Long before the internet and social media, the ritual of traveling overseas included sending postcards with a short message to friends and family. The postcard usually features a famous landmark that screamed “I was there!”

In many ways, the postcard is the equivalent of today’s ubiquitous selfies, as one’s own visual souvenir, so portable and easy to send to the rest of the digital world.

The Ortigas Foundation Library presents an exhibit titled Early Philippine Picture Postcards 1900-1930s until August 10, 2025. Its address: 2nd Floor, McKinley Parking Bldg., Greenhills, San Juan (above Unimart).

The exhibit is divided into seven sections of postcard imagery, such as:

Private Mailing Cards: One of the first examples of picture postcards, 1898-1901. The message and the image were required to be on one side; the address was on the reverse.

Filipinas in Traditional Attire from Mindanao to the Cordilleras 1900s-1910s. Demure women in baro’t saya as everyday wear all over the country and indigenous women dressed in their own handwoven attires.

Panorama Picture Postcards. Shot with a wide angle lens, the elongated cards were printed on two or three postcard mounts that are joined together. Rarely mailed, they are usually kept as a souvenir of travel.

Some panorama postcards depict the Walled City or Intramuros, Fort Santiago, Luneta Park, Pasig River, Baguio’s Camp John Hay, Burnham Park, and government offices.

In other panorama postcards, the original photographs were black-and-white; color plates were added after the first printing sometimes by Japanese or German artist.

Studio Portrait Postcards 1910s-1930s: Getting one’s portrait in a studio became a must-do in those days. The results were sepia-toned photographic portraits mounted with postcard backs so that they could be mailed as souvenirs.

Everyone one went to the studio, from children to grandparents; the studio provided a range of costumes and props to satisfy one’s fantasy and desire, with people posing in romantic and exotic settings. Geishas in kimonos, a princess, a proper and rich-looking gentleman in white suits and leather shoes, a soldier or a navy man, a Hindu prince or a maharajah.

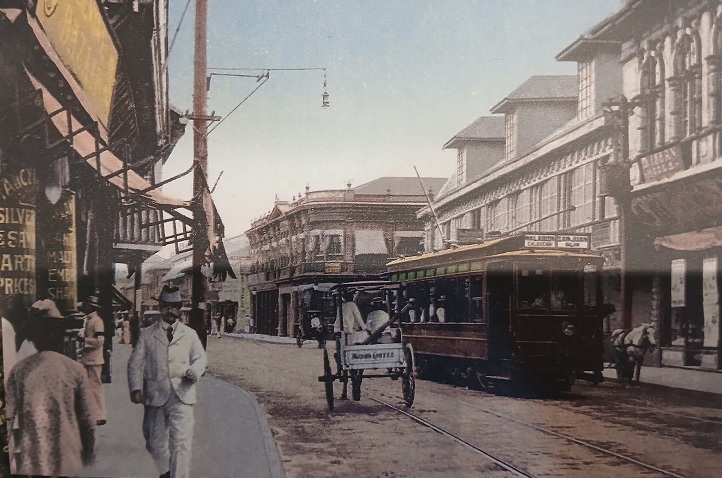

Manila Views: Aside from Luneta or Intramuros views, notable postcards include Bilipid Prison Marching Band, Manila, a scene that is contrary of our image of Bilibid Prison nowadays as a place of corruption with powerful prisoners lording it all; the era of horse-drawn carts as a means of transportation in Manila, Catamata Caramata Manila, 1910s; and the postcard of P. Burgos St. Fashionable Drive speaks of a vanished Manila where one can enjoy a leisurely drive around town.

Likewise, when one sees turn-of-the-century images of old Manila such as the Binondo Church, Old Parian Wall to Intramuros, Botanical Garden, and Carriedo Fountain in Plaza Avelino, Manila—one can almost understand why Manila was called the “Pearl of the Orient” with its wide and quiet streets, clean air, American colonial buildings, and pleasant surroundings. After the war, that Manila no longer exists.

Provincial Views: Postcards depict Zamboanga, Cebu, Bacolod, Cebu, and Dumaguete and show places of interest such as the Old Bell Tower, Dumaguete; Calle Colon in Cebu as the oldest street in the country; typical Manobo houses in Davao; the main street of San Mateo in Butuan; old churches in Cebu and Butuan; and river scenes of the Rio Grande in Mindanao.

