GOVERNMENT is pushing through with plans to parcel out the controversial gold rush site in Diwalwal, Compostela Valley province to various foreign mining companies, despite the tangle of unresolved legal issues that are threatening to fuel a potentially explosive situation.

On Oct. 14, government accepted letters of intent from mining firms to develop the Upper Ulip-Paraiso portion of Diwalwal consisting of 1,600 hectares. On top of this, there is an existing Memorandum of Understanding between the government and the Chinese firm Zhongxing Technology Equipment (ZTE) to explore and mine a still undisclosed part of Diwalwal.

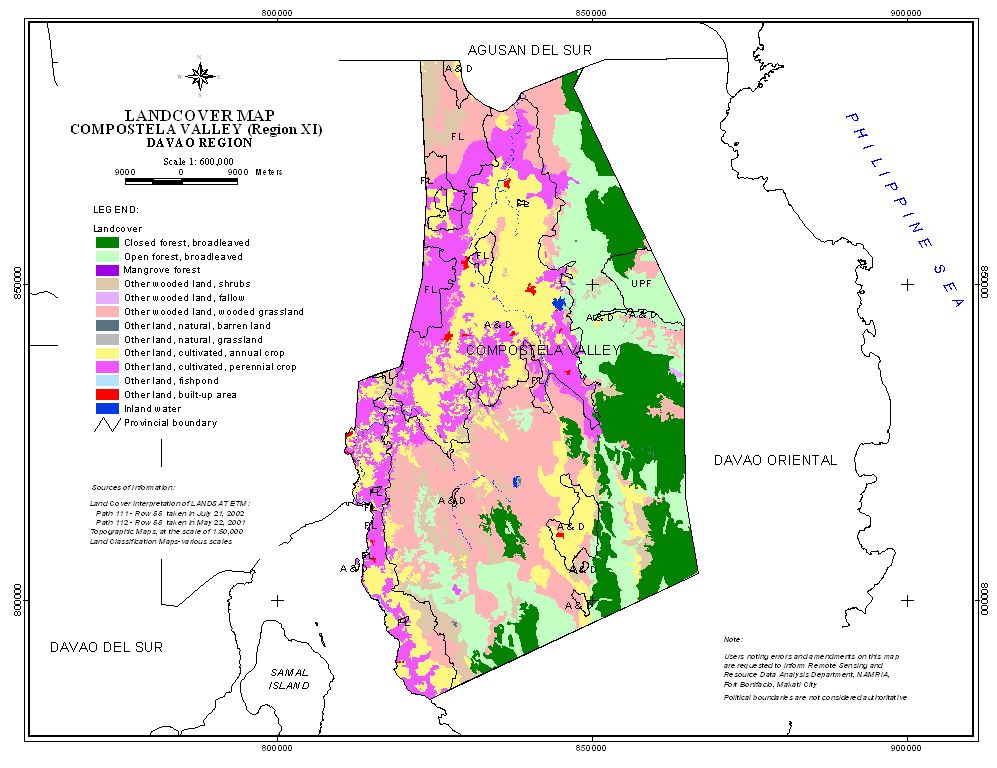

But the 8,100-hectare gold rush area is part of a forest reserve and contains ancestral domains and mining claims that have been in existence long before the government took over the area. Some of these claims overlap and are the subject of court cases. As a result, claimants say, the government is flouting legal processes by entering into agreements or bidding out the gold rush site.

But the 8,100-hectare gold rush area is part of a forest reserve and contains ancestral domains and mining claims that have been in existence long before the government took over the area. Some of these claims overlap and are the subject of court cases. As a result, claimants say, the government is flouting legal processes by entering into agreements or bidding out the gold rush site.

The Diwalwal issue is in fact one of the reasons cited in a new impeachment complaint filed against President Gloria Macapagal Arroyo. The complaint, the fourth since she assumed the presidency, accuses her of betraying public trust by signing an MOU with the controversial firm ZTE.

Among those contesting government’s Diwalwal development projects are the Paper Industries Corp. of the Philippines (PICOP), the Southeast Mindanao Gold Mining Corp. (SEM) and thousands of small-scale miners who have existing service contracts with the Department of Environment and Natural Resources (DENR).

PICOP says some Diwalwal areas are not government’s to bid out. The company is referring to the forest reserve that includes the Diwalwal area that has been in its care since the 1950s. The DENR, however, refuses to recognize PICOP’s jurisdiction, saying the company’s Timber Licensing Agreement (TLA) has already expired.

