KAAGI: Tracing Visayan Identities in Cultural Texts is an ongoing virtual exhibit, as part of the recently concluded 6th Annual Philippine Studies Conference by SOAS University of London, on Visayan identities. See https://kaagi.philippinestudies.uk/exhibition/

The root word ági means passage, trace, incident, to pass by, or to pass through.

The exhibit explores the colonial archives and cultural practices of the Visayan region that includes Panay, Negros, Cebu, Siquijor, Bohol, Leyte, and Samar.

Stripping fibers from a pineapple leaf.

Visayan culture

Ten categories of early contact cultural heritage are presented in an interactive portal through videos, documentaries, interviews, music, and performance art.

The categories are Salo (Food and Feasting), Kulon (Clay), Hablon (Textile), Puthaw (Iron), Banig (Reed Weaving), Kahoy (Wood) Lagang (Shell), Balak (Spoken Word and Ritual), Bulawan (Gold), and Pinta (Working with Pigment).

They all interconnect with the daily lives of the Visayans, from the basic need of food, shelter, and clothing to sources of livelihood, status and prestige, as well as belief and spirituality.

They are based on word entries found in a 17th century Visayan-Spanish dictionary (Vocabulario de la Lengua Bisaya, Hiligueina y Haraya de la Isla de Panay y Sugbu y Para Las Demas Islas, ca. 1628) by Alonso de Mentrida (1559-1637), an Augustinian friar.

Moreover, the exhibit traces Visayan heritage through the art and practice of contemporary Filipino artists who “adapt, transform, and subvert these representations.”

Paraglara, the women mat weavers of Basey, Samar.

Panay weavers

A documentary titled Threaded Traditions: Textiles of Panay by Luna Mendoza, presents Panay weavers with their patadyong, hablon, and piña cloth.

Making piña cloth is tedious and starts with planting Spanish red pineapples, the variety that produces the best fibers from its leaves. Other steps include stripping, drying, knotting, spinning, and dyeing the fibers. It is also mental, in thinking of a design and making it visible through weaving.

Proud of their skills, the weavers of Miag-ao, Aklan, and Antique learn the craft from a mother or a grandmother, with patience and perseverance as their only capital.

Marañon and Quintos show a Bohol Santo Niño.

Belief and rituals

Floy Quintos, the playwright and director, and Emil Marañon, a lawyer, discuss the woodcarving tradition of the Santo Niño in Cebu and Bohol and the Immaculada Concepcion in Panay.

They compare the conventional Santo Niño statues with folk statues and its many variations, and those made by outliers outside of the Catholic tradition called imagenes repulsivas with the carver’s own interpretation of how the child Jesus should look like.

From the ancient craft of carving anitos to carving santos, anonymous Visayan artisans had imbued their santos with a little animism and a little of the precolonial past.

Sansibar swords, Carigara, Leyte.

Keep them alive and well

Exploring cultural practices in the Visayas, the exhibit takes the viewer inside the process of cooking budbud-kabog, a delicacy of steamed millet cake, weaving piña cloth or mats, embroidering abaca blouses of the Panay Bukidnon, making bamboo fish traps (bubu), chanting epics of Sugidanun in Calinog, Iloilo, and forging bladed iron weapons (itak, bolo, kampilan, sundang and the Sansibar sword of Carigara, Leyte) by a master panday or blacksmith.

The only maker of lagang (shell craft using the chambered nautilus) in Cebu, Richoy Colina, bemoans the day when he is gone and tries to pass on his knowledge to nieces and nephews.

While traditional crafts continue and persist in daily life, they need the support and patronage of mainstream society, in order to flourish on solid grounds for the next generation of Filipinos.