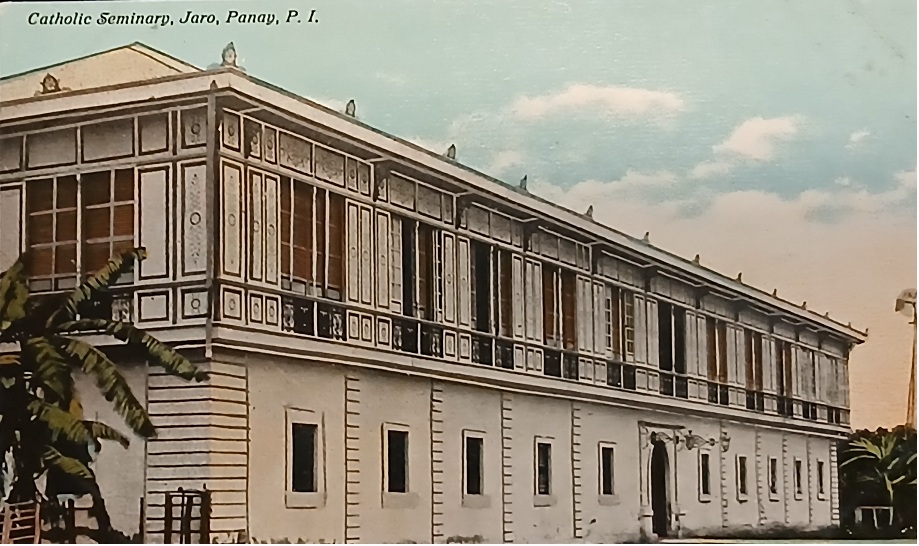

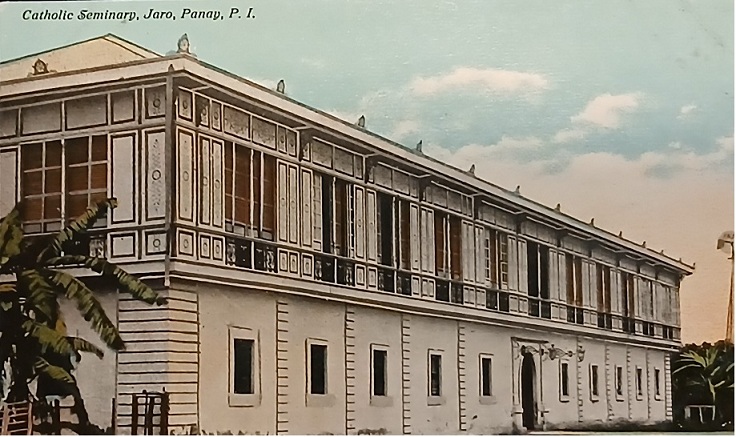

Pier scenes depict a mail steamer named “Cebu” in Cebu, pier landing in Iloilo, and Capiz Harbor, (now Roxas City) in Panay. Old Iloilo scenes include Calle Iznart, Iloilo City and the Catholic Seminary of Jaro or the Seminary of Saint Vincent Ferrer founded in 1869, the fifth seminary and the last one founded under the Spanish regime.

Many postcards of forts and American military camps were printed such as a Spanish fortress in Zamboanga (Fort Pilar), Camp Keithley in Marawi, and Camp Overton in Iligan City; the last two were American military camps in Mindanao in the early 1900s that housed American troops during the Philippine-American War (1899-1902). Today, a steel manufacturing company occupies the site of Camp Overton.

Another postcard shows Fort William Mckinley, Rizal described as “the largest occupied and the most completely outfitted military post in the world” established during the Philippine-American War. In 1949, it was turned over to the Philippine Government and renamed Fort Andres Bonifacio as the headquarters of the Philippine Army. Today, it is the site of Bonfacio Global City.

Likewise, the country’s early postcards reveal historical realities behind such “picturesque” images: American military camps used to subjugate Filipinos in their quest for independence; many postcards depict stereotyped and racist views of the indigenous peoples of the Philippines, as “savages” and “uncivilized,” and used to justify America’s “manifest destiny” in its first colony in the Far East.

Invaluable record

Under American colonial rule (1898-1946), the use of postcards increased significantly amidst the arrival of American military personnel, administrators, and teachers in the country. As Jonathan Best, the author of Philippine Picture Postcards,1900-1920 (1994) describes our early postcards as “an invaluable record of the life and time of the Filipinos just after the turn of the century up to the war.”