It will be full-blown nostalgia time when Lino Brocka’s Bona closes the 20th Cinemalaya at the Ayala Malls Manila Bay on Saturday, August 10, 8:30 p.m. with lead stars Nora Aunor and Phillip Salvador in attendance.

Like the director of Jose Rizal (Marilou Diaz-Abaya) who died in 2012, the director of Bona (Brocka) won’t be around as he died in a car accident in 1991.

The screenings of Jose Rizal and Bona are Cinemalaya’s tribute to the country’s cinema icons.

The 4k restoration of Bona was supervised by Carlotta Films. It was earlier screened this year at the Cannes Classic Showcase in France and at the Cinemalibero section of the Il Cinema Ritrovato Festival in Bologna, Italy. It will also be seen in the retrospective section of the Toronto International Film Festival.

Italian reviewer Pier Giovanni Adamo wrote upon seeing the restored Bona: “The greatness of Brocka’s cinema lies in having understood the lifeless without a way out of an oppressed country. In the harsh colors and nocturnal references of Bona, the slums of Manila become the perfect scenes to stage a very original melodrama, in which the even raw immediacy of mass cinema, parodied by the scenes on the sets of Gardo, is twisted by Brocka’s visceral style. Perhaps it’s time to add a name to the list of authors of the ‘cruelty cinema’ theorized by Bazin: Von Stroheim, Dreyer, Sturges, Buñuel, Hitchcock, Kurosawa, Brocka…”

Bona was cited as one of the 100 Best Films in the World, by the Museum of Tolerance in Los Angeles, California. It was also screened at the 47th Vienna film fest where film historian Barbara Wurn described the lead actor as “the awesome Nora Aunor.”

Some years back on Brocka’s 23rd death anniversary, Cinema One gave him a special tribute with a pilot episode of a talk show “Inside Cinema Circle” aptly called Mga Anak Ni Brocka hosted by Boy Abunda.

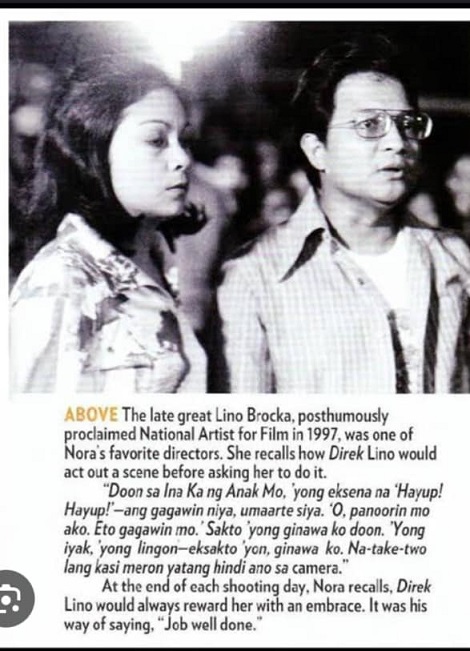

Gathered for this occasion were Brocka’s proteges namely Phillip Salvador, Bembol Roco, Rio Locsin and Chanda Romero, among others. What the talk show revealed was that Brocka got the best performances from these actors some of whom happen to be personally close to the director.

Roco recalled he was a virtual beginner when he was tapped for the lead role of Maynila Sa Mga Kuko Ng Liwanag after a chubby Ilagan was eased out from the part. But with the magic of Brocka, Roco said he was able to summon the best that he could give to the part even with his then non-existent theater and film credentials.

The talk show became veritable teleserye as Roco became very emotional and cried recalling what a wonderful person Brocka was and a first-rate director. This was echoed by Locsin and Romero who revealed they didn’t know they could act until Brocka came along and gave them self-confidence.

But the most revealing recollection was from Salvador who appeared in other landmark Brocka films like Jaguar, Orapronobis, and Bona, among others.

Salvador said Brocka was not just a director to him. He was also a big brother and probably a special friend. “I loved him and I love his family,” Philip declared. To be sure, they had their share of misunderstanding but in the end, they were able to patch up differences.