SEM, on the other hand, is a domestic subsidiary of Marcopper Mining and lays claim to more than 4,000 hectares that straddle the towns of Monkayo, Davao del Norte and Cateel in Davao Oriental. That claim is being challenged by small-scale miners and has reached the Supreme Court. But in July 2006, government entered into a mineral exploration agreement with ZTE over the SEM area, even if only the first division of the Supreme Court ruled against SEM’s claim and the Supreme Court has yet to vote en banc on the matter. The decision, in effect, is not yet final.

SEM, on the other hand, is a domestic subsidiary of Marcopper Mining and lays claim to more than 4,000 hectares that straddle the towns of Monkayo, Davao del Norte and Cateel in Davao Oriental. That claim is being challenged by small-scale miners and has reached the Supreme Court. But in July 2006, government entered into a mineral exploration agreement with ZTE over the SEM area, even if only the first division of the Supreme Court ruled against SEM’s claim and the Supreme Court has yet to vote en banc on the matter. The decision, in effect, is not yet final.

Small-scale miners, meanwhile, were on the brink of eviction from Diwalwal when last year, government announced it was bidding out 729 hectares set aside for their use. Bidding was cancelled at the last minute, but the miners are jittery that large companies might come in any time as government pushes ahead with its mining program.

Revitalizing the mining industry counts among Arroyo’s priority concerns. Former environment secretary Heherson Alvarez has said that Arroyo looks at the mining industry as the Philippines’ ticket to the First World. He has said the government aims to turn the country into a world mining leader by 2010, and a First World country by 2020.

Diwalwal plays a crucial role in the scheme of things. Its gold veins alone are estimated to yield more than two million metric tons. The DENR’s Mines and Geosciences Bureau lists the Diwalwal Direct State Development Project as a second-tier priority mineral site. It is awaiting investors and is targeted for commercial operations by 2009, if funding comes in as scheduled. Last year, the government divided the Diwalwal gold rush site into various prospects for funding by foreign investors.

Not all that glitters

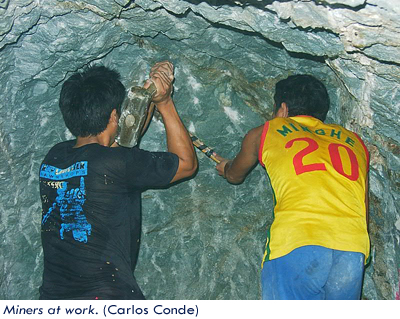

The entry of foreign investors is supposed to be government’s way of putting some semblance of order into Diwalwal. Since the early 1980s, Diwalwal has been known as a wild frontier town, a free-for-all place where fortune hunters from all over the country could come and dig for gold.

But the unregulated mining eventually led to violence. Peace and order problems emerged. Indigenous groups laying ancestral claim to the land clashed with mining corporations that invested large amounts of capital to exploit the earth. Armed groups roamed the gold rush areas to protect the interests of those who found mining operations extremely profitable.

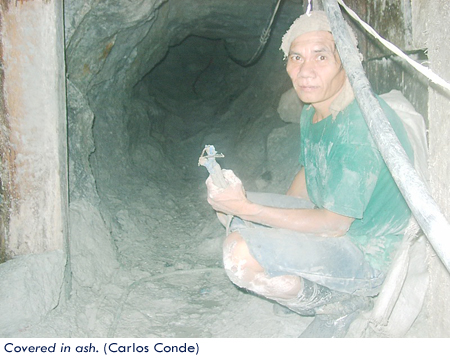

Pollution became a deadly problem as well, with waterways contaminated by mercury used to extract gold from ore. Within a short time, pollution became serious enough to pose a health hazard among residents.

Government cited the chaos in Diwalwal to justify taking over the gold rush site.

On Aug. 12, 2002, Alvarez, then environment secretary, issued Department Administrative Order (DAO) 18, “declaring an emergency situation in the Diwalwal gold rush area and providing for interim guidelines to address the critical environmental and social consequences therein.”

On Aug. 12, 2002, Alvarez, then environment secretary, issued Department Administrative Order (DAO) 18, “declaring an emergency situation in the Diwalwal gold rush area and providing for interim guidelines to address the critical environmental and social consequences therein.”

The order cited the “elevated levels of mercury and serious siltation” as well as peace and order problems, “notably the killing of a judge in Compostela Valley, the alleged burning of tires and toxic chemicals in the underground working areas causing the suffocation of 44 miners and one fatality, the blockade of vital Bincungan Bridge in Davao del Norte and Tagmanok Bridge in Compostela Valley, and fatal ambuscades” as justification for “immediate positive action by government.”

