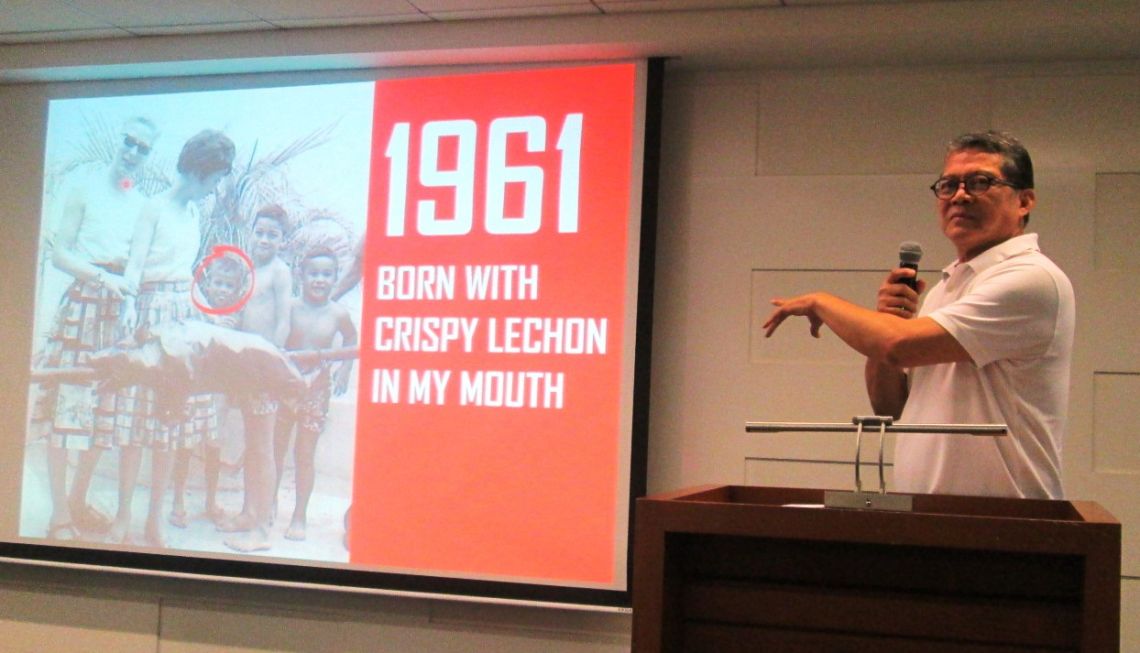

Claude Tayag has pork running in his veins as he shows a picture from his childhood.

At what appears to be the First Chicaron Convention in the World at the Bayanihan Annex of Unilab in Mandaluyong City, Claude Tayag, chef, restaurateur, visual artist and writer, opened his presentation by saying , “No other nation in Southeast Asia has this obsession, or rather, fatal attraction with the pig, especially its crispy, crackling chicharon.”

In his talk entitled “Everything you want to know about chicharon,” sponsored by the Museo ng Kaalamang Katutubo whose building will have its groundbreaking in June 2020, Tayag traced the origin of the crispy delicacy to the Spanish colonizers.

He quoted Antonio Sánchez de Mora, chief of the Archivos General de Indias in Sevilla, Spain, as writing in an email interview about how chicharron (note: Spanish spelling) originated in the Andalusia region, southern Spain, where most colonial seafarers came from.

De Mora added that in Cadiz, one of the provinces where the ships embarked to the New World, the seafarers “brought with them their food ways, including all things pork, especially its curing into jamón, tocino (bacon), chorizos, and chicharrón. All former Spanish colonies have their version of chicharon, differing in shape, size and seasoning. In the central and northern parts of Spain, though, it is called torreznos or cortezas.”

It may just be that chicharon, as Pinoys know it, may have been around since pre-Hispanic times. Tayag fell back on what the late food critic and historian Doreen G. Gamboa wrote in her book Tikim in the chapter on “The Flavors of Mexico in Philippine Food and Culture: Indigenization, when a foreign name is adopted”: “The grains, fruits, vegetables, and dishes that traveled from Mexico to the Philippines are not only recorded in history, but are especially engraved in the language. The Mexican/Spanish names have persisted, and have been adapted into the vernaculars, without being replaced by local names. Where there is no local name, but only a Mexican one–Filipinized or not–therefore, the Mexican origin is quite clear.”

Bagnet from Ilocos

. Chicharon from Carcar, Cebu

Tayag, author of Food Tour, co-author with wife Mary Ann Quioc of Linamnam:Eating One’s Way Around the Philippines and of Kulinarya wherein he also served as food stylist, shared the many ways chicharon is called in Philippine provinces and regions: bagnet in Ilocos Norte; okilas (skin only) in Ilocos Sur dipped in dinardaraan (all-blood dinuguan); pititian in Pampanga (bite-size chicharon; from the root word titi or to fry in its own fat); and agas or tacas in Bicol which is still chicharrones, que quedan de la manteca or what remains of the rendered fat.

In short, he said, “The fried thing is native to us.”

Because he hails from Pampanga he described himself as having “pork in my veins.” He quipped, “Siguro magkakaroon ng rebolusyon dito kung mawalan ng chicharon sa mga kalye (Maybe a revolution will break out if chicharon disappears from the streets).”

Daboy backfat from Sta. Maria, Bulacan

Chicharong bituka

He cited the many ways chicharon is eaten not just by itself as a snack. Its other applications include toppings for pinakbet, pancit palabok, batchoy, crispy dinuguan or monggong guisado.

Even a comfort food such as paksiw na bangus can be topped with Pampango titian. He described the resulting texture in the mouth as “something crunchy, something soft” with the added flavors of saltiness from soy sauce and sourness from vinegar.

He listed what he called “the great pretenders of the chichaworld,” meaning, starch-based cracklings whose ingredients are flour, starch, transfat, artificial flavoring, artificial coloring, preservatives and msg.” These “pretenders” include: kropek, pop rice, fish crackers, fried macaroni, miki chicharon and caramelized kropek.

The Pinoy’s favorite dip for the chicharon is vinegar. Tayag said, “Of all the basic tastes, it is perhaps sourness that defines Philippine cuisine. With vinegar as one of the most indispensable ingredients in the Filipino kitchen, it has been used for centuries not just for seasoning, dipping sauce, but as a natural preservative as well. In the pre-refrigeration era, it was common knowledge that cooking with vinegar will prolong the dish’s shelf life without refrigeration, most especially with our hot tropical climate.”

He added that vinegar reflected the Filipinos’ fondness for just “a touch of sourness in dishes like kinilaw, paksiw, sinigang and even adobo.” Chicharon pairs well with the suka (vinegar as it is called in Tagalog, Ilocano and Cebuano), silam (in Ibanag and Ivatan), aslam (Pampango) and langgaw (Ilonggo).

During the open forum, Tayag was asked to rank the top chicharon in the country. Instead, he answered by describing what he didn’t like in some chicharon: “Pagkagat mo matigas yung lutong. Dumidikit yung pulp sa gilagid at ngipin (When you bite into it, the crunchiness is hard. The pulp sticks to your gums and teeth).”

Tayag gestures as he calls ice cold beer as best pangtulak for chicharon

As for the best pangtulak (beverage) to go with chicharon, he said without batting an eyelash, “Ice cold beer or Coke Zero.” Now that’s really artery-clogging!