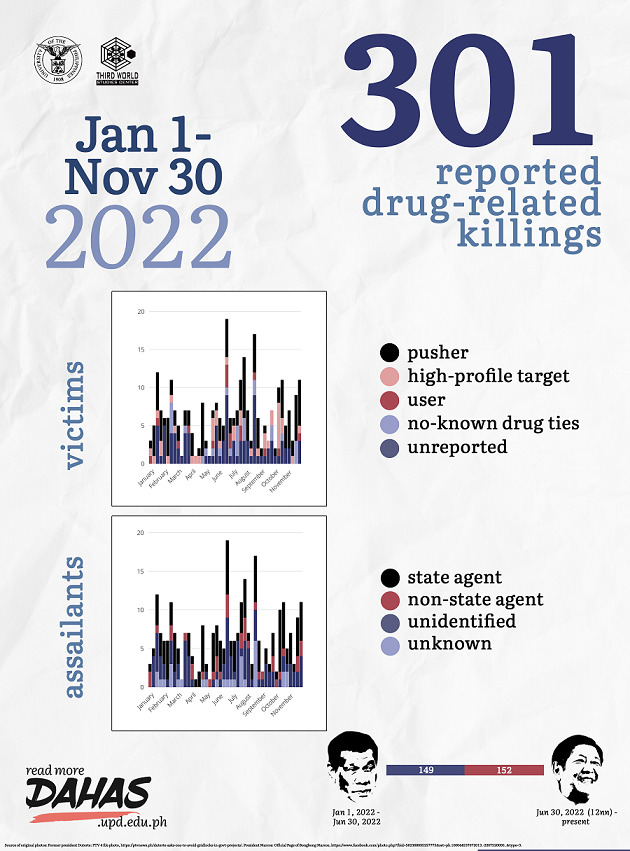

Even as President Ferdinand Marcos Jr. adopted a different strategy from the Duterte administration’s brutal war against illegal drugs, the killings continue on the high side, data gathered through the Dahas Project of the University of the Philippines Third World Studies Center showed.

In the first five months (July 1 to Nov. 30) of the Marcos administration, the Dahas Project data showed 152 drug-related killings, already exceeding the 149 killings recorded during the final six months of the Duterte government (Jan. 1 to June 30).

During the first half of the year under Duterte, the average daily rate was 0.8. So far under Marcos, the rate stands at one per day.

What is considered a drug-related killing?

The Dahas Project does not limit its definition of drug war killings to those committed by state agents resulting from police operations. The war sprawls over a whole criminal complex beyond state authorities, and includes various criminal elements with varying intent to harm their victims. Failing to account for these casualties, as the government’s own effort continuously does so, offers a limited view of how the drug war accumulates its fatalities.

In light of the need for a much broader scope, the database considers a killing related to illegal drugs if the victim was killed through violent means (e.g. beaten to death, shot, stabbed) and meets at least one of the following criteria: (1) killed in a drug-related operation, activity, or encounter, (2) reported to be involved in the drug trade or in the war on drugs in whatever capacity (e.g. alleged drug personality, law enforcer, informant, etc.), (3) reported to be in possession of illegal drugs at the time of the killing or when the body was found, (4) reported to be associated with someone involved in the drug trade, and (5) killed by someone reported to be involved in the drug trade for drug-related reasons or while under the influence of drugs.

Law enforcers still lead in drug killings

Of the 152 killed under the Marcos administration, 71 or 46.7% were committed by state operatives, usually the PNP or PDEA; much higher than the 65 killed in the first half of 2022.

For both periods, 44 were killed during official anti-drug operations in which the “nanlaban” narrative — of a drug suspect violently resisting arrest thereby necessitating their killing — retains its currency across police reports. Despite these figures being drawn just from online news sources, it lands worryingly close to PNP’s own numbers reported by its current chief of police, Gen. Rodolfo Azurin Jr. In a forum organized by the Foreign Correspondents Association of the Philippines last Nov. 12, Azurin disclosed that 46 drug suspects were killed in various anti-drugs operations carried out by the PNP and PDEA.

The PNP has denied allegations of undercounting raised by the Human Rights Watch (HRW).

Col. Jean Fajardo, spokesperson for the PNP, said “police operations are tallied into the data system of the PNP” and that “it will be very difficult to change that because that is in the system of the PNP.”

However, such claims to diligence are put into question with Azurin’s statement in a Sept. 19 press briefing when he claimed zero drug war casualties from Sept. 1-17. However, days before the briefing, specifically on Sept. 12 and 13, two casualties resulting from anti-drug operations were reported by multiple news sources that cited PNP and PDEA officers. The casualties were William Dionisio and Hideki Hernando.

So far under the Marcos administration, drug-related killings carried out by non-state elements still hold a sizable share in the total count of casualties. Forty-seven or 30.92% were killed by unidentified assailants, 18 or 11.8% by non-state agents (members of armed groups or identified private individuals), and 16 or 10.53% by unknown assailants (incidents where there were no witness accounts of incident). Included in these categories of killings were cases of body dumps — corpses of alleged drug suspects left or thrown in secluded areas. In the first five months of the Marcos government, 15 such cases had been reported, two more than what were recorded during Duterte’s final six months.

Pushers remain as top targets

Out of the 152 killed from July 1 to Nov. 30, at least 65 or 42.76% were low-level drug peddlers. High-value targets, on the other hand, hold 23 or 15.13% of the total killings, a much higher share compared to Duterte’s last six months when they accounted for 12% of the fatalities. Compared to Duterte’s last six months, the ratio between high-value targets and pushers killed under Marcos is negligibly lower; still standing at around three pushers killed for every high-value target. Six or 3.95% of the casualties were tagged as drug users, while 15 or 9.87% reportedly had no links to the drug trade such as “collateral damages” and officers killed in action. The level of involvement of 43 victims were not identified in the news reports.

New hotbeds of drug-related killings

During Duterte’s last six months in office, Metro Manila was consistently the top hotspot for drug-related killings. Data shows that under Marcos, Cebu and Davao del Sur registered the highest number of killings, with 22 killings each. Metro Manila placed third with 16.

Since the second week of October, at least one killing a week has been recorded in Cebu, mostly carried out by non-state elements. In Davao del Sur, on the other hand, a spike was observed in drug-related killings, all of which curiously happened in Davao City and mostly resulting from the police’s anti-drug operations. This starkly contrasts to the single drug-related casualty reported in Davao del Sur during the last six months of Duterte’s presidency.

A “new” drug war

On Nov. 26, the Department of Interior and Local Governance (DILG) and the PNP formally launched the latest iteration of the drug war, the “Buhay Ingatan, Droga’y Ayawan (BIDA)” program, directing efforts to be focused on demand reduction and rehabilitation. Though not done away with completely, police operations were said to take a back seat and to emphasize respect for human rights. Since 2016, however, the drug war has countlessly been renewed or rebranded, but the killings have shown no let-up. Regardless of whether this most recent version does pave a new path and drastically mitigate lives the drug war continues to claim, much blood has already been shed.

(This piece is part of the University of the Philippines Third World Studies Center’s on-going research project, Dahas. The project’s output can be accessed at dahas.upd.edu.ph. For the latest in the running count of the reported drug-related killings in the Philippines, follow @DahasPH on Twitter.)