Only someone with the credentials of Ruben Carranza can tell the story. Once a commissioner in charge of investigation and litigation at the Presidential Commission for Good Government, he was involved in the prosecution of cases against the family of the conjugal dictators Ferdinand and Imelda Marcos that led to the recovery of $680M in ill-gotten funds from various Swiss banks.

His numerous social media posts today are straight arrows in narrating the multiple ways of Marcosian grand thievery from his legal mind’s repository of rich documentation. Trolls who have no information to counteract his first-hand knowledge of the vast Marcos corruption continually attack him, leaving him undeterred of course.

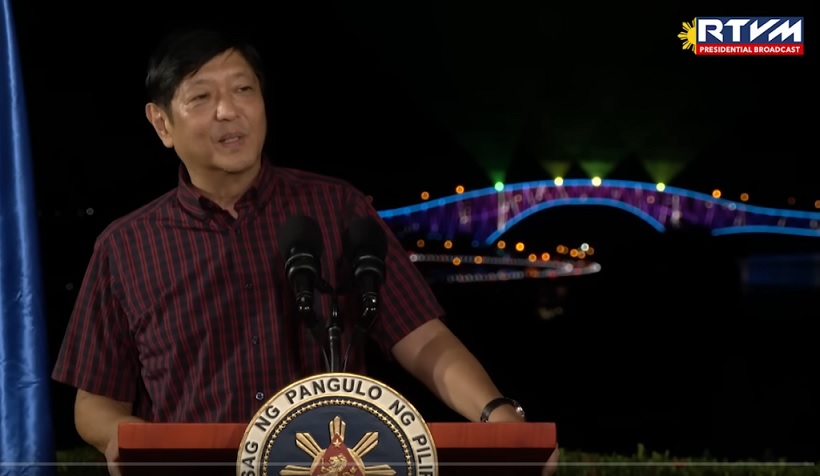

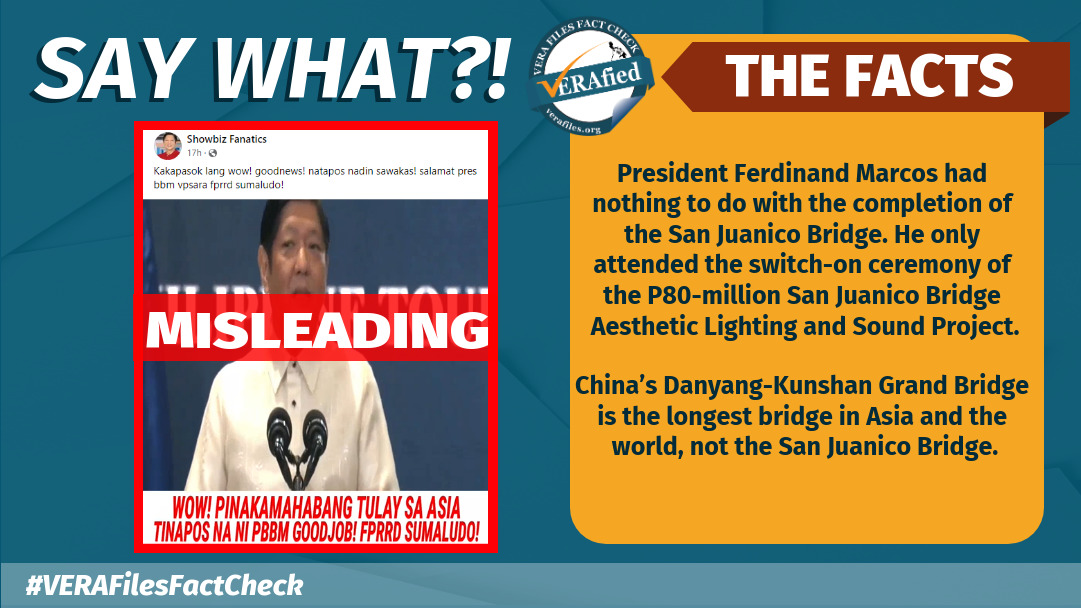

Let the past predicate the present, that is, Ferdinand Marcos Jr.’s lavish ostentation called the Spark San Juanico Aesthetics Light and Sound Project.

Filipino taxpayers paid for the construction of the San Juanico Bridge at a cost of US$22M obtained from a Japanese loan. A plaque at the approach of the bridge says it was named the Marcos Bridge. The Marubeni Corporation of Japan supplied the materials and equipment. The construction was supervised by then commissioner of the Bureau of Public Highways Baltazar Aquino.

