YANGON/BANGKOK – “Anyone in need of oxygen, go soon,” urged a post by a Facebook page called ‘Help You Breathe’, whose followers near 90,000 as Myanmar’s COVID-19 pandemic spins out of control. “Urgent need for regulator, where can I buy or rent,” one user asked. “Where can I refill oxygen in Yangon now?” said another.

Media photos and online posts show crowds waiting outside medical oxygen plants to get the supply they need for sick relatives. Others line up at medical supply shops and clinics in the commercial capital Yangon and other places.

Hospitals and quarantine areas are having to turn away patients, including those who need to be on oxygen support or ventilators. Ambulances queue up outside the Yangon general hospital, yet another sign of the crumbling health system nearly six months after the military took power in a Feb 1 coup.

“We can hardly find oxygen. And when someone needs oxygen urgently at night, we can’t go outside because of the curfew,” said a resident of Thingangyun township in Yangon. “Under the coup, we have been facing so many problems.”

Four people, including two from the same household, have died in his ward, he said.“We heard that there are many people who are ill right now.”

“We can hide from the armed forces, soldiers or police, but we can’t hide from COVID, a knock on the door from the lord of death. My aunt and uncle died on the same day. Others in the family are afflicted too,” said a 43-year-old woman, whose daily routine includes looking for medical oxygen. “I’m always afraid who will be the next one.”

Many are grieving over relatives they have lost to the pandemic — two in a day, three in one week.

For those taking care of ill relatives and friends, meantime, these are days of following daily hashtags like #oxygen15july to keep track of of sources of oxygen. Volunteers have been scouring their neighbourhoods for oxygen – whether in Yangon or Mandalay, Pyay city in Bago region or Lashio in northern Shan state – and sharing this information online. They report the number of oxygen cylinders available where and when, as well as contact numbers.

Medical oxygen prices have soared nearly fourfold to 300,000 kyat (182 US dollars) for a 40-litre cylinder. Oxygen concentrators’ prices have doubled to 2.3 million kyat (1,400 dollars).

But junta leader Senior Gen. Min Aung Hlaing said on Jul 12 : “Most of the people criticise (us) regarding oxygen in recent days. Actually we have oxygen.”

People have been hoarding and profiteering, he added. “They buy the oxygen cylinder and spread the rumour that the country does not have oxygen any more.”

Marjan Besuijen, head of mission for Medecins Sans Frontieres (MSF) Myanmar

A crisis on top of others

This third COVID-19 wave comes on top of a confluence of crises after the coup: the economic crisis, breakdown in basic services, limited humanitarian access, continuing armed conflict, attacks on government offices, and explosions.

A UN brief on the pandemic’s impact showed that Myanmar had, along with Cambodia, the lowest proportion of hospital beds at 9 per 10,000 people from 2010 to 2018.

“With facilities overrun, oxygen supplies limited and vaccine rollout stalled, the situation could become critical in the coming weeks. In some places such as Sittwe in Rakhine State, there is nowhere to get tested,” Marjan Besuijen, head of mission for Medecins Sans Frontieres (MSF) Myanmar, said in an interview.

