By JESSICA HERMOSA and JOHANNA SISANTE

WHILE ORDINARY Filipinos face the threat of food shortages caused by dwindling agricultural land, sugar barons in Congress are preoccupied turning their vast haciendas and other lands into plantations to produce and process biofuels.

WHILE ORDINARY Filipinos face the threat of food shortages caused by dwindling agricultural land, sugar barons in Congress are preoccupied turning their vast haciendas and other lands into plantations to produce and process biofuels.

One of those engaged in this move is presidential brother-in-law Ignacio “Iggy” Arroyo who hurdled last month most of the government requirements needed to convert his family’s 157-hectare Hacienda Bacan in Isabela, Negros Occidental into agro-industrial uses, mainly for the production of ethanol.

If the conversion pushes through, farmers charge that Arroyo will succeed in evading the Comprehensive Agrarian Reform Program, which covers rice, corn and sugar lands. It will nullify the claims of 67 farmer-beneficiaries who have been waiting for more than a decade for the Department of Agrarian Reform to award them Hacienda Bacan. Local DAR officials fear the Hacienda Bacan farmers will generate a big storm of protests.

The impending conversion of Hacienda Bacan not only contradicts supposed policy statements by President Gloria Macapagal Arroyo last week that she favored a moratorium on land conversions to preserve the country’s agricultural economy. It also shows how the country’s lawmakers—including a member of the President’s own family—are making a windfall from crafting laws designed to promote their own business interests.

Representative Arroyo declined to be interviewed for this report. His office said the land use conversion issue “doesn’t have any relevance” to the Biofuels Act.

Arroyo’s office also said the congressman, currently the chair of the House Committee on Natural Resources, is committed to “environmental protection” and has even begun working on a climate change bill after attending the climate change summit in Bali, Indonesia last December.

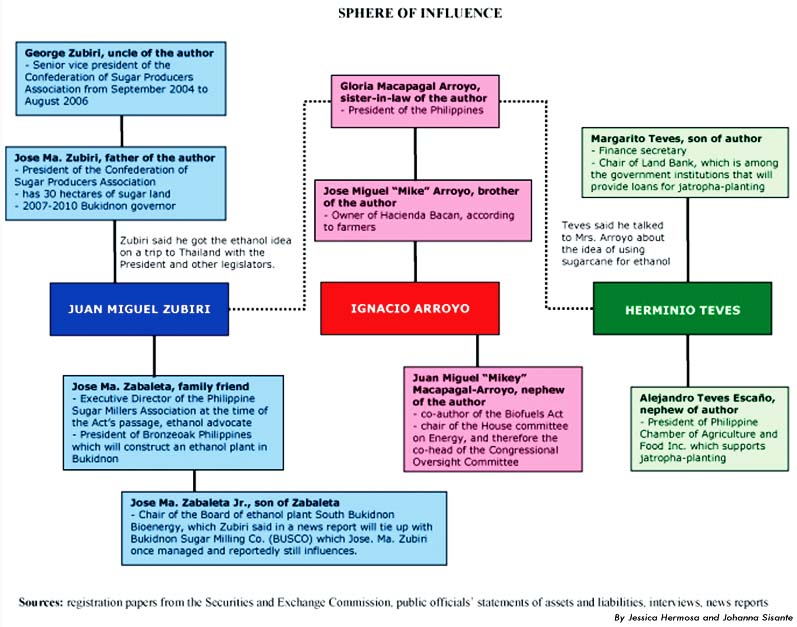

In the 13th Congress, Arroyo co-authored Republic Act 9367, also known as the Biofuels Act of 2006, along with then Negros Oriental representative Herminio Teves and Bukidnon representative now senator Juan Miguel Zubiri. They and eight other co-authors in the House and Senate and their families own agricultural lands that can or will provide feedstock for biofuel production.

Biofuels are liquid fuel produced by mixing fossil fuel with oil derived from biomass like sugar, coconut and jatropha. Although there have been studies questioning their overall environmental and economic impact, biofuels are expected to help countries attain energy and economic independence.

Teves, whose term in Congress ended last year, is already planting jatropha for biodiesel on 10,000 hectares of land in Negros Oriental and has even constructed a jatropha plant that will be operational by 2009.

