We have been eating tinapay for a long time.

Rice is the staple dish of Philippines a tropical country where wheat does not grow now, and yet there is a tradition of baking and eating bread, biscuits, and pastries made from wheat flour—another culinary legacy from the Spanish past.

(From the 17th century, the Spaniards started planting and harvesting wheat for their own use, in Ilocos, Batangas, Laguna, Panay).

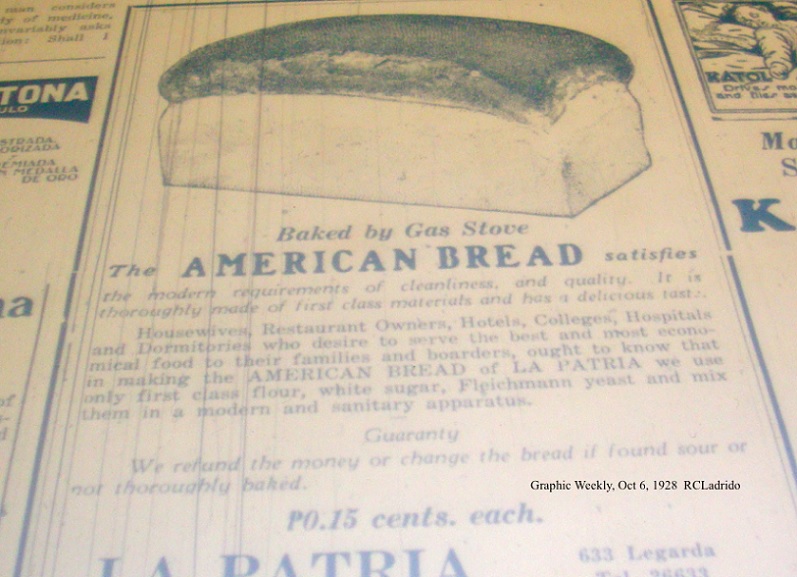

How did tinapay find its way into our hearts and stomachs? Today, Filipinos eat the ubiquitous pan desal and the sliced white bread known as “pan Americano” or “tasty” for breakfast or merienda. Bakeries all over the country sell a wide array of breads, biscuits, and pastries.

Of rice and bread

A Venetian who joined Ferdinand Magellan’s expedition of 1519-1522, Antonio Pigafetta wrote that in an island near Palawan, the king and his people gave them various kinds of food, made “only of rice,” some of which were wrapped in leaves in “longish pieces” and some resembled “sugar loaves” or “tarts with egg and honey.” (The First Voyage Around the World, ca. 1525).

‘Tinapai’

Pigafetta noted that “tinapai” was a term “for certain rice cakes.” His glossary list is the first Western record of Philippine language—Visayan words that are still in use in Samar, Leyte, and Cebu.

‘Tinapai’ evolved to refer to “a kind of cake or loaf made of wheat flour, the size of a chocolate cup saucer.” It also referred to wheat bread in general and to the consecrated host, symbolic of the body of Christ, as part of the Catholic mass. The Church’s Code of Canon Law requires that hosts must only be made of wheat flour and water.

