Aware of its critical role in Philippine politics, Meta (formerly Facebook) has vowed to prioritize mitigating risks of coordinated campaigns across all its applications seeking to manipulate public debate in the forthcoming elections.

Article One, a specialized strategy and management consulting firm with expertise in human rights, in an independent human rights impact assessment, found a majority of its respondents, mostly online users and journalists, reporting “personally seeing political misinformation on Facebook.”

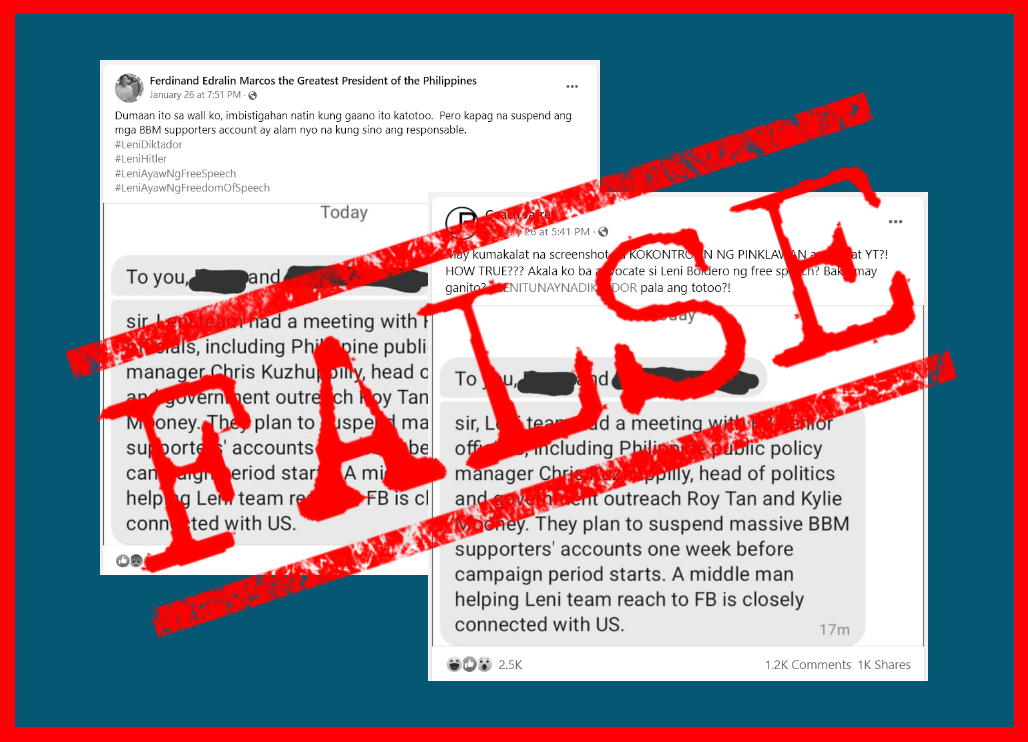

“Political disinformation can impact users’ rights to free expression, access to information, and political participation,” it said. The study aimed to look at the human rights risks in Meta’s platforms—Facebook, Instagram, WhatsApp—and address them through global policies and standards. The consulting agency further noted that disinformation was being used “to influence voter perceptions” and “target political opponents.”

From March to June 2020, Article One surveyed 2,000 Facebook users and interviewed 22 Philippine-based stakeholders, including civil society organizations, journalists, members of the academe, and human rights defenders, with the assessment completed last August.

Stakeholders were concerned about the misinformation spread through Facebook Messenger, the exemption of politicians’ posts from fact-checking, and the ongoing presence of fake accounts on the platform that form disinformation networks and harass activists.

To stop coordinated inauthentic behavior, Meta said in a Dec. 2 response that its security teams have “identified and removed over 150 covert influence operations,” including those in the Philippines, since 2017.

In a 2019 report, Nathaniel Gleicher, head of Meta’s Cybersecurity Policy group, said one activity used a combination of authentic and fake accounts to disseminate content on Facebook, with a total cost of US$59,000 in advertising expenses.

Its investigation found that it was linked to a network organized by Nic Gabunada, a public relations practitioner and social media manager of President Rodrigo Duterte in 2016. (See Nic Gabunada’s amazing social media network)

“They frequently posted about local and political news, including topics like the upcoming elections, candidate updates and views, alleged misconduct of political opponents, and controversial events that were purported to occur during previous administrations,” Gleicher wrote.

On banning political ads that include disinformation, however, Meta said it is only partly implementing the recommendation. Its policies prohibit content and political advertisements that misrepresent who can vote, dates, times, locations of elections, and qualifications or materials required for voting.

“We do not allow third party fact checking on the direct and unedited speech of politicians because we believe that by censoring the speech of politicians, we’d leave people less informed about what their candidates or elected officials say, and leave politicians less accountable for their words,” it said.

Meta outlined other efforts aimed to further reduce online misinformation and disinformation: launching a civic education campaign with the Commission on Elections (Comelec) and various organizations such as the Legal Network for Truthful Elections (LENTE), conducting training on their Community Standards, and holding roundtable discussions with civil society.

Addressing online harassment and other human rights risks

Given the sheer volume of Filipino users on Facebook and Meta’s other social media platforms, the report highlighted six other salient human rights risks: online harassment, incitement of violence, surveillance, sexual exploitation, human organ trafficking, and extremist activity.

“For most of these human rights risks, there is clear guidance from human rights standards and domestic legislation to inform a rights compatible response from Meta,” Article One said.

In the case of mis- and disinformation and online harassment of vulnerable groups, the firm noted that “the balance between free expression and the protection of other rights is less clear.”

While research on red-tagging cases in 2020 and 2021 on Facebook alone did not lead to imminent arrest or murder, Article One stated that:

“The killings of several individuals that had been red-tagged both online and offline indicates that [it] remains an urgent and severe threat to human rights defenders and one that can infringe on the right to life and security of a person.”

After President Duterte signed the Anti-Terrorism Act (ATA) in July last year, there was “an increase in terrorist tagging,” which put critics, political foes, journalists, and human rights advocates “at risk of extrajudicial execution.”

In 2020, VERA Files found that among 332 pieces of online disinformation, including those from Facebook, 22 had to do with ATA and red-tagging.

Of the number, 13 had to do with red-baiting, and almost all of its targets were female personalities. Nearly half were about Kabataan Party-List Rep. Sarah Elago. (See VERA FILES YEARENDER: Red-tagging online ramps up as Anti-Terror Law takes effect in 2020)

One post insinuated a connection between CPP-NPA and Rowena “Weng” Paraan, head of ABS-CBN’s citizen journalism arm Bayan Mo, Ipatrol Mo. The National Union of Journalists in the Philippines and the International Federation of Journalists both condemned this.

In response, Meta said it has “updated its bullying and harassment policy,” including strengthening protections against gender-based harassment for everyone, including public figures.

For journalists and human rights defenders, who have become famous because of their work, it offers “more protections” such as removal of unwanted sexualized commentary and comment controls on Facebook and Instagram “to limit engagement during spikes of increased attention.”

As to the current health crisis, some organizations have pointed out a “downward trajectory” in internet freedom with the shutdown of ABS-CBN, one of the country’s largest news outlets, and ramped up arrests of human rights activists.

Thus, the pandemic will also shape how Meta “addresses existing and intensified human rights concerns related to its operations and products.”