AT the corner of a gallery at the Lopez Museum hangs a painting measuring 18 inches wide and 24 inches high. It is over a century old, but the political issue depicted remains just as relevant today with the threat to freedom of expression embodied in the Cybercrime Prevention law.

Commissioned by the US government, the painting is one of several studies done by Félix Resurrección Hidalgo, one of two celebrated Filipino artists of the time, the other being the more famous Juan Luna.

It illustrates the Philippines symbolized by a Malay woman holding a bolo pointing downward. With her other hand she offers an olive branch, a sign of surrender, to a Joan of Arc-like maiden, symbolizing the United States. Its message was that the Philippines needed the benison of US colonial rule.

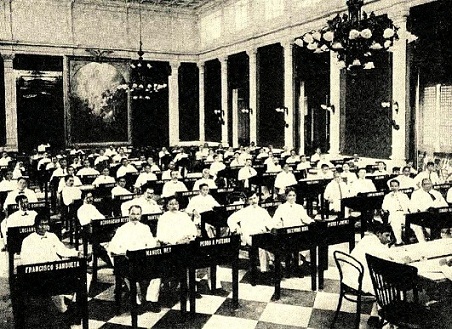

The final product, “Per Pacem et Libertatem” (“For Peace and Liberty” in Latin), made its debut at the 1904 Saint Louis Exposition in the United States. It later graced the legislative hall of the Ayuntamiento building in Intramuros, home of the Philippine Assembly. The legislature was formed by the American colonial government in 1907 to allow the Filipinos limited self-rule under US tutelage.

The painting was destroyed in the 1945 Battle of Manila in World War II, which left the Ayuntamiento a burnt out shell. It now only exists in historical photos.

At the time the painting was commissioned, US public opinion was split on the issue of whether or not the United States should annex the Philippines. In 1898, US forces had defeated Spanish forces in the islands following the outbreak of the Spanish-American War.

Filled with missionary zeal, US President William McKinley opined that it would be “dishonorable” to return the islands to Spain or leave them open to other world powers. Moreover, he reasoned, the Filipinos “were unfit for self-government [and] would soon have anarchy and misrule”. The only option was to “educate the Filipinos, and uplift and Christianize them” under a policy of “benevolent assimilation”.

However, in the eyes of Filipino revolutionaries who rose up against Spanish colonial rule, America was quelling an independence movement that was no different from the American Revolution.

Apolinario Mabini, the Philippines’ first prime minister and foreign affairs minister, predicted a confrontation between the Filipinos and the Americans: “The conflict is coming sooner or later, and we shall gain nothing by asking as favors of them what are really our rights.”

Finally, on February 4, 1899, war erupted. It went down in history books as the Philippine-American War, which lasted officially until 1902.

Mabini later explained why war was the Filipinos’ only option when their independence aspirations were ignored by Washington. “If we surrendered unconditionally, leaving our political fate at its mercy, the Americans would no longer have any doubts about our unfitness because, by not defending our freedom, we would be showing our little understanding and love for it,” he stated in his 1903 manifesto La Revolucion Filipina. “We had therefore to choose between war and the charge of unfitness.”

Mabini later explained why war was the Filipinos’ only option when their independence aspirations were ignored by Washington. “If we surrendered unconditionally, leaving our political fate at its mercy, the Americans would no longer have any doubts about our unfitness because, by not defending our freedom, we would be showing our little understanding and love for it,” he stated in his 1903 manifesto La Revolucion Filipina. “We had therefore to choose between war and the charge of unfitness.”

That charge would dog the nation to this day, however, because of the country’s political realities.

America’s first civilian governor in the Philippines, William Howard Taft, early on saw the kind of Filipino political leaders that he had to work with shortly after he took up his post in 1901. They were nothing but “intriguing politicians, without the slightest moral stamina, and nothing but personal interests to gratify.”

The Americans touted the Philippines as Asia’s “showcase of democracy”, but it was a thin veneer. “The United States introduced the Filipinos to democratic institutions without requiring them to respect the substance of democracy,” wrote Stanley Karnow in his Pulitzer Prize-winning book In Our Image: America’s Empire in the Philippines. “Over time, realizing the limitations of their influence, US officials reluctantly accommodated to Filipino traditions.”

Nearly seven decades later, Senator Benigno Aquino Jr., the father of President Benigno Aquino III, summed up the conditions in the country. “The Philippines is a land of traumatic contrasts,” the elder Aquino wrote in the July 1968 edition of Foreign Affairs.

“Here is a land in which a few are spectacularly rich while the masses remain abjectly poor. Here is a land where http://www.ejsmith.com/ freedom and its blessings are a reality for the minority and an illusion for the many,” he lamented. “Here is a land consecrated to democracy but run by an entrenched plutocracy. Here is a land of privilege and rank — a republic dedicated to equality but mired in an archaic system of caste.”

Many Filipinos today complain that not much has changed, at least in the area of democratic reforms.

For one, civil libertarians are contesting a February 18 Supreme Court ruling that declared as constitutional an online libel provision of the newly enacted cybercrime law. Under the law, a person may be sued for libel for opinions expressed on the Internet.

Pro-democracy activists contend that not only did the law violate constitutional guarantees of freedom of speech, it was a throwback to the Marcos dictatorship when dissent was brutally suppressed. Only the rich and powerful would benefit from the law because they could afford to file suits that are only meant to harass critics.

Explaining the dysfunctional democracy, some political observers note that the Philippines is still a young republic. If so, it is a long road ahead to political maturity.