Shrinkflation comes inevitably amidst the rising prices of almost everything, including pandesal.

The good news: no flour shortage. The bad news: prices of bread products will keep on rising! This is the gist of Bida Konsyumer’s discussion last July 23, 2022 with three guests from the baking industry: Ricardo Pinca, executive director, Philippine Association of Flour Millers, Inc. (PAFMIL), Johnlu Koa, president, Philippine Baking Industry Group, and Jam Mauleon, director, Asosasyon ng Panaderong Pilipino. (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SnADKlU5Kc0)

Hosted by Alvin Elchico, Bida Konsyumer is a one-hour ABS-CBN Teleradyo program.

Amidst a growing population, the country’s consumption of wheat-based products (mainly bread and noodles) has been surging in recent years. In 2020, the Philippines is the world’s third largest importer of wheat; it is also the world’s second largest importer of U.S. wheat. More than 90 percent of our wheat comes from the U.S.

The country buys two types of wheat: milling wheat in the form of wheat grains, for bread products and feed wheat (mostly from Russia and Ukraine) for livestock and the fisheries.

No flour shortage

Pinca reassured everyone that there is enough supply of flour, and we will not run out of flour.

Four of their vessels unload wheat every month in Manila, Cebu, Batangas, Davao, he says.

Flour prices

Wheat prices have increased in the world market. Pinca cites the Russia-Ukraine war; India has banned wheat export to protect their own market; the ongoing severe drought in the U.S. and other wheat-growing countries; the oil crunch that results in higher freight charges. Pinca says they used to pay US$ 30MT; now, it is USD 60-65.

He adds that the incoming wheat shipments would be more expensive as it takes about three months after buying before delivery. Last year, they were paying USD 330 MT, now, $450MT, and incoming price will be over USD 500. “We have to buy no matter what the cost” as plants needs to run, workers need to be paid, and panaderos need their flour.

In terms of easing the price burden on consumer, Pinca notes that PAFMIL’s increase “is not commensurate with the price ” and that they do absorb some of the price increase, gradually.

Rising prices are also due to the higher cost of baking ingredients (sugar, yeast, shortening, vegetable oil) and fuel or LPG, Pinca adds.

Mauleon says that some community bakes have increased their prices; many others have reduced the weight of the pandesal dough, from 35 grams to 25 grams.

Koa notes that they did not decrease the weight of their bread products, as they consider themselves as setting the standards for the baking industry. He says that big bakers are here for the long-term, so they will try to absorb what they could, and try to survive the day, as there will be better days. And with prices rising every two weeks, and every month, they need to plan accordingly.

Koa adds that there are no prices increases for Pinoy Tasty and Pinoy regular pandesal—the only two bread products that DTI sets price control. In other words, all other bread products are subject to price increases.

To community bakers, Koa reminds that they should not compete on price alone. One can compete with baking schedule, service delivery, pleasant taste, softness, or offering breads hot. In other words, there are many other ways to market the product, other than price.

Consumer preference

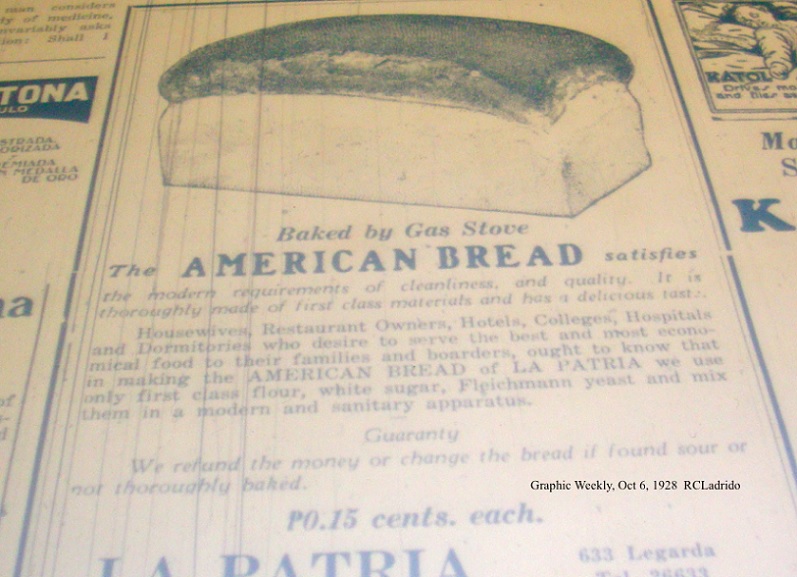

Pinca explains that the type of flour they buy is suited for the type of breads that customers like. In general. Filipinos prefer their bread to be soft, white, spongy, and with a shelf life of 3-5 days.

PAFMIL buys wheat such as U.S. dark northern spring with 14 percent protein or soft wheat with 10.5 percent protein for “tasty,” or sliced white bread that rises to 4-6 inches. Customers prefer bread made with this type of flour. Anything cheaper, people will complain.

Government help

Pinca exhorts the government to aid the industry, especially in reducing tariff on imported sugar, yeast, shortening, and vegetable oil, for example. Koa adds that having a regulatory environment conducive to long-term business is already happening. He says that it would be fantastic if they would be allowed to import their own sugar. And of course, they can be audited.

Mauleon notes that small bakers need help the most, from everyone. As part of their cost cutting, they are interested in using coco flour, or other vegetable crops (squash, malunggay, sweet potato) as add-ons to wheat flour.

Both Pinca and Koa state that while it is feasible, the maximum use for non-wheat flour should only be 10 percent. Using more than that would affect negatively the end product.

Wheat contains gluten, a substance containing proteins that gives bread its texture. Its elastic quality enables the dough to expand and rise. Pinca adds that first and foremost, extensive research needs to be done in using non-wheat flour.

Questions remain: How small will the pandesal shrink? Will Filipinos ever stop eating bread?