When two commissioners of the three-person Independent Commission for Infrastructure quietly stepped down this month, and no major political figure spent Christmas behind bars despite repeated assurances from the Palace, the image of an aggressive anti-corruption drive began to fray.

The flood control scandal, once framed as a defining test of accountability, now poses an unavoidable question: Has the campaign lost its force just when it mattered most?

Presidential Communications Secretary Dave Gomez insists that more personalities linked to anomalous flood control projects will be “thrown behind bars in the New Year.” But after weeks of unmet expectations, such declarations sound less like reassurance and more like an extension of broken promises.

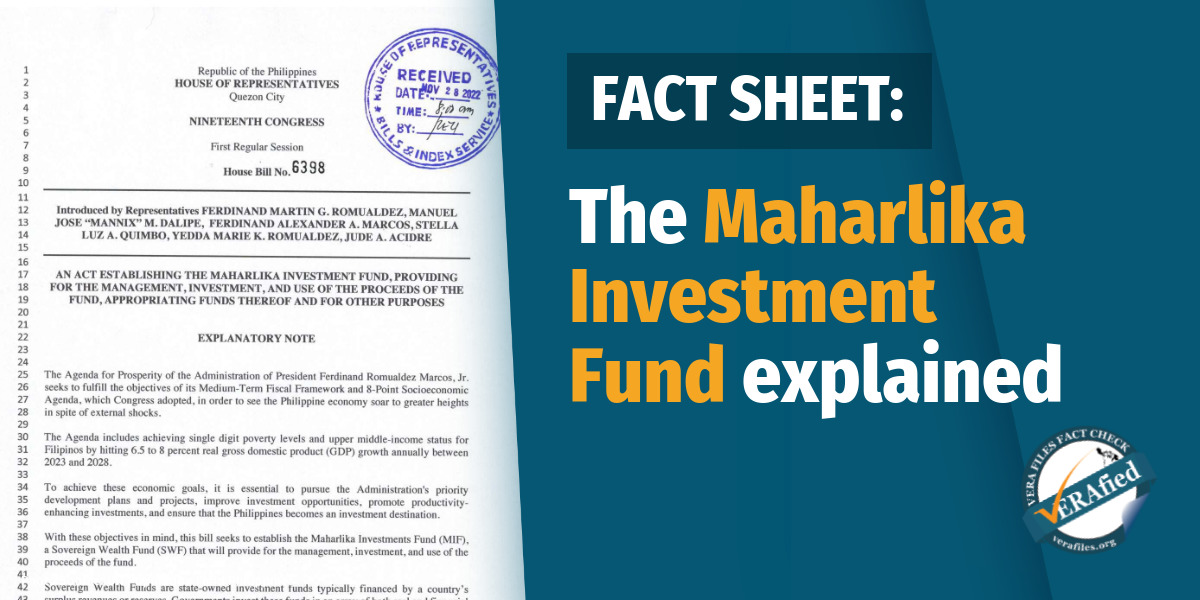

The timing deepens public skepticism. President Ferdinand Marcos Jr. is set to sign anytime soon the proposed P6.793-trillion national budget, one that budget watchdogs say still contains pork barrel-like items that could once again place public funds at the discretion of politicians. If corruption in infrastructure is indeed being confronted, the persistence of these mechanisms raises doubts about the administration’s resolve.

Last Friday, the ICI announced it was wrapping up its probe into alleged irregularities in public works projects following the resignation of commissioner Rossana Fajardo, effective Dec. 31. Her exit followed that of former Public Works secretary Rogelio Singson, who resigned earlier this month. Both said they had already contributed their expertise to the ad hoc body created by Marcos last September amid mounting public outrage over billions of pesos allegedly siphoned off through substandard or non-existent flood control projects.

Critics, however, see these departures as confirmation of a deeper flaw: the commission was never equipped with the authority, manpower or logistics needed to pursue the so-called big fish, from budget preparation to project implementation.

Without subpoena power, witness immunity or prosecutorial teeth, the ICI risked becoming more symbolic than consequential.

