This year’s Oscar award-winning actor Joaquin Phoenix reflected the politics of food in his acceptance speech when he said, “We go into the natural world, and we plunder it for its resources. We feel entitled to artificially inseminate a cow and steal her baby, even though her cries of anguish are unmistakable. Then we take her milk that’s intended for her calf and we put it in our coffee and our cereal.”

There couldn’t have been more timely words than these at a time when there are loud calls not only from peasant organizations to junk the rice liberalization law but also from social media to rally behind our food growers (hashtag #RiceforRice).

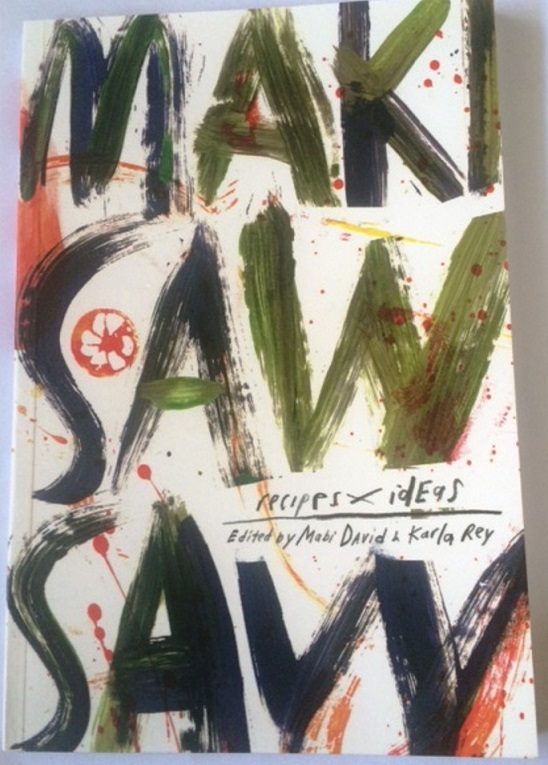

Book cover

The slim book (76 pages) Makisawsaw: Recipes and Idea, edited by Mabi David and Karla Rey and published by the feminist organization Gantala Press, Inc., served initially as a solidarity gesture with the strikers of the labor-contracting NutriAsia. These laborers were violently dispersed last year. The dispersal was symbolized by the bloodied face of grandmother Letizia Retiza.

The contributors to the book waived their fees and royalties so that part of the book sales could be given to the workers’ union Nagkakaisang Manggagawa ng NutriAsia.

Makisawsaw has its offshoot from the Filipino concept of sawsawan which David defined as “the constellation of condiments commonly used to flavor up a dish or customize it to one’s preference.” The word also has a negative connotation as when someone intrudes upon a conversation or others’ business: “Sumawsaw ka naman!” But in the book’s context, makisawsaw becomes a battle cry to claim food and livelihood as the people’s concerns.

Richgail Enriquez, in her essay “Vegan for Every Filipino,” dismissed misconceptions that going vegan is more of a rich person’s option. “…(T)he belief that caring for all beings is the rich person’s problem is not only defeatist, it is also untrue…Filipinos from all walks of life can be capable of being compassionate stewards of the Earth…I used to believe that saving the planet seems grandiose or even overdramatic. It was meant for activists, farmers, scientists, yogis, hippies, politicians and rich people, but not for a common Filipino like me. But Earth does not only belong to them; it belongs to all of us. I live in it, so I bear the responsibility of taking care of it, too.”

At first, she was an animal eater until a nutrition class in the United States opened her eyes to what she should consume. Soon, she was “veganizing” traditional Filipino dishes “to honor my Filipino roots.” She has extended her advocacy through her blog Astig Vegan. She invites people to add aspects of the vegan lifestyle byexploring public markets and buying seasonal produce.

Jenette Vizcocho explained how eating in season has a logic of its own and is kinder to farmers and to one’s health: “…what is harvested in the summer is cooling and watery, but how something harvested in the rainy season is heavier and heartier. Eating this way meant consuming food that supports all the changes within and without our bodies, preparing us for the changes in the season, and if we dive deeper, supporting the phases of our menstruation.”

In her article “Can We Change the World with Food?,” Charlene Tan of the Good Food Community, described as a social enterprise that connects small-holder farmers with urban consumers through community shared agriculture, bolstered the argument in favor of seasonal farming and eating through the words of farmers in Capas, Tarlac: “We used to feel the hunger every lean season (July, August), but this year, because of what we do, we were not hungry.”

Good Food Community has committed itself to buying a minimum amount every week from the farmers. Tan wrote, “When you promise to buy what the farmer grows every week for a whole season, that promise creates the possibility of a chemical-free, just and hunger-free life for the farmer’s family and fresh, diverse, nutritious produce for your family too.”

In “We Have Met,” author Padmapani L. Perez, founding board member of Global Seed Savers Philippines, an organization that advances seed sovereignty among smallholder farmers, assumes the point of view of the seemingly lowly seeds that people throw away after consuming the fruit or vegetable until the time came when these “became the patented property of companies.”

But with orgs like Global Seed Savers rising, farmers and gardeners from both urban and rural areas “are saving heirloom seeds. They’re not putting their precious genetic resources in see banks. They’re putting them in the soil. They’re passing their seeds on to neighbors, friends, children. They’re keeping the power of seeds in the hands of local communities.”

Makisawsaw contains helpful recipes for sawsawan so that consumers need not always buy condiments in supermarkets and groceries. Editor Rey wrote that “at the heart of Makisawsaw recipes is empowering individualsto be more self-sufficient in creating 100% plant-based food that are flavorful and healthy.”

Among easy-does-it recipes are binurong kalamansi, sari-sari store teriyaki sauce, banana ketchup, MSG-free umami paste, easy sayote kimchi. The last section of the book includes recipes and directions for making siopao, cold Asian noodles with peanut sauce, hot and sticky leeks and tofu bowl, Korean-inspired spicy stew, emergency date night pasta, all accompanied with delightful food illustrations in color by Mayang Frigillana.