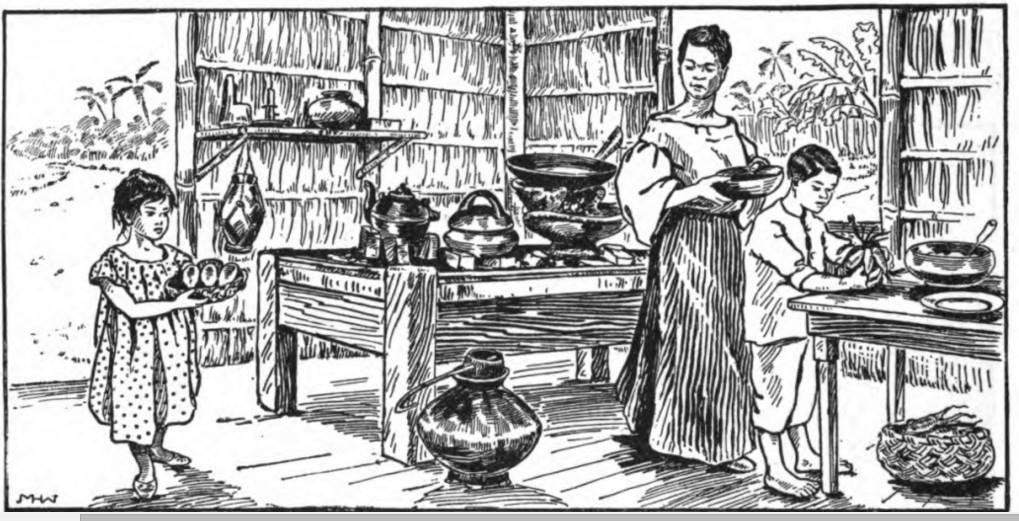

In traditional Asia, the floor of a dwelling is a multipurpose space for social gatherings, eating, and sleeping, a cultural practice that still exists.

Philippine families have used mats on the floor for eating on banana leaves with their bare hands, or on their heels around a low table called dulang (the term also refers to a wooden food platter). Among the affluent in Spanish Philippines, eating on the dining table with chairs was de rigeur.

Uncle Sam (1898-1948)

In 1892, Manila’s first electric company La Electricista, provided electricity in Manila; Manila Electric Railroad and Light Company (MERALCO) was granted a franchise in 1902 to provide electricity to Manila and surrounding areas. Manila Gas Company piped gas into urban homes.

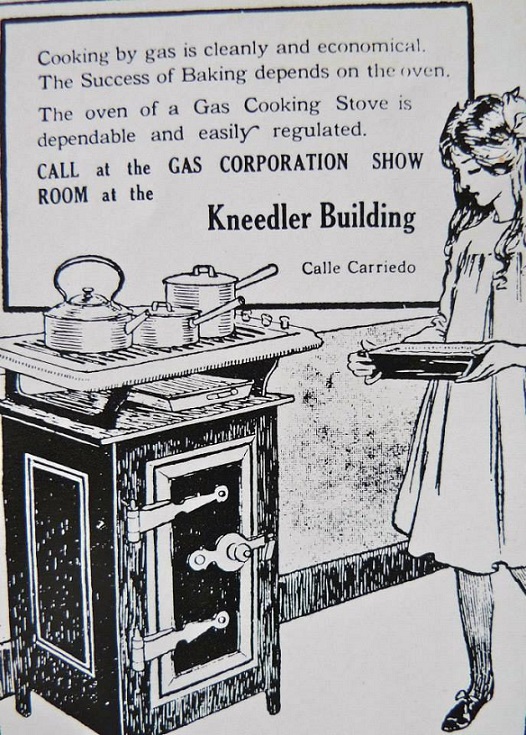

Under American colonial rule for 50 years, the country witnessed significant changes in preparing food, cooking, and eating. Advertising for gas and electric kitchen appliances as modern, convenient, and time-saving fuels generated the highest sales, with Manila’s affluent the first to adopt new cooking methods. Such appliances appealed to the image of a modern Filipino woman and the idea of a clean, germ-free kitchen.

Manila Gas Corporation’s advertising campaign promoted gas as “the ideal cooking fuel,” “faster, cheaper, better, more dependable” for the “modern” woman. Meralco promoted electricity as part of “the modern affluent lifestyle.”

With ice available albeit expensive, advertisements in the 1920s for “refrigedoras” referring to iceboxes started appearing. Extending the life of perishable food, an icebox is a wooden box with shelves; its topmost part lined with metal where a block of ice is stored, cooling the lower shelves.

Home economics

The Bureau of Education introduced domestic science or home economics in 1904 through the public education system established by the Americans in 1901. It stressed sanitation and hygiene in food preparation and healthy living in tropical Philippines. Alice M. Fuller, an HE teacher in Tuguegarao, Cagayan published the first HE manual on housekeeping and household arts for elementary schoolgirls in 1911.

Public school instruction stressed the importance of nutrition and hygiene to Filipinos in their everyday lives. School kitchens introduced new kitchen appliances, sanitary food preparation, menu planning, and the use of tableware and knives and forks. Domestic science also introduced baking of breads, cakes, and pastries to Filipino school girls, using Western ovens.

In contrast to the dirty, smoky, and sooty Filipino kitchen, domestic science classroom kitchens presented a clean one with some equipped with chimneys to direct the smoke out and hoods with ventilators.

Llamas in wrote in Philippine Craftsman (1916): “Before the coming of the Americans, the sanitary system was so poorly organized that thousands of people died every year from preventable diseases. People knew little of importance of cleanliness.”

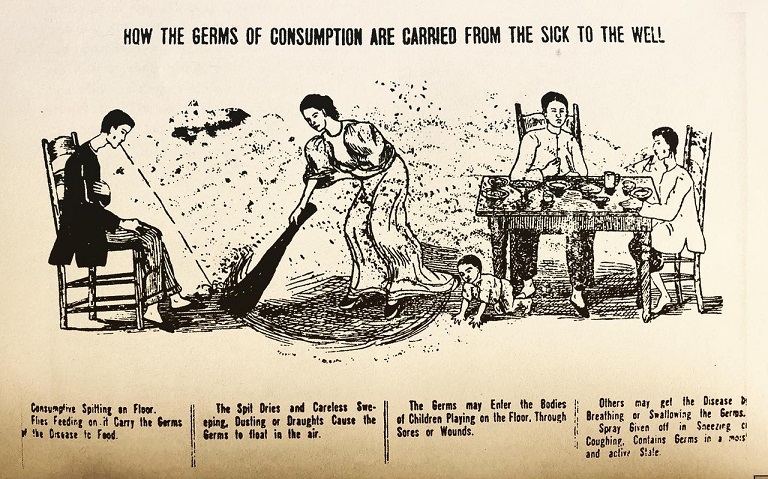

Throughout the 19th century and the early 20th century, the country experienced several waves of the cholera epidemic with a high number of fatalities. In 1903, tuberculosis was the third leading cause of death among Filipinos, after cholera and malaria.

Today, 121 years later, the Philippines ranks third in the world (after South Africa and Lesotho) with the highest prevalence rate of tuberculosis, a highly curable disease. With its TB rate increasing every year, about one million Filipinos have active TB disease. Every day more than 70 Filipinos die of TB needlessly, says the World Health Organization (WHO).

Germs and filthiness

The idea of germs as the cause of sickness became a focal point in the American public health campaign. Eating on the floor or a dulang was discouraged because it was close to the filthy floor. The kitchen with its kalan-stove and dirt had to go, said the Americans.

Modernity was equated with hygiene and sanitation. Gas and electrical appliances were promoted as symbols of modernity and affluence, the American way.

“Just touch a button”

Western companies, mostly American, launched aggressive advertising campaigns on the latest home and kitchen appliances such as water heaters, toasters, percolators, grills, pressure cookers, stoves, and refrigerators. Bottled mineral water “with radium,” Tansan, was available early on

The Manila Gas Corporation advertised a Cabinet Gas Range for 145 pesos less 10 percent for cash purchase or easy installment; an Electrolux refrigerator for 390 pesos cash or 440 pesos installment, 15 pesos monthly. The American Hardware & Plumbing Company in Echague, Manila offered Hotpoint electric ranges as “the cleanest and most satisfactory method of cooking and baking” and Red Star Oil Stove that used kerosene, gasoline, or alcohol. T. J. Wolff & Co. in P. Moraga, Manila offered Perfection Petroleum Stoves with ovens from 18 to 65 pesos. Gas and electric refrigerators were available; Servel sold electric refrigerators.

“Dirty” kitchen

Today, many middle-class Filipino homes have two kitchens: one “clean” that displays imported silverware and tableware sets. It is also a showcase for the latest airfryers, blenders, and espresso machines; the “dirty” kitchen serves as the working kitchen where preparation, grilling, and cooking takes place, mostly by household help. In Indonesia and Thailand, the same dual-kitchen practice persists to this day. Long live the “dirty” kitchen!