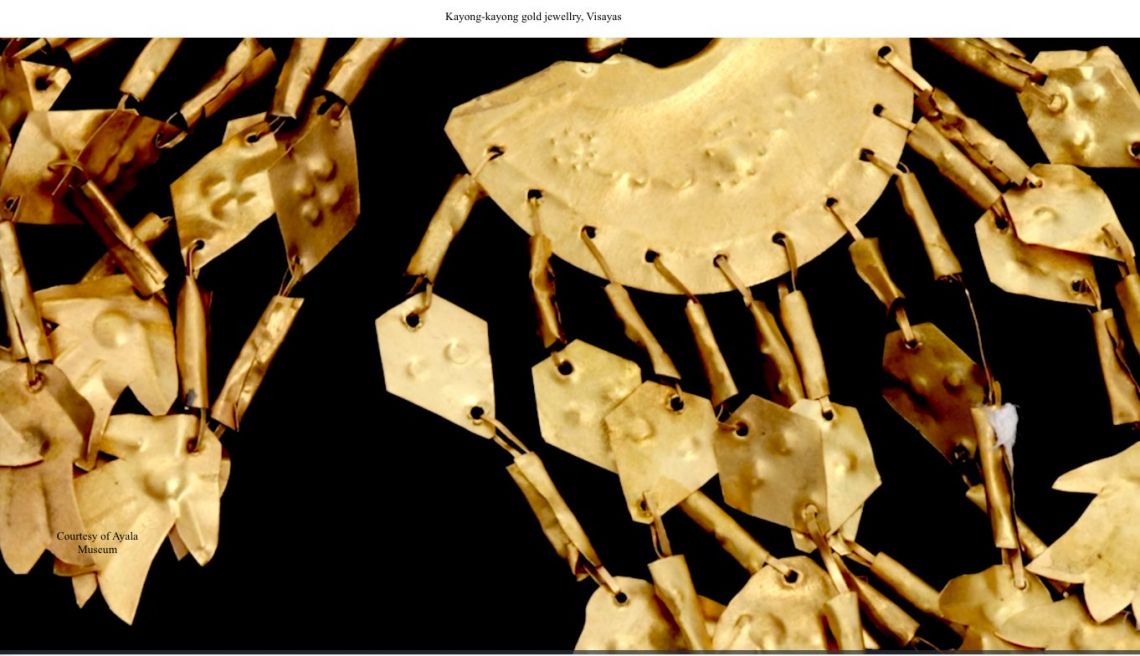

Kayong-kayong gold jewelry from the Ayala Museum gold collection.

The experts

A formidable group of resource persons and scholars in the exhibit explore the history and significance of Visayan heritage to this day.

Felice Sta. Maria presents Pigafetta’s Picnic: Food, Texts, and the Visayas, as recorded by Antonio Pigafetta, the first written record of food and eating in the archipelago.

Some of her books on Philippine food are The Governor-General’s Kitchen: Philippine Culinary Vignettes and Period Recipes, 1521-1935, 2006, The Foods of Jose Rizal, 2015, and the most recent, Pigafetta’s Philippine Picnic (Culinary Encounters during the First Circumnavigation, 1519-1522), 2021.

Florina H. Capistrano-Baker describes pre-Hispanic gold ornaments in the Visayas, and the mastery of sophisticated metalworking techniques long before Spanish contact. The Boxer Codex (ca. 1590) describes Visayan men and women wearing gold chains around their necks and gold hoops around their ankles. Dangling earrings called kayong-kayong with leaves, flowers, tubes, and circles of flattened gold sheets are only found in the Visayas. To illustrate her points, she uses the gold collection of the Ayala Museum.

Capistrano-Baker is the author of Philippine Ancestral Gold, 2011 and Philippine Gold: Treasures of Forgotten Kingdoms, 2015.

Elmer Nocheseda discusses the beauty, utility, and materiality of banig, especially the mats and weavers of Basey, Samar and Leyte in a video titled Philippine Banig Encounters.

An independent scholar, Nocheseda’s book on palm art is the first of its kind, Palaspas An Appreciation of Palm Leaf Art in the Philippines, 2009. He also wrote RaRa: Art and Tradition on Mat Weaving in the Philippines, 2016.