Public pressure has also visibly ebbed. Turnout at protests against the multi-billion-peso scandal has dwindled, fueling concerns over activist fatigue. Political analysts warn that thinner crowds reflect growing disillusionment, easing pressure on the administration to pursue powerful figures. While organizers have floated another mass action in February, timed with the 40th anniversary of the 1986 People Power revolt, the momentum that once drove the issue into the national spotlight has undeniably slowed.

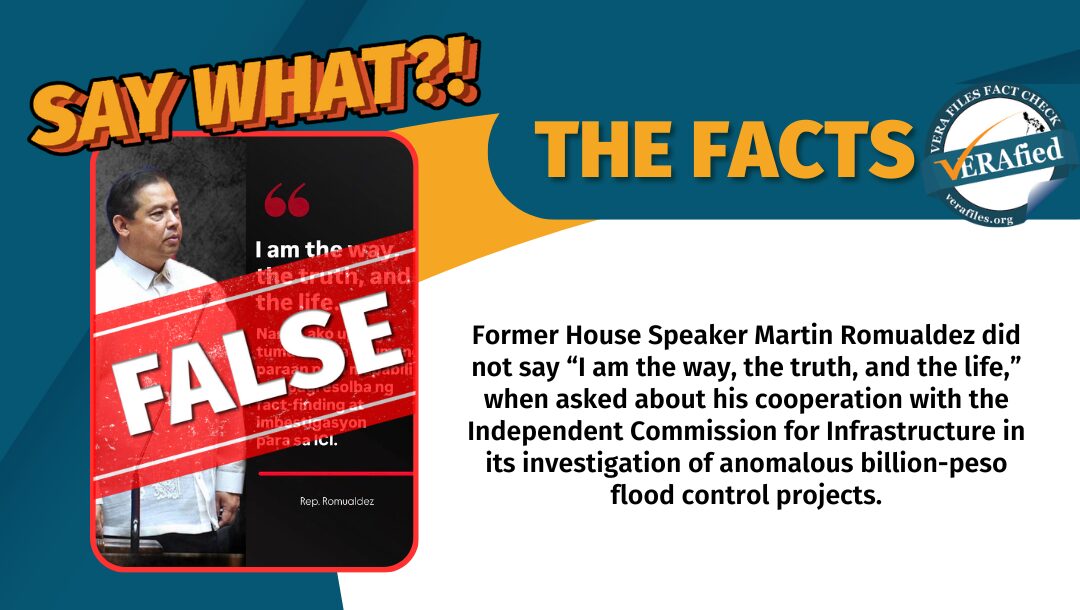

The legislative front offers little reassurance. The Senate investigation has stalled, with several congressmen, among them former House speaker Martin Romualdez, declining to appear despite allegations that they benefited from kickbacks linked to flood control projects. Delays in summoning key officials and witnesses have prompted accusations that the probe is more performance than pursuit, a cover-up rather than a reckoning.

Some lawmakers now fault the executive branch for a sudden loss of enthusiasm in empowering investigative bodies, renewing calls for an independent people’s commission with real authority, including the power to grant witness immunity.

To counter perceptions of a slowdown, Gomez points to the detention of contractor couple Sarah and Curlee Discaya as proof that the accountability drive is merely in its early stages. Sarah Discaya was arrested on Dec. 18 over a P96-million ghost flood control project in Davao Occidental and is detained in Lapu-Lapu City Jail, while Curlee Discaya remains held in contempt by the Senate.

“The flood control investigation does not end on December 25,” Gomez said, stressing that it has been underway for just over four months.

Indeed, the administration can cite concrete actions: the Anti-Money Laundering Council has frozen more than P5.2 billion in assets tied to the scandal, and eight officials from the Department of Public Works and Highways have been arrested.

But numbers and assurances alone do not sustain credibility. What the public now demands is consistency, urgency and unmistakable political will. Without them, the promise of accountability risks dissolving into yet another anticlimax, another corruption scandal that begins with fire and ends in smoke.

The views in this column are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of VERA Files.

This column also appeared in The Manila Times.