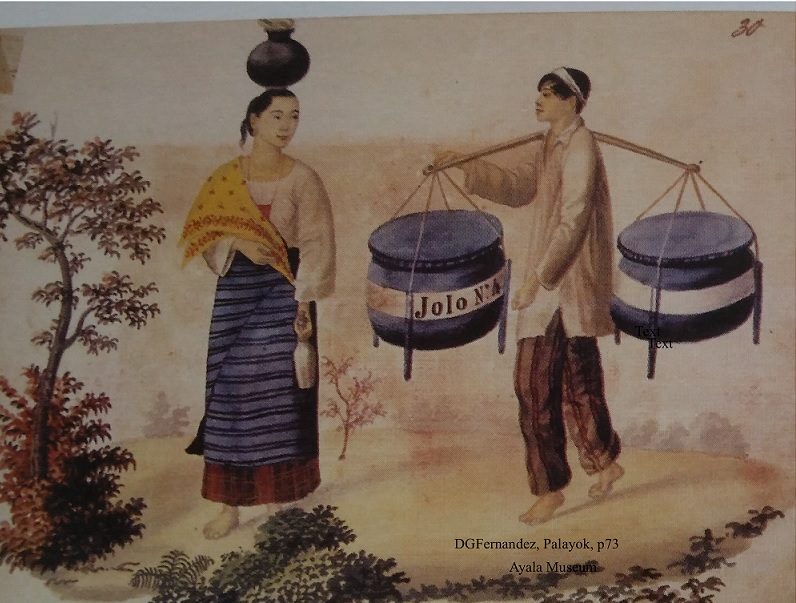

Fr. Juan J. Delgado, a Jesuit priest, in his Historia General Sacro Profana (1751) described the rice cakes as golosinas or sweets and used Spanish names for cookies and pastries for them —broas, marquesotes, or rosquetes.

In E. Arsenio Manuel’s linguistic study of Chinese elements in the Tagalog language (1948), the entry for tinapay:

Tinapay: tau (bean); pia (bread, biscuit, anything made of flour). Bread. Magtinapay, to make bread; magtitinapáy, baker, a vendor of bread..

Wheat flour

The Manila-Acapulco galleon trade (1565-1815) saw the constant need to provision the sailors with a regular supply of sea biscuits or “twice-cooked bread.” Galleons bound for Mexico from Manila carried around 40,000 pounds of sea biscuits for the six-month journey. Magellan’s expedition in 1521 carried some 243,563 pounds of bizcocho in wooden barrels that was supposed to last for six years. (Felice P. Sta Maria, The Governor General’s Kitchen, 2006)

Initially, flour was shipped all the way from Nueva España [Mexico]. It was an expensive way of sourcing flour, and unnecessary, according to a 1619 document addressed to the Spanish king. It added that flour shipped from China and Japan was very cheap, costing 16 reals per quintal; flour from Nueva España [Mexico] and delivered to Manila cost more than “80 reals per quintal.” (Blair & Robertson, 1973)

With extensive Chinese trade long before the arrival of Spain, China became a major source of wheat flour for the islands. Antonio de Morga in his Sucesos de las Islas Filipinas, (1609) reported that 30 to 40 Chinese junks would arrive from China usually in March, all laden with merchandise and supplied the Spaniards with wheat flour and other edibles.

Japanese and Portuguese merchants also arrived every year from the port of Nagasaki, usually at the end of October and March, and their cargo included “excellent wheat flour for the provisioning of Manila.”

The Spread of Bakeries

The Spaniards established the first official bakery in Manila known as the Royal Bakery of Manila to serve their needs. Fernando de Silva, a pro tempore governor general appointed in 1625, granted a favor to Captain Andres Fernandez de Puebla, and to the Manila City government. The bakery was located inside the Spanish Intramuros, near the Parian, the Chinese settlement. Sangleys, familiar with steamed breads in China, were hired as bakers. (Sta. Maria, 2006)

By 1902, there were 322 bakeries all over the Philippines, mostly concentrated in Manila and other urban areas. The 1902 census ranked the baking industry as first by number of establishments, with 39 provinces (including Iloilo) with at least one bakery.

Bakeries were quite profitable; it is the fifth highest in terms of value, based on products sold. A bakery required only an oven and a few bags of flour. In 1902, an average baker earned 25 pesos a month; compared with a foreman who earned 30 pesos. By 1921, there were 23 bakeries listed around Manila and more bakeries were opening in the provinces. (Sta. Maria, 2006)

By the time the French adventurer, Jean Mallat (1806-1863), had settled in Manila in the nineteenth century, eating breads and biscuits was firmly established in the country. Mallat noted that the “Indios of the Philippines have a special talent for that part of cooking that has to do with pastry,” in his book The Philippines, 1846.