DAO 18 also ordered mining operators to cease activities until they could get the necessary permits. It also deputized the Philippine National Police and the Armed Forces of the Philippines to police all mining activities.

The order also appointed the government-owned Natural Resources Mining Development Corp. (now the Philippine Mining Development Corp.) to plan, manage and implement mining-related activities in Diwalwal.

Three months after Alvarez issued DAO 18, Arroyo signed Proclamation No. 297, which carved out “a certain parcel of land located in Monkayo, Compostela Valley” and proclaimed it a mineral reservation. But the area set aside, 8,100 hectares, was located within the Agusan del Sur-Davao Oriential-Surigao del Sur Forest Reserve, a reserve that had been established during the American colonial occupation way back in 1931.

The PICOP claim

A total of 75,545 hectares of that forest reserve was covered by a TLA granted in 1952 to Bislig Bay Lumber Co. Inc., PICOP’s predecessor. With the signing of Proclamataion 297, PICOP was up in arms.

PICOP says carving out mineral reserves from forestlands is unconstitutional and illegal. The company cites Article 12, Section 4 of the 1987 Constitution, that says “forest lands and national parks shall be conserved and may not be increased or diminished except by law.” A presidential proclamation was not enough. Under Republic Act 3092, only Congress has the power to reclassify any portion of a forest reserve.

Back in 1966, then President Ferdinand Marcos invoked this law when he rescinded an earlier proclamation signed by his predecessor Diosdado Macapagal. Macapagal’s proclamation excluded certain lots from a forest reserve in Cebu but Marcos overturned it because Congress had not concurred with Macapagal’s order.

Today, critics of Arroyo’s Proclamation 297 are citing the same reason. For years, PICOP has been harvesting wood from the forest reserve on the strength of the TLA it got in 1952. The 25-year TLA was renewed in 1977 and was due to expire again in 2002. Years before the expiration date, PICOP claimed it had complied with the paper work necessary to convert the TLA into an IFMA or an Integrated Forest Management Agreement.

Alvarez had promised to sign the IFMA renewing PICOP’s concession area but he dilly-dallied and when he did sign it, he had reduced PICOP’s concession area by 40,000 hectares. Contesting the government’s claims, PICOP took its case to court. The company won in the Quezon City Regional Trial Court and the Court of Appeals, which have asked the DENR to restore the concession area. The DENR has refused to do so.

The company, however, lost its case in the Supreme Court which upheld on Nov. 29, 2006, the DENR’s claim that PICOP had failed to comply with the requirements needed for an IFMA. These requirements included payment of forest charges and other fees due the government, a clearance from the National Commission for Indigenous Peoples, and permission from all the affected local governments in the area.

PICOP, however, continues its legal battle against Proclamation no. 297. The case is still pending with a Quezon City regional trial court. Part of PICOP’s concession area is now within the 8,100-hectare Diwalwal project.

The Marcoppper/SEM claim

In March 1986, Marcopper acquired a two-year exploration permit, EP No. 133. It has since then been besieged by conflicting mining claims from other groups. Small-scale miners began proliferating in the area after then DENR Secretary Fulgencio Factoran Jr. issued Department Administrative Order (DAO) No. 66 declaring 729 hectares of the areas covered by Marcopper’s EP 133 as nonforest lands and open to small-scale mining.

In March 1986, Marcopper acquired a two-year exploration permit, EP No. 133. It has since then been besieged by conflicting mining claims from other groups. Small-scale miners began proliferating in the area after then DENR Secretary Fulgencio Factoran Jr. issued Department Administrative Order (DAO) No. 66 declaring 729 hectares of the areas covered by Marcopper’s EP 133 as nonforest lands and open to small-scale mining.

In its request for the extension of its EP, Marcopper cited the legal cases and trouble with small miners for its failure to complete its work program. It was able to extend its permit until July 6, 1994.

Marcopper said it did not find it necessary to seek further extension of its EP because it had assigned its rights and interests on the area to its domestic subsidiary, Southeast Mindanao Gold Mining Corp.

SEM by then had applied for its own Mineral Production Sharing Agreement (MPSA). The MPSA covers all mining activities from exploration to production. It was granted in October 1995 over the opposition of several mining groups.

One oppositor said that since Marcopper’s permit has expired and has become irrelevant to the case, there is no more legal basis to give due course to SEM’s application for an MPSA.

SEM replied that what it obtained from Marcopper was not the latter’s EP 133, which was about to expire at that time, but its mining rights which “include entitlements to the minerals which ripen into a property right.”