Meanwhile, Zuburi’s father, former Bukidnon congressman now governor Jose Zubiri, has been the president of the Confederation of Sugar Producers Association since Sept. 1, 2006. The elder Zubiri was also once executive vice president of the Bukidnon Sugar Milling Co. which, Senator Zubiri said in a May 2006 news report, will tie up with the Bronzeoak Philippines to build an ethanol plant in Bukidnon. Senator Zubiri himself still owns at least eight hectares of sugar land in Maramag, Bukidnon.

Mike Arroyo owns Hacienda Bacan

When he was first elected to the House of Representatives, Arroyo filed the Fuel Ethanol Act of 2004 that was consolidated along with other bills to become the Biofuels Act. He is also the chairperson of Rivulet Agro Industrial Corp., which owns Hacienda Bacan. Arroyo, however, lists neither Rivulet nor Hacienda Bacan in his 2004 to 2006 statements of assets of liabilities.

The Arroyos own about 500 hectares of land in Negros Occidental. These include Haciendas Bacan, Grande, Fallacon, and Manolita, according to a DAR report. Bacan and Grande, in particular, are sugar plantations whose ownership has been hotly contested by various farmers’ groups.

Documents show Hacienda Bacan, which has belonged to the Arroyo family for decades, as being registered to Rivulet now chaired by Representative Arroyo. Task Force Mapalad, a nationwide alliance of about 25,000 farmers seeking land reform, said, however, President Gloria Macapagal-Arroyo’s husband, Jose Miguel “Mike” Arroyo, actually owns Hacienda Bacan.

“Alam naman natin na kay Gloria Macapagal Arroyo yung lupa (We know that the land is owned by Gloria Macapagal Arroyo),” said Ricky Celis, one of the 67 farmers claiming the land under CARP. “Talagang ayaw nilang bitiwan ‘to (They certainly won’t let go of the land).”

Mortgaged several times, Hacienda Bacan ran up millions of pesos in unpaid taxes to the municipal government and became a delinquent property that was auctioned off in April 1994 for P176.7 million. A certification of sale of the property issued by the office of the Isabela treasurer states it was sold to Jose Miguel Arroyo married to Gloria M. Arroyo. The First Gentleman’s ownership of the property, however, was not annotated at the back of the land title.

Amid calls to put the hacienda under the agrarian reform program when Gloria Arroyo became president in 2001, Ignacio Arroyo that same year offered the property under the voluntary offer to sell scheme of CARP to get a higher valuation.

Road to land conversion

The path toward converting the Arroyo sugar plantation began in October 2005 when the Isabela municipal council reclassified Hacienda Bacan from agricultural to agro-industrial land under a six-year comprehensive land use plan it approved through a resolution.

The land use plan, which spans from 2005 to 2010, was upheld by the provincial council in December that year.

Despite Hacienda Bacan’s reclassification, DAR provincial officer Teresita Depeñoso said Arroyo still has to apply for land use conversion with the DAR before he can put up an ethanol plant. Representative Arroyo has lost no time in doing so.

On Feb. 14, 2007, just a month after President Arroyo signed the Biofuels Act into law, Rivulet sent DAR-Negros Occidental advance copies of the application for conversion of Hacienda Bacan into industrial land.

In January this year, it installed eight billboards in Isabela town notifying the public of its intention to apply for land conversion with the DAR.

The DAR office in Isabela posted last March 3 a notice of Rivulet’s land use conversion application and issued just two weeks ago a certification of the company’s application.

The last step for Representative Arroyo is to now file these and other documents with the DAR Central Office, in particular the Center for Land Use Policy, Planning, and Implementation, to get his application processed.

DAR municipal agrarian reform officer Jose Defiño said formal protests, if any are filed, may stall approval of Rivulet’s application. “Siguradong marami ang mag- protest, mga members ng Task Force Mapalad (Many are expected to protest, especially Task Force Mapalad members),” he said.

Reclassifying and converting Hacienda Bacan to agro-industrial land will exempt it from CARP distribution because R.A. 6657 or the Comprehensive Agrarian Reform Law only provides for the distribution of agricultural land not classified as mineral, forest, residential, commercial or industrial land to farmers.

The 20-year-old CARP will expire on June 10 this year. Task Force Mapalad and the Catholic prelates are among the groups seeking an extension of the program.

Agrarian reform lawyer and former DAR Undersecretary Gil de los Reyes said that while the law allows the Arroyos to change their land use to agro-industrial for an ethanol plant, only the area occupied by the plant should be reclassified.

“No factory exists that will occupy the entire 300 hectares. At the most, what will you have (are) 10 (to) 20 hectares that will be converted from agricultural to non- agricultural,” he said.

If it pushes through