By ELIZABETH LOLARGA

THE Diliman Book Club, which meets every Saturday at the ROC Restaurant at UP Balay ng Alumni at the Quezon City campus, usually discusses social sciences and politics with the author of the moment.

THE Diliman Book Club, which meets every Saturday at the ROC Restaurant at UP Balay ng Alumni at the Quezon City campus, usually discusses social sciences and politics with the author of the moment.

These meetings start mid-afternoon, but stretch way past the restaurant’s closing time because the members are an argumentative lot.

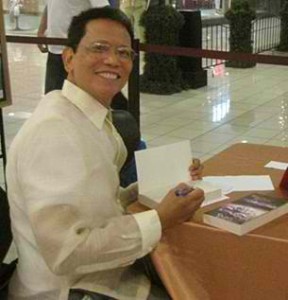

The discussion over Mario Miclat’s controversial historical novel Secrets of the 18 Mansions (Anvil Publishing Inc.) was no exception.

Henson Laurel, a retired philosophy teacher and club organizer, gave the book’s précis for those who hadn’t cracked open a copy yet: It is the author’s experience with the communists from the time the Communist Party of the Philippines (CPP) was re-established to the time he and wife Alma left for China.

He described Miclat as one of the writers of the party paper Ang Bayan. He was also a part of its translation bureau and educational department.

The novel chronicles the stay of the CPP group that was sent on exile to China.

Laurel explained: “Jose Ma. Sison wanted to ensure that the CPP leadership would continue by having a Party group on permanent exile in China. That way, if officers and others in the Philippines were either arrested or killed, the survivors in China would take over.”

Miclat denied criticism that the writing of his novel was a way of pagbubuhat ng sariling bangko (a Filipino expression that literally means “carrying one’s one bench” or “tooting one’s own horn”).

He said he wrote the novel “from my heart based on the real stories of real people, not people in the abstract, not caricatures of courageous peasants and oppressive landlords. It is the story of individuals who define a generation. It shows the dissonance between revolutionary theory and revolutionary practice.”

He continued: “If personal safety was my consideration, I wouldn’t have written the book or have it published. I wrote it for love of the masses, for the nation and the truth.”

Miclat consciously came from a long tradition of Asian authors who depicted a parallelism between real-life events and the authors’ lives like Jung Chang’s Wild Swans, Qian Zhongshu’s Fortress Besieged, Han Suyin’s A Many-splendored Thing and Cao Xueqin’s Dream of the Red Chamber.

He has in his gloaming years proceeded to enjoy his life since he has realized that it is short. He said. “This is life—it can be intimidation or a true concern.”

Miclat, who teaches at the UP Asian Center where he also serves as dean, saw it was the ripe time to write his novel after he joined then UP Chancellor Sergio Cao on an official trip to China a few years ago.

The younger Cao had asked him who Jaime Florcruz, Eric Baculinao and Chito Sto. Romana were. The three, former Filipino activists who also lived in exile in China until they decided to live and work there, had invited their group to dinner.

He described their life in China as “very privileged,” saying: “I thought we would be living in communes. Later, the authorities allowed me to live with my wife in the countryside but as guests of the Chinese Communist Party’s central committee. We lived in a compound made up of underground communist movements in other countries. As guests, we were free compared to the typical Chinese. Our toilet was huge—you can put a ping pong table in it and play comfortably.”

The novel has generated controversy and alienated Miclat from former comrades because he has been accused of giving a false portrayal of the CPP and Sison, who is disguised with the initials “A.G.”

Miclat said: “I just wanted to tell a story. I wasn’t disputing anybody. I don’t have personal enemies. I don’t tend to accuse people or talk badly about people. I described a situation, why it has reached a point because of so many factors.”

The novel took him six years to write because there were many historical asides and with history, he had to be “very factual by looking at the archives and the libraries. I reviewed a lot of incidents, going back to the picture of a boy who died at the Plaza Miranda bombing.”

Still, the novel is a “product of the author’s imagination, a story despite the research for facts,” he said.

The book club members agreed that a novel must stand on its own, but since the author was present, they could ask him what his intention was and if he succeeded.

Miclat said he tried to adhere to Plato’s statement on the classical “greater truth” by telling the truth in telling the story.