Much online and printed prose has been written about Rolando E. Peña’s greatness as a geologist and as a revolutionary. But according to another geologist and his friend from childhood Noe Caagusan, little has been said about his reputation as a “circumstantial lover.”

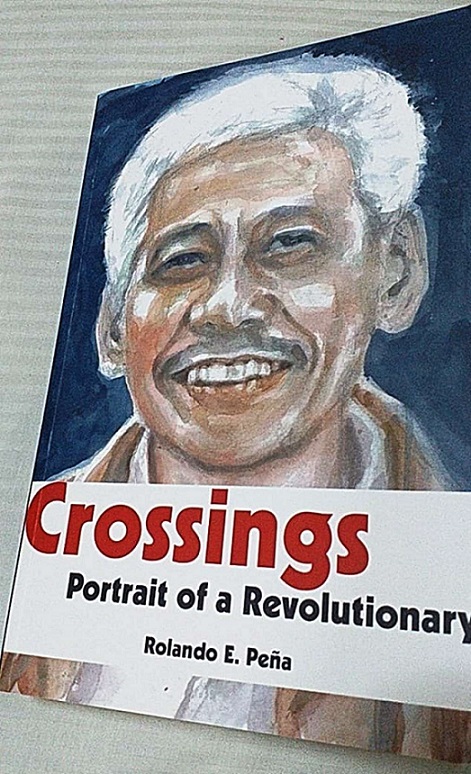

At the posthumous launching of Peña’s memoir Crossings: Portrait of a Revolutionary, published by the Association of Filipinos for the Advancement of Geoscience Inc. of which the author was a founding member, held at the University Hotel, UP Diliman, Caagusan described the context from which he was speaking.

In the ’50s and ’60s when he and Peña were geology majors at UP, the Philippines banned what were deemed to be pornographic literature: D.H. Lawrence’s Lady Chatterley’s Lover and John Cleland’s Fanny Hill. Learned people like the two friends asked people who came from overseas if they had copies of those erotic novels.

In a way, these shaped Peña’s account of his love affairs which are chronicled in the book in a tasteful manner. His honesty reflects a boldness in writing that cannot be gleaned from grim and determined accounts of underground lives. Caagusan was quick to defend his friend as one who respected women and was in fact that rare man—a feminist.

Poet Marra Pl. Lanot agreed. In her tribute, she wrote how Peña was the quiet type like background music and yet, he knew his way around women. “Maybe girls found him attractive because he was sweet and gentle in his manner and speech. He was like the way he walked—slowly, leisurely, unhurriedly. Furthermore, he was supportive of women and of women’s rights.”

Lest we reveal spoilers about the romantic interludes in Peña’s life, it is best for the reader to get hold of a copy of the memoir launched on the first anniversary of his death on National Heroes’ Day with a crowd of activists who looked like they were willing to fight another day.

Sibyl Jade R. Peña, the author’s daughter

But it isn’t just curiosity about the prurient details that will motivate one to go through the 370 pages of the book. In the chapter on “Years of Living Dangerously,” there are two vital historical narratives written in the first person about the planning and implementation of the arms smuggling done by the Communist Party of the Philippines. Peña virtually captained the ships mv Karagatan followed by mv Andrea. Although the smuggling attempts were aborted, political scientist Francisco Nemenzo Jr. praised “the raw courage of those who risked their lives for a forlorn people’s war.”

The same book carries samples of translation work that Peña indulged in in his spare time. He translated from English to Filipino Pablo Neruda’s “Ode to Tomatoes,” from Spanish to Filipino the Sandinista poet Giaconda Belli’s “Mi Amore es Como un Rio Caudaloso” and the anonymous 36 Strategems from Chinese to English.

Truly these works of love are indications of the brilliant mind of the self-effacing translator who was facile in several languages. One grieves at the amount of literature that could have continued to spill out of him if death had not overtaken him.

According to his surviving child, Sibyl Jade R. Peña, the contents of the book are divided into the pre-martial law years (“Calm Before the Storm”) to include her father’s account of how professionally edited UG publications like Ang Bayan and Liberation (a name he thought of) came to be, the second part taken up by participatory accounts of the Karagatan and Andrea debacles, the latter stranding him in China for seven years at the height of the Cultural Revolution.

When the Armed Forces pursued Peña and his comrades through the Sierra Madre forests, the memoir reads like thriller that can’t be put down. One wouldn’t be surprised if film rights for the Karagatan and Andrea portions will be sought in the near future.

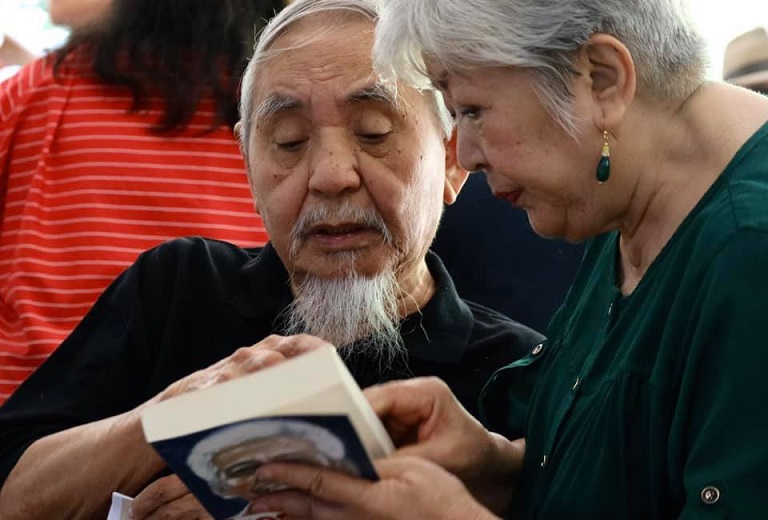

Francisco and Princess Nemenzo browsing through a copy of the memoir.

The third part consists of correspondences, mainly with his daughter, showing “how he was as a father, his unfiltered thoughts and his travel notes.”

The fourth part is made up of tributes, in prose and poetry, from Peña’s wide sphere of influence—geologists, geology majors, visual and performing artists, social activists, etc.

There is a folio of photographs showing Peña with family, friends, colleagues, including the Philippine team that defended the Philippines’ claim on Benham Rise at the United Nations Convention on the Laws of the Seas in 2011. It is just as well that Peña did not live long enough to see China’s encroachment on the country’s maritime territory.

Crossings deserves a prominent place on the shelf of martial law literature. Peña continues to live in word and in spirit.

Copies of the book will soon be available at the Bantayog ng mga Bayani on Quezon Ave., Quezon City, Popular Bookstore on Morato Ave., QC, Solidaridad Bookshop on Padre Faura, Ermita, and Mt. Cloud Bookshop on Yangco St., Baguio City.