The reality that eight out of 10 Filipino children experience physical, verbal and sexual violence, mostly in places where they expect to be protected such as the home and school, remains a serious concern, prompting a group of children to seek government help.

“Do something about it now,” the group implored President Rodrigo Duterte in a manifesto issued at the end of a consultation on April 7, where findings of the National Baseline Study on Violence against Children in the Philippines were presented to them.

The study, completed in 2016, notes a culture of silence around issues of violence against children and lack of support for those who want to tell adults about their experience.

“The survey represents what children and young people experience in the home, school and community; there is corporal punishment, physical and sexual abuse, discrimination and bullying,” said the group of 15 children aged nine to 17.

Members of the group are from schools in the National Capital Region, Visayas and Mindanao, who are among the regular spokespersons on children’s issues trained by organizations such as UNICEF, the Council for the Welfare of Children (CWC), and ChildFund Philippines, which organized the consultation.

Ruth Limson-Marayag, planning officer of CWC, who presented the survey results to the group, said while the CWC and other organizations continue to empower children, there is a lack of support for children who want to tell adults and persons responsible for them about their experiences of violence.

Ruth Limson-Marayag of the Council for the Welfare of Children present the study on violence against children. (Photo by Diana G. Mendoza)

“Because of the lack of support and services for children, they are reluctant to speak beyond telling their fellow children or friends,” she said.

The CWC completed the five-year study in 2016 in partnership with UNICEF, and results were presented to the public that year. The study found that violence is experienced by eight out of 10 children mostly in their homes, and also in their schools.

Inputs from the children’s consultation will be incorporated in the Philippine Plan of Action to End Violence against Children to be launched next month by the same organizations that will ask government and non-government agencies working for children to come up with their own commitments to action.

In their manifesto, the children asked Congress to pass the bill on positive discipline, for government to strengthen and make functional the barangay council for the protection of children (BCPC), implement and monitor child protection policies in schools, install a reporting and referral mechanism and establish facilities for children who experience violence.

“Kami po ay nananawagan sa pamahalaan na huwag ibaba ang age of criminal responsibility,” the children also stated in their manifesto, referring to the move of Duterte and his political allies to support a bill that would lower the age of criminal responsibility from 15 to 9. Instead of supporting this move, the children said the government should strengthen the campaign and advocacy to prevent violence against children (VAC).

The Positive Discipline of Children Act of 2017 that prohibits all forms of corporal or humiliating or degrading punishment on children and promoting positive or non-violent forms of discipline is pending approval in the Senate.

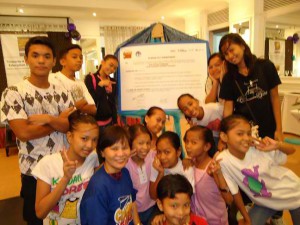

Children present their manifesto with the stop violence sign. (Photo by Diana G. Mendoza)

Children present their manifesto with the stop violence sign. (Photo by Diana G. Mendoza)

The BCPC, created under the Child Welfare Code under Article 87 of P.D. 603, mandates every barangay to establish the council and foster learning opportunities, safe environment and good relationships between children and their parents, other elders and peers in their communities to ensure the protection of children.

According to the baseline study, the children’s reluctance to speak is linked to the lack of support services, shaming of survivors and weak law enforcement. “In the cases of street-involved children and children in conflict with the law, the role of law enforcement as a perpetrator of violence creates a confluence of drivers for the perpetuation of exploitation and violence against children in the community,” the study said.

Eight of 10 children and young people aged 13-24 years have experienced some form of violence in their lifetime, whether in the home, school, workplace, community or during dating, the study noted. “Thousands of children are robbed of their childhood and suffer lifelong developmental challenges as a result of violence. Impacts include mental and physical health disorders, anxiety, depression and health-risk behaviors including smoking, alcoholism, drug abuse and engagement in high risk sexual activity.”

The study, accompanied and supported by a systematic literature review of the drivers of violence against children, marked a watershed moment in the efforts to address VAC and is vital in putting a clearer and more accurate picture of the extent and magnitude of violence against Filipino children and youth.

A total of 3,866 children and youth aged 13-24 years from 172 barangays in 17 regions of the country participated in the survey. About 2,303 belonged to the 13- <18 years age group. Males experience violence more than females, 81.5% against 78.4% among females. About 78.8% of children aged 13-<18 years encountered violent experiences compared with 80.9% in the older group.