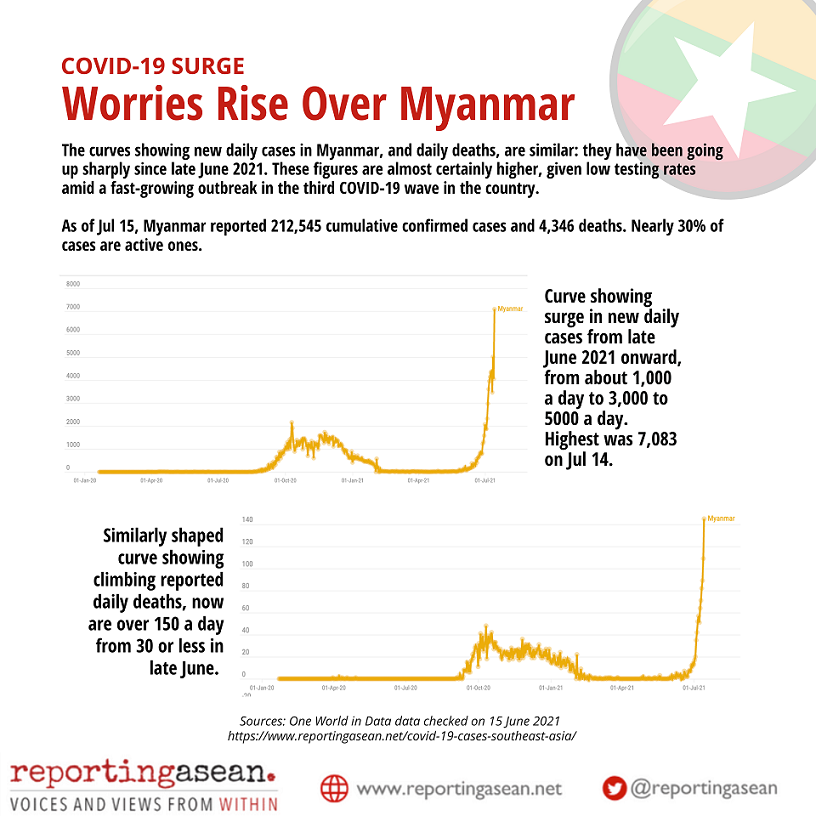

A huge cloud of doubt hangs over Myanmar’s COVID-19 data. Numbers of daily cases, most likely under-reported due to low testing rates, have been spiking from mid-June. New daily cases hit a record 7,038 on Jul 14.

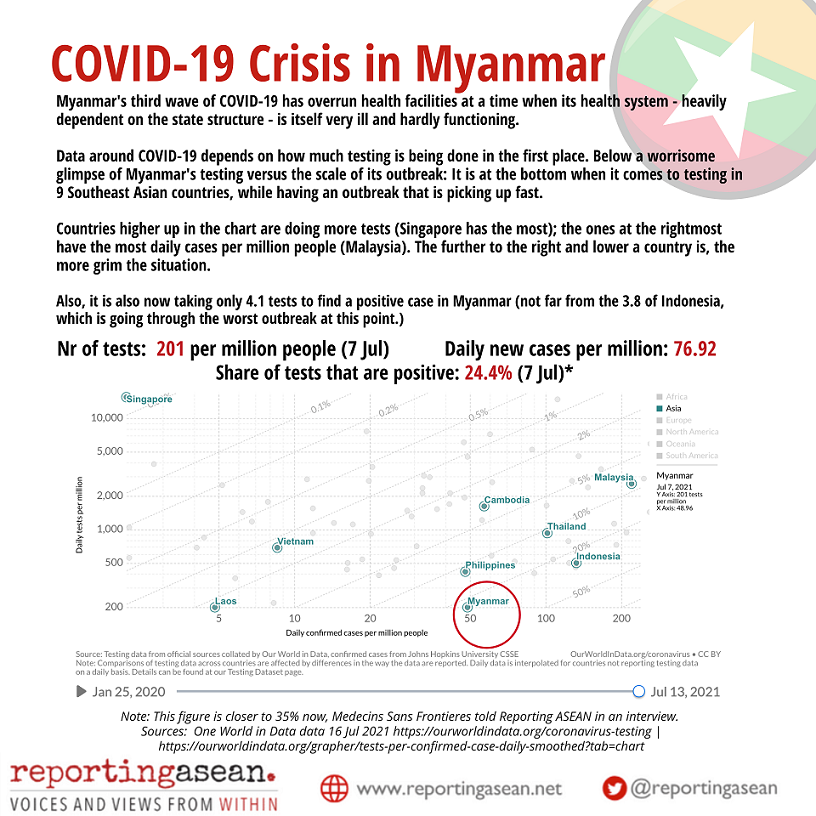

As of Jul 7, Myanmar’s testing rate per 1,000 people was just 0.2, behind the 0.5 of Indonesia, Thailand’s .92 and Cambodia’s 1.61, going by the One World in Data pandemic dashboard.