Philip recalled: “The last time we saw each other after we reconciled, Lino (Brocka) kissed me on my lips in full view of construction workers in the neighborhood. He loved me, he said and I told him, I love you, too. It didn’t occur to me that he would soon die and leave us forever.”

The art and life of Brocka is summed up in the Cultural Center of the Philippines (CCP) publication, Lino Brocka: The Artist and His Times edited by the late Mario Hernando.

The book has assorted articles on Brocka’s life including film reviews of his landmark films.

In the book was this author’s 1977 review of Brocka’s Inay in the Bicol Chronicle. “How did Lino get that review? “I asked the editor. “The paper is only read in Albay.”

Hernando told this author he got my review from a scrapbook of clippings Brocka personally kept.

The CCP book confirms Brocka was a true-blooded Bicolano (he was born April 3, 1939 in Pilar, Sorsogon) and had a traumatic childhood made worst by close relatives.

From Sorsogon, he grew up in San Jose, Nueva Ecija, studied at UP where he had short theater stints in the company of Wilfredo Ma. Guerrero and Behn Cervantes.

The best account in the Hernando book was Jo-Anne Maglipon, “Brocka’s Battles.”

Here, she summed up Brocka’s battles with the board of censors from Maria Kalaw Katigbak to Manoling Morato including his private battles that included a discovery of a family secret.

Maglipon wrote: “To the day he died, he wasn’t done. These last years, the world began to appear to him bigger, more urgent. His political cinema had found its groove. There seemed to be an outpouring of stories to tell in his celluloid: Of the wives and mothers and daughters who waited for their men in prison, of corruption in government, of morals ran aground, of little men’s little joys. He spoke about birds and scuba diving, and how he could never get used to fast cars. He tried up cleaning his finances and investing his money somewhere wise. In his last days, he was still slugging it out merrily for those he held dear, and still hurting friends miserably that had cared for him. ‘Twas said that the man’s judgment was not always the best; his heart not always wise. He was, after all, of many wild and immodest passions driven. He had will, he was stubborn, he was flawed. But always, he was significant. There was no way a man like Lino Brocka would have left the world the same way he found it.”

One’s link with Brocka started in 1970 when he was still working with producer Miling Blas of Lea Productions with offices at Escolta.

One religiously followed his films from Tubog Sa Ginto until Maynila Sa Mga Kuko ng Maynila, Jaguar and some of his theater productions from Fort Santiago to Philamlife Theater.

In 1979, he agreed to be godfather of my daughter Kerima who was named after our favorite writer, Kerima Polotan.

He recalled that he read all Polotan’s articles in the Philippines Free Press and that he was a big fan.

“One time,” he recalled,” I went to Fort Santiago where she (Polotan) was delivering a lecture. I attended that lecture and I couldn’t help staring at her intently. I wanted to hug her and say, ‘I love all your articles!’”

The last time one witnessed Brocka’s temper was at the Manila Metropolitan Theater in the concert of Spanish diva Montserrat Caballe with pianist Lorenzo Palomo in 1979.

Before the concert, Brocka (a future National Artist for Film at the time) threatened to douse Rolando Tinio (a future National Artist for Theater) with ice cream during the intermission.

This was an offshoot of a film festival controversy when Tinio and everybody else on the filmfest jury raved about Celso Ad. Castillo’s Burlesk Queen and dissed Brocka’s entry, Inay.

One begged Brocka not to make a scene, because Caballe was a world-famous personality in opera.

An ice cream-dousing scene in the middle of song recital would surely make headlines not just in Manila but in The New York Times, Paris Match and Le Figaro.

The last time I saw him was when my daughter and I saw him crossing the Pasig street after a kidnap scene in Bayan Ko Kapit Sa Patalim starring Gina Alajar, among others. My daughter and I were aboard a jeepney and I called him out and say, “Lino, this is your goddaughter Kerima.”

He smiled looking at his goddaughter — who like him — would turn out to be another activist.

Brocka’s Bona stars Nora Aunor and Phillip Salvador with screenplay by Cenen Ramones and photographed by Conrado Balthazar. It was produced by Nora Aunor’s film outfit, NV Productions.