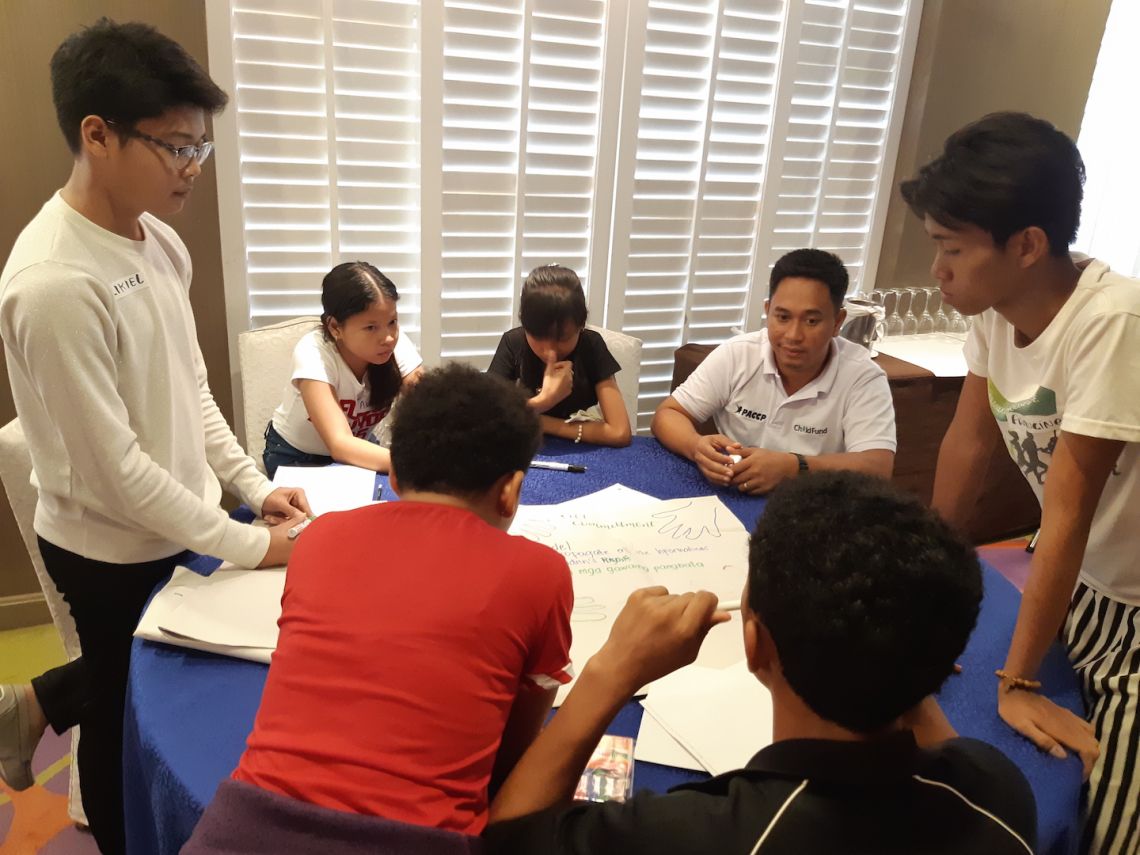

Children create their presentations with Dondon Datayan, program officer of ChildFund Philippines. (Photo by Diana G. Mendoza)

Children create their presentations with Dondon Datayan, program officer of ChildFund Philippines. (Photo by Diana G. Mendoza)

The study said there is robust data on the nature of intergenerational violence in the Philippines – “that violence often begins at home and impacts on violence in other settings and relationships.”

In the children’s consultation, the young participants reacted strongly to violence committed by parents and teachers. “They should respect children the way they teach us how to show respect,” said one of the children.

In the home, alcohol misuse is a significant risk factor that triggers violence, the study pointed out. Experiencing childhood or familial sexual violence and experiencing or being exposed to violence in the home increases the risk that children will use or experience violence against partners, peers and family members.

Violent discipline is the most frequent form in the home, according to the study, driven by social norms around the use of and effectiveness of discipline, authoritarian parenting and the parents’ levels of education. Parental histories of physical abuse when they were growing up combined with financial stress and substance misuse create a ‘toxic trio’ of risk factors for physical violence in the home.

Sexual violence occurs in single-headed households and those with absent parents with lack of supervision, it added. Migration, a significant driver of absentee parenting, increases children’s risk of exposure to sexual violence at home.

Emotional violence from parents increases children’s negative behavior, which in turn increases their risk of experiencing violent discipline and perpetrating aggressive behavior towards others, the study noted. Parenting practices such as coercion, threats, insults and a frightening tone increase the risk of child maltreatment and trigger similar behavioral patterns in parent/ child and other relationships.

Physical violence, the most prevalent form, is often perpetrated by adults, with verbal violence as the second most frequent. This is driven by social norms around the use of corporal punishment in school and at home.

Sexual harassment is the most frequent form of sexual violence in school settings, occurring in both primary and secondary schools, with girls being particularly vulnerable. Grey literature has also highlighted that lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender (LGBT) youth may be particularly at risk of sexual violence at school, and often from peers.

Since 2007, more than 20 countries including the Philippines, have undertaken national surveys on violence against children, contributing greater evidence and global and regional understanding of research on this issue. Starting in 2010, the Philippines committed to undertake its own national study – the first country in the Asia Pacific region to do so.

The study said Philippine laws and policies enacted recently were crafted to better protect children and adhere to international standards, and are thus held up as positive examples for the region. In spite of these laws, a dearth of national data and a lack of reporting mechanisms have rendered many less effective than intended.