As of Jul 15, Myanmar reported having a total 212,545 cases and 4,346 deaths. Daily reported deaths have hit 165 at most, which does not look too high but is far from real numbers, as local media point out, since patients are dying at home. Video clips are showing people queueing in wait for their relatives’ bodies – in coffins or wrapped in sheets on stretchers – to be cremated.

“The key figures are the percentage positivity rate, which at 35% is very high, and the fact that record daily numbers for cases and deaths are being broken nearly every day,” Besuijen said. “There is a clear pick-up, but it will be worse than the data reveals.”

The picture around vaccination, which the overthrown government started in January, is hazy too. WHO data on number of vaccinations in Myanmar reflects 3.37 million vaccine doses given as of 4 June (2.81% of population) and no update since then.

COVAX, the global vaccine-sharing mechanism, held back a shipment of 5.5 million doses in March due to the lack of information from the military, WHO Representative for Myanmar office Stephan Paul Jost has said.

The implications of a stuck vaccination program are even more grave at a time when the highly infectious Delta variant is testing the capacities of nearby countries with stronger health systems.

The junta-controlled newspaper ‘Global New Light of Myanmar’ said that 6 million vaccines from China would arrive in the last week of July and early August. Senior Gen Min Aung Hlaing saidRussia would send two million doses of its Sputnik vaccine.

Myanmar had received 3.5 million of India’s Covishield vaccine before the coup, previous news reports said.

On their own

The fraying of state governance, as well as the military’s hunt for doctors in the protest movement and its firing of medical staff, leads many to feel that they are left to fend for themselves.

The ranks of volunteers helping bring the sick to hospitals or quarantine centres, or bring food to those in isolation, are now thinner, says a 34-year-old volunteer from Pathein, Ayeyarwaddy region. “After the coup, military forces were trying to target volunteers. So there is only one-third of volunteers now,” he said.

“We have daily expenses for gas to drive ambulances. They (donations) are not enough for the daily cases,” he said. “So the cases of infection are high, day by day. We have to control them, but how? It’s the urgent thing that the authorities must do right now.”

The health ministry says 60% of Myanmar’s doctors are on duty, but anti-junta doctors dispute this. Doctors on protest have been seeing patientsinunderground clinics, or giving consultations over mobile phone or chat applications.

Civilians queuing for oxygen at a privately-owned oxygen plant on July 11. Photo by Myanmar Now.

But as inspiring as efforts are, these are not enough for the scale of the crisis.

“A nationwide COVID-19 response is beyond the scope of the humanitarian sector – Myanmar desperately needs a comprehensive and coordinated pandemic response, including surveillance, treatment and vaccines, with involvement from multiple levels of society,” said Marjan Besuijen, head of mission for Medecins Sans Frontieres (MSF) Myanmar.

“Eighty percent of Myanmar’s healthcare services are provided through the public system, and this is now operating at a fraction of its capacity,” she said in an interview. Already, the state’s HIV/AIDS and tuberculosis programmes have “barely been operational” since the coup, she added.

The lack of trust in anything the military, or its State Administrative Council, says or does, is not only toxic but life-threatening in a public health emergency.

The “lack of centralised control” undermines the pandemic response, says a Yangon-based general physician with thecivil disobedience movement. “Another problem is the lack of trust in the military. This makes people not obey any of their announcements and instructions.”

Some health workers have refused vaccination, or a second dose, to protest military rule. It is common to hear people say they reject inoculation given out under the junta.

Since late June, the Myanmar military has had to reverse its reopening of public venues. It reopened schools on Jun 1, closed them again from Jul 9. Stay-at-home orders covered 74 out of 330 townships from May 28 to Jul 12, the health ministry said.

At times, having some money and access to oxygen, makes little difference, as a Yangon-based volunteerfound out after her sister was sent to hospital with COVID-19. “There was no bed for her. She had to sleep on the floor in the dark room,” she recalled.“After we gave some money to hospital authorities, she was given oxygen. But unfortunately, she passed away after two days.”

(*This feature is part of the Reporting ASEAN series.)