“What the plaque doesn’t say is that Marcos received a 15% bribe from Marubeni and other Japanese companies with public works contracts with the dictatorship,” begins Carranza.

“How do we know that?” Carranza supplies the information. After the Marcoses fled in February 1986, Baltazar Aquino came forward to the PCGG with a sworn statement and incriminating documents. The latter included his handwritten notes to the dictator. Aquino asked the PCGG for immunity.

Aquino’s notes were a tell-all. Marcos had tasked him to be the secret collector of those bribes in Hongkong. He was instructed by Marcos to deposit the millions of dollars he had collected in the Hongkong branches of the Swiss banks where the Marcos couple had accounts. Remember William Saunders and Jane Ryan?

On the basis of Baltazar Aquino’s confessions, a civil case was filed in the Sandiganbayan (Civil Case 002). The Office of the Solicitor General and the PCGG requested the court for a “perpetuation of testimony.” The purpose was to ensure that Aquino’s testimony would be perpetuated in future court cases.

The testimony was used in Civil Case 141 that had asked the court for a forfeiture of the Marcos ill-gotten funds in Swiss bank accounts. The PCGG won that case in 2003. Government retrieved a significant part of the bribes received by the Marcoses. The forfeiture judgment was a requirement of the Swiss government as basis to return the stolen monies.

Aquino executed an affidavit that said among the Japanese companies that paid commissions to the dictator were Sakai, Sumitomo, Toyo Trading, Nisshio-Iwai, Mitsui, Marubeni, and C. Itoh. Aquino provided the names of the Japanese representatives of these companies from whom he received the commissions in behalf of the dictator. Readers can peruse his affidavit in the link to Carranza’s Facebook page.

Aquino narrated in his affidavit: “Whenever I would receive commissions on behalf of Mr. Marcos, I would bring the receipts to Mr. Marcos at Malacañang Palace. Mr. Marcos instructed me to keep the receipt of these commissions absolutely secret, and stated that I could not even tell my wife.”

The Japanese Diet would later discover the Marcos payola. Because of it, the National Legislature enacted new anti corruption laws to make sure no such corruption by foreign heads of states like Marcos were sourced from Japanese War Reparations funds. The Marcos Japanese Official Development Assistance (ODA) scandal became known in Japan as Marukosu giwaku. The Marcos name in Japan became synonymous with graft. The lessons from the Marcos scandals were among the reasons why Japan created its 1992 ODA Charter.

The San Juanico Bridge inauguration took place on the birthday of the conjugal half -Imelda Marcos- on July 2, 1973. Among her guests whom she loved to invite to give the world a false veneer of a “jetset” lifestyle were the socialite Cristina Ford and the concert pianist Van Cliburn. Tasked to manage the huge catering for a cover of 5,000 for breakfast, lunch and dinner was Arthur Lopez, then the banquet manager of the Manila Hilton Hotel.

Lopez’s main contact was Benjamin “Kokoy” Romualdez, Imelda’s brother who was Leyte governor. Lopez gave him a list of the gigantic needs for the catering: ocular inspection of the reception site in Tolosa, Leyte; ferry all the ingredients and kitchen equipment from Manila; fly 200 service staff from Manila; fly the main kitchen brigade on-site to set up the kitchen, cooking and service facilities including marquees, ice carvings, flowing fountains a week before the event; unlimited blank Philippine Airlines tickets to and from Leyte to ferry men and machine. “Done!” responded Kokoy Romualdez.

Lopez narrated: “Kokoy not only amazed me with his lightning-speed responses, he also upped the backup component of this massive operation by assigning the Army, Navy and Air Force to be at my disposal. The feeling was so exhilarating that wow! It looked like a scene from Francis Ford Coppola’s Apocalypse Now. The food and service were first-class and everything went like clockwork.”

The total tab amounted to over P1M. Lopez related: “It was the first time in the history of any catering contract. In today’s inflationary rate, what would that cost?” When he tried to collect, Kokoy was suddenly unreachable. Immigration Commissioner Edmundo Reyes helped Lopez by contacting the Chinese Chamber of Commerce. “It took a while to raise the amount,” Lopez said. In short, the Marcoses did not pay Manila Hilton.

And so we go back to Bongbong Marcos’s light and sound display at the San Juanico Bridge. The cost of his project was P80M. Poverty incidence in Samar today is 37%; Leyte’s is at 39.1%, among the poorest provinces in the country. In 2021, the agriculture budget for Samar was P66.034M.

All extravaganzas. No substance. That is how he leads. Spectacular.

The views in this column are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of VERA Files.