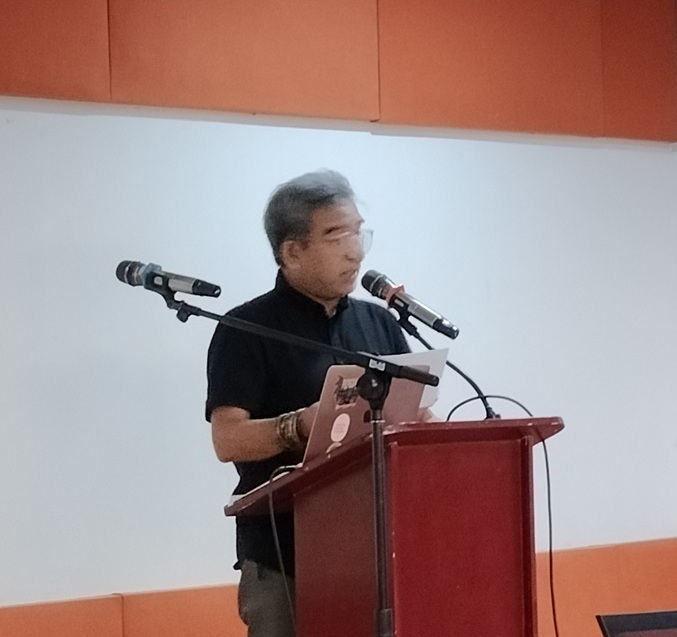

Thumbnail photo of Leonard Co from Leonard Co’s Digital Flora of the Philippines website.

Maria Makiling’s anger at the continuing degradation of the environment and the death of Leonard Co 15 years ago would both be acutely felt if Philippine literature and science intersected.

The former is Mount Makiling’s guardian spirit and, as the legend goes, is benevolent to the community until her ire is roused. The latter, an esteemed Filipino expert in ethnobotany and a staunch environmental defender, was killed on Nov. 15, 2010, along with co-scientists Sofronio Cortez and Julius Borromeo, while doing fieldwork in Kananga, Leyte.

Co’s death anniversary last month was marked by the national alliance Environmental Defenders Congress (EDC). And to honor his legacy of commitment to grassroots science, the Constantino Foundation (CF), University of the Philippines Diliman’s College of Science (CS) and Institute of Biology, and Green Convergence launched the inaugural Leonard Co Lecture Series at the CS Auditorium on campus on Nov. 21.

The lecture series is the brainchild of the mathematician and former UP Diliman chancellor Fidel Nemenzo, according to CF managing director Red Constantino.

Ruel V. Pagunsan, chair of UP Diliman’s Department of History, delivered the introductory lecture titled “Branches of History: Trees, Empire, and Nation.”

‘Passionate scholar’

Co, who entered UP Diliman in 1972, was “a passionate scholar who knew plants more than anything else,” Nemenzo said of his friend in his opening remarks.

”His purpose in life was to discover real knowledge and share it with others. He reminded UP to stay true to its calling [of] nurturing imagination and creativity,” Nemenzo said.

Writing on Facebook, Jerry B. Grácio said Co was fluent in English, Hokkien, Ilocano and Mandarin and spent many years in the Ilocos and the Cordillera while writing “Medicinal Plants of the Cordillera.”

Grácio also posted Co’s unforgettable counsel that the brain is used not only to store information but also to think about things: “Ang utak, hindi lang ginagamit para mag-imbak ng impormasyon, kundi para pag-isipan ang mga bagay.

Co and his colleagues Cortez and Borromeo were on fieldwork when they were killed by soldiers of the 19th Infantry Battalion then engaged in a counterinsurgency operation called “Oplan X-mas Gift.” The soldiers mistook the scientists as insurgents and shot them dead. In its Facebook post, the EDC said Co had cried out to the soldiers that he and his colleagues were unarmed: “Tama na, hindi kami armado!”

The case remains officially unsolved as the court is yet to hear the defense’s proposed reduction of charges from murder to “reckless imprudence resulting in homicide,” the EDC said. It demanded full accountability from the 19th Infantry Battalion soldiers for the killing of Co and his colleagues.

In the same post, Co’s widow, Glenda Flores-Co, said: “Leonard was a man whose expertise in botany we cannot underestimate. He was not merely a botanist; he was [also] an environmental defender. You cannot teach botany or the love for native plants in the classroom. Kailangan mo dalhin sila sa gubat (You must bring them to the forest).”

The EDC said the ethnobotanist documented 122 medicinal plants in the Cordillera, supported more than 50 community health programs, and expanded his work to the endangered ecosystems of the Sierra Madre, Palawan, and Eastern Mindanao. (Ethnobotany is the study of the dynamic relationship between people and plants, bridging botany and anthropology to understand traditional ecological knowledge and biocultural diversity.)

‘Green colonialism’

Pagunsan’s inaugural lecture was an eye-opener on forests and the American colonial government.

He began by discussing how Co championed archiving local materia medica and advocated for “teaching about local scientists.” Both are ways to counter the “green colonialism” that, Pagunsan said, utilized the environment in the governance of the Philippines.

“The basic premise of green colonialism was aligning the colonial environmental projects with what the US needed,” he explained. “The idea was to control or limit the human presence for the colonial state to maximize its use at the expense of the local cultivators.”

Pagunsan said the advocacy for the restoration of forest cover was biased towards fast-growing exotic hardwood trees — i.e., mahogany — that were marketable in America. The conversion of forest lands into state reserves — later national parks — excluded local cultivators and prevented indigenous practices. He pointed out that making the forests harvestable was a continuation of the American colonial policy because the policy was to “plant useful economic trees for the self-sufficiency of the Bureau of Forestry.”

