By YASMIN D. ARQUIZA

THE legal battle over the ban on aerial spraying of poisonous pesticides in Davao City, which has reached the Supreme Court, is not the first case in which farmers square off against big agribusinesses over the issue of public health.

But it is the first time that farmers have the city government on their side. The city government in fact went as far as imposing a ban on aerial spraying of pesticides, through an ordinance banana companies say is unconstitutional and which is now the subject of the legal tussle.

“This is a landmark case on health and environment, which highlights the obligation of local government units to protect the public welfare,” said Lia Esquillo, executive director of the Interface Development Interventions (IDIS). The environmental group is assisting local communities in their protest against aerial spraying.

The joint committees on environment, agriculture and health of the city council, in their report, aptly described the controversy as a case of “public health and environment vs. local economy.”

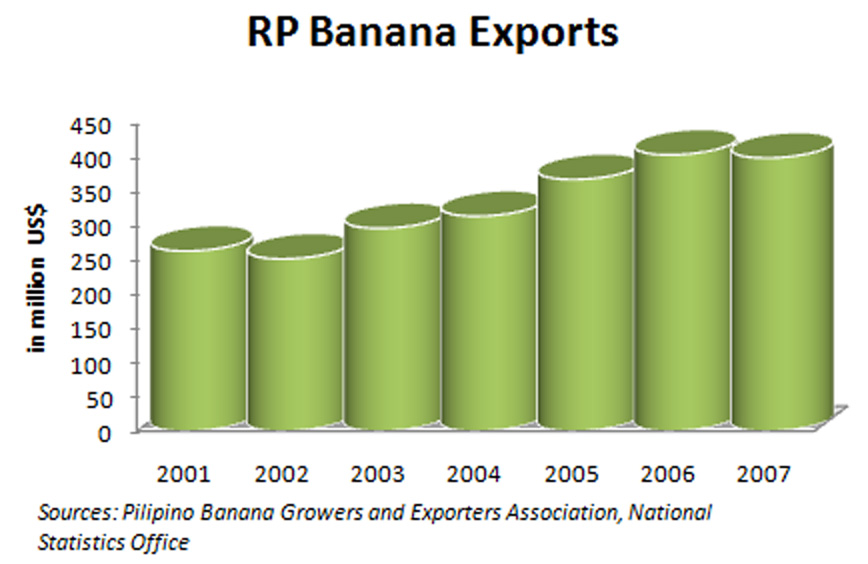

Bananas provide more than 75 percent of export revenues in the region, making it Davao’s No. 1 dollar earner. The Philippines is the fourth largest exporter of bananas in the world and, together with leading exporter Ecuador, has posted the highest growth rates in the industry in recent years, according to the Food and Agriculture Organization.

Bananas provide more than 75 percent of export revenues in the region, making it Davao’s No. 1 dollar earner. The Philippines is the fourth largest exporter of bananas in the world and, together with leading exporter Ecuador, has posted the highest growth rates in the industry in recent years, according to the Food and Agriculture Organization.

The case is not the first one involving controversial pesticide use in banana plantations in Davao. In 1993, banana workers in Davao del Norte were among 16,000 banana plantation workers who filed a class suit in Texas, USA against chemical companies that manufactured the pesticide DBCP, or dibromochloropropane.

A $41.5-million settlement was paid in 1997 by the companies, although refusing to admit fault or liability. They claimed DBCP pesticide, which was found to cause sterility in men, was not used properly.

Aggrieved parties

In the current case, both the farmers and banana companies feel they are the aggrieved party. The companies were the ones who initiated court action to stop enforcement of an ordinance banning aerial spraying of pesticide. They filed a case against the city government with the Regional Trial Court for “violating the equal protection clause of the Constitution” after the local legislation took effect in March last year.

The Pilipino Banana Growers and Exporters Association (PBGEA), Davao Fruits Corp. (DFC) and Lapanday Agricultural and Development Corp. (LADC) said the city ordinance constitutes “unreasonable exercise of police power” because banning aerial spraying would be “tantamount to confiscation of property without due process of law.”

An immediate shift to ground spraying would cost banana companies P882 million in potential losses, the petitioners said. They also questioned the requirement of a 30-meter buffer zone to protect neighboring farms and residents from pesticide drift, saying this would greatly reduce the area of banana plantations.

In September last year, the lower court upheld the validity of the city ordinance. It said the experts presented by the banana growers merely gave “unsupported allegations” and “theoretical analysis” on the health and environmental risks of aerial spraying.

Judge Renato Fuentes gave weight to farmers’ testimonies of “simple lives, gravely affected by a concerted problem, confronting them in their everyday existence.”

The banana companies elevated the petition to the Court of Appeals, which granted in November a temporary restraining order allowing the banana companies to resume aerial spraying.

In January, the court issued a preliminary injunction, citing the “apparent unconstitutionality of the ordinance, albeit inconclusive.” It further stated that the ordinance “seriously invades the appellants’ right that will cause them irreparable injury if not protected.”

