1966) archive after he died and sold to collectors.

Known as the father of Philippine anthropology, Beyer headed the first anthropology department at the University of the Philippines and wrote several books on Philippine ethnography.

Each group in the Cordilleras have their own traditions and unique style of clothing, ornamentation, and architecture. The extensive documentation of early Cordillera life in photographs remains invaluable primary sources of information, despite the biases of the original photographers.

In the section “Artisanship and Craftmanship,” material culture remains the focus with photographs of festive garments to daily clothes, ornamentation that range from Kalinga heirloom agate beads and braided bracelets; Gaddang earlobe plugs, heirloom bead headdress; Kalinga traditional hair pieces, heavy brass ornaments; Ifugao wooden rattan cap; Tingguian beads; Isneg festive costumes; Igorot woven baskets; and the ubiquitous tattoos.

Everyday life

The photographs capture the rhythm of everyday life more than a hundred years ago that had nurtured generations and remains embedded in ancestral memories: performing a war dance to a gangsa, or gongs, playing music, attending festivities, celebrating weddings, attending a funeral, the solemn gathering and meeting of elders in an ato, men and women in front of an olog communal hut, weaving cloth in backstrap looms, forming clay and making potteries, planting and harvesting rice, or daily tasks of carrying sacks of produce on the head.

Through vintage photographs, one can compare what material culture and rituals have changed, what have been lost forever, or what have remained.

That rhythm of life and work has continued to this day in the Cordilleras under its digital-age generation.

It would be interesting to see how smartphone cameras would have captured life in this area, a hundred years from now.

Jonathan Best

A serious collector of vintage Asian photography and ethnic art, Best’s books include Philippine Picture Postcards,1900-1920 (1994) and A Philippine Album: American-Era Photographs, 1900-1930. (1998).

With a degree in art history from Hofstra University, New York, Best is a writer, editor, and reviewer of articles and books on Philippine and Southeast Asian art and culture. He is also a senior consultant at the Ortigas Foundation Library.