He said the US reforestation program in the Philippines officially started with the founding of the School of Forestry on Mount Makiling in 1910. This was followed by the first state-initiated large-scale reforestation in Cebu in 1916 and the establishment of the Reforestation Administration in 1960.

Nationhood

Pagunsan said reforestation became a matter of cooperation between the government, private entities like the Manila-based The Findlay Millar Timber Company, and lumber companies, with mahogany as the favored reforesting crop planted across the archipelago.

At this juncture, forest restoration became linked to nationhood in the postwar reforestation policy. “The forest is heritage, so a good citizen is someone who knows and protects the forest. It’s a pillar to nation-building and [destroying] it is to destroy the future,” Pagunsan said.

A slide from his presentation quoting the 1911 Annual Report of the Bureau of Forestry — “Reforestation [was] an important national program” — underscored the program’s significance. He said Mount Makiling became the laboratory of the program, with scientists experimenting on various tree species for mass cultivation and authorities devising ways to stop or control kaingin, the slash-and-burn farming technique for clearing the land for crops.

Pagunsan cited two reforestation projects. One, Loboc-Bilar Reforestation in Bohol, was established in the 1950s and was hailed as the most successful program in the post-Commonwealth era even if it took a decade for the water supply to stabilize. But the area was a “biodiversity dead zone,” he said, because “mahogany was poisonous to the indigenous species; organisms and other animals were absent; and tarsiers couldn’t cling to the tree trunks.”

The manmade forest is now a tourist spot, with visitors passing it en route to the famed Chocolate Hills, he said.

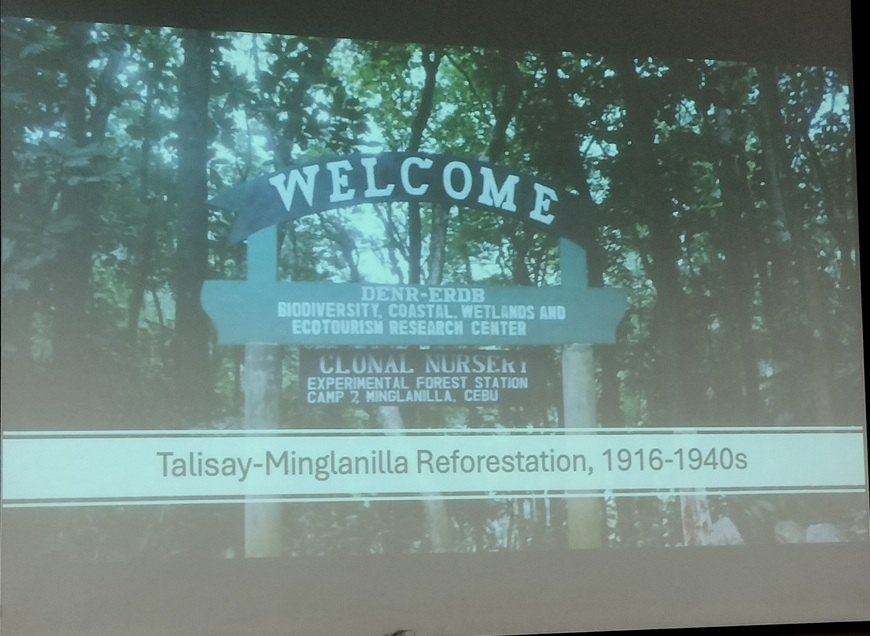

The other project is Talisay-Minglanilla Reforestation in 1916 that scientists called an “ecological waste” despite being “the first reforestation project outside of Manila that received large funding in the Commonwealth era,” Pagunsan said, adding: “It’s still flooded today.”

Contradictions

Pagunsan argued that mahogany was detrimental to the country’s ecological system because the local cultivators — the kaingeros (farmers who practiced kaingin) — were demonized as “criminals who prevented economic development.” The stark incongruity of the program with the reality of national parks sprouting in the Philippines — i.e., Makiling National Park, established in 1933 — moved Pagunsan to ask where the native trees are.

The general scenario was laid out by Pagunsan in answering a question from a member of the audience about any attempts by America to package forests together with US President William McKinley’s “Benevolent Assimilation” policy.

“The extraction of the forests was packaged as bringing progress to the nation, the industrialization of our forests and seas, and a society [in which] people should participate in order to progress,” he said.

Queried on what laws protected the forests amid America’s concurrent nation-building and deforestation activities, he said: “The use of machines by US companies quickened deforestation. It’s paradoxical, with the creation of national parks [and] the deforestation, but the laws allowed for the deforestation. This is what we should look into. Americans weren’t going to write [the laws].”

He added that the Indigenous People’s Rights Act of 1997 can protect Philippine flora because the law seeks to recognize, protect, and promote the rights of Indigenous Peoples in the country. But he expressed skepticism about the National Greening Program (NGP), saying “the trees planted were invasive, not indigenous.”

The NGP was launched by then President Benigno Aquino III in 2011 and was aimed at planting 1.5 billion trees by 2016 to combat poverty, food insecurity, and climate change. It’s unclear if the target was met.

Green consciousness

Pagunsan is not an ethnobotanist, but he sees no divergence between his field of history and Co’s métier. Answering a question on how he can connect the two disciplines, he said a historian must see “the indigenization in the discipline and to decolonize from it.”

He advocated for Filipinos “to look for more [Leonard] Cos who ask where the local scholars are.” He said we should “study our own pioneers in history, mathematics, and science.”