Under the new Rules of Court, the CA should have decided the case by July this year, or six months after it granted the preliminary injunction, according to lawyer Raymond Salas of the legal advocacy group Saligan, which is assisting the farmers.

When the CA failed to do so, the city government and the farmers elevated the case to the Supreme Court last July 25, questioning the injunction order, which had effectively prevented the enforcement of the ordinance.

“Mere allegations of unconstitutionality cannot be enough for the Court of Appeals to issue a preliminary injunction,” Salas said.

The farmers, in their appeal, argued that “the conduct of aerial spraying, being a mere method to release toxic substances over an area, is not a right under the law. By concluding otherwise, the Honorable Court of Appeals commits clear and grave abuse of discretion.”

Even the Office of the Solicitor General upheld the action of the city government. In response to the appellate court’s request, Assistant Solicitors General Magtanggol Castro and Charina Soria issued a legal opinion last June 20 that the banana companies had failed to show the ordinance was unconstitutional, and that the city had simply followed the general welfare clause of the Local Government Code.

On the other hand, banana companies found support from the Department of Trade and Industry in Region 11.

DTI Regional Director Merly Cruz said in a position paper submitted to the city council that Davao’s leading banana industry directly employs 12,000 workers in the plantations. Support services such as stevedoring, trucking, packaging and security indirectly link up 100,000 more workers to the industry.

Public nuisance

After collating all the data, the joint committees on environment, agriculture and health of the city council issued their report, which said in part: “We have heard both sides of the issue: Public health and environment vs. local economy. The two are of great importance to any civilization. But when both factors collide, the policy of the State comes in to shed light and to remind us of the basic framework in which the government is created.”

“Pesticides are poisonous, aerially spraying it is a nuisance, banning its aerial application is a justified response,” the joint committee asserted. “Can anyone imagine an urban area being aerially sprayed with pesticides? What makes the life and safety of the inhabitants of a community in nearby agricultural entities less? To remain indifferent to the plight of those being aerially sprayed with pesticides is inhuman.”

Davao City has the biggest population in the region: 1.3 million people compared to less than one million each for the three Davao provinces and Compostela Valley, according to the latest National Statistics Office figures. Its population density and status as a major urban center have made it a flashpoint in the aerial spraying controversy.

However, the city is not the first to enact legislation against aerial spraying. In 2001, the provincial board of Bukidnon passed its own ordinance against the practice, saying “unstable wind direction” while applying pesticide could pose danger to people, animals and crops. The ordinance noted that “poultries, piggeries, cattle ranches and other agri-based businesses and residential areas abut farm boundaries” of banana plantations.

The city ordinance has sent ripples in the neighboring province of Davao del Sur. During the Earth Day celebration last April, Gov. Douglas Cagas publicly criticized aerial spraying, citing the results of a health study in a village beside a banana plantation.

“Traces of pesticides that are being aerially sprayed were detected in their blood samples and water resources. If this practice continues, I am not providing my constituents a healthy body and environment that they inherently deserve,” he said.

Provincial board member Merlin Bello, who chairs the committee on health and agriculture, said he has attended many community meetings where residents have complained about aerial spraying in banana plantations. He has expressed support for the passage of a similar ordinance in Davao del Sur.

Alan Sanggayan, president of a local association called Lambigit, said their group has submitted a petition to the provincial government calling for a ban on aerial spraying due to health concerns and environmental pollution.

Sanggayan is a member of the Kalagan indigenous community in sitio Budoy in Barangay Guihing, Hagonoy town, where vast areas are devoted to bananas. Successive expansion of the plantations since the 1970s has hemmed in the 700 families living inside the ancestral land claim on all sides, which have to contend with pesticide spray.

Near the market of Hagonoy, a bulletin board indicating the supposed date of spraying is blank, despite regular aerial spraying in the area. Elders of the Kalagan people said they are rarely notified about the schedules. They are also complaining about the more potent nematicide applied on the ground, and the stench of boom spray in other areas.

Organic bananas

Even before the city ordinance was proposed, environmentalists have reported cases of pesticide poisoning from various application methods, expansion into watershed areas, and conversion of rice and fruit farms into banana plantations.

“The aerial spraying issue epitomizes the ills of corporate agriculture,” Esquillo of IDIS said. “Corporate-led plantations and mono-cropping are the real problems.”

She said farmers’ cooperatives in Mindanao are already producing organic bananas, and many have gone into diversified plantations or intercropping to control diseases.

In the farming district of Calinan, farmer Cecilia Moran said most of her neighbors have leased their coconut farms to banana and pineapple growers that practice mono-cropping. Only farmers in the village of Malagos grow bananas under their coconut trees.

Davao businessman Jesus V. Ayala, a longtime industry player, has ventured into the production of upland Cavendish bananas using organic methods through his Tristar group. The company has toured city officials in its plantations, presenting the farm as an environment-friendly model of corporate farms near watershed areas.

The move is in line with the city government’s Jacinto report, which recommended that “long-term use of organic pesticides should be adopted” in banana plantations to eliminate health and environmental risks to surrounding communities.