SEM’s competitors in Mt. Diwalwal took the case to the CA which upheld SEM’s claim. Strangely, the court’s basis for the decision was still EP 133.

Dissatisfied by the decision of the CA, Rosendo Villaflor and the Balite Communal Portal Mining Cooperative went to the Supreme Court. So did SEM which wanted to recover 729 hectares that were excluded by DAO-66 from the coverage of EP 133.

Another mining firm, Apex Mining Corp., justified its petition to intervene in the case, saying that it was already present in Diwalwal even before Marcopper and SEM started operating there.

On June 23, 2006, a decision by the Supreme Court First Division penned by Justice Minita Chico-Nazario declared as illegal the transfer by Marcopper of its EP 133 to SEM.

“With the expiration of EP 133 on July 6, 1994, Marcopper lost any right to the Diwalwal Gold Rush Area. SEM, on the other hand, has not acquired any right to the said area because the transfer of EP 133 in its favor is invalid. Hence, both Marcopper and SEM have not acquired any vested right over the 4,941.6759 hectares which used to be covered by EP 133,” the decision said.

The Nazario decision also invalidated DAO-66, saying the DENR secretary has no power to convert forest reserves into non-forest reserves. The 729 hectares that DAO-66 reserved for small-scale mining operations was returned to the area covered by what used to be Marcopper’s EP 133.

But with the issuance of Proclamation 297 and the declaration of an emergency situation in Mt. Diwalwal, the high court decision said that “mining operations in the Diwalwal Mineral Reservation are now therefore within the full control of the state through the executive branch.”

It further declared that the “State can either directly undertake the exploration, development and utilization of the area or it can enter into agreements with qualified entities.”

SEM says that Nazario’s decision is not final executory, and that only a Supreme Court decision voted upon in a Court’s en banc session can put it into force.

The ZTE connection

On July 12, 2006, less than three weeks after Nazario’s decision and even without the Supreme Court deciding en banc, the Arroyo the government signed a Memorandum of Understanding with ZTE International Investment Ltd., ZTE Corp.’s international arm, for the exploration, development and operation of mining areas in Diwalwal.

Trade and Industry Secretary Peter Favila signed in behalf of the Philippine government while Yu Yong, president of ZTE International, signed for the Chinese firm. Signing as witnesses were Michael T. Defensor, then the presidential chief of staff and a former environment secretary, and Hou Weigui, chairman of ZTE Corp.

ZTE figured in a controversy early this year for entering into a deal for a national broadband network. Although Arroyo has cancelled the broadband deal, the mining agreement remains.

Mining claimants are perplexed by the entry of ZTE into mining. Minutes of a July 2006 meeting between ZTE and DENR officials over a mining project in North Davao show both parties agreeing that “ZTE International is an investment company and is not competent to handle the exploration, development and operation of a mine.”

In that meeting, the two parties also said ZTE’s participation would have to come in the form of government-to-government agreement, “otherwise ZTE would have to go through the usual process which is either through bidding or through the ‘unsolicited proposal’ subject to Swiss challenge.”

Mining claimants fear that this is what will happen in the Diwalwal project. Already, small-scale miners fear government is short-circuiting the process because it entered into an MOU with ZTE despite a final decision being awarded from the Supreme Court.

Mining claimants fear that this is what will happen in the Diwalwal project. Already, small-scale miners fear government is short-circuiting the process because it entered into an MOU with ZTE despite a final decision being awarded from the Supreme Court.

On March 24, 2008, Melchor Plaza, chairman of Balite Integrated Small-Scale Miners Cooperative (BISSMICO), wrote Chief Justice Reynato Puno and Justices Minita Chico-Nazario and Consuelo Ynares-Santiago to express his concern over Favila’s revelation at the Senate that government had entered into a mining agreement with ZTE.

Plaza said: “Pag pinagdugtong at sinuri po, paano naipagkasundo ni Secretary Favila ang Mt. Diwalwal sa ZTE/China kung nililitis pa ng korte kung sino sa magkatunggali ang may karapatan sa Mt. Diwalwal (If you put together and examine [the events], how could Secretary Favila commit Mt. Diwalwal to ZTE/China when the court has not decided with finality who among the claimants has the right over Mt. Diwalwal)?”

He stressed that the issue of who has the right to develop Mt. Diwalwal is still pending in the Supreme Court.

“Sa aming simpleng pag-iisip, naipagkasundo lamang ni Favila ang Mt. Diwalwal kung alam po niya ang magiging final decision ng Korte (In our simple minds, Favila could enter into an agreement on Mt. Diwalwal only if he knew that the court’s decision would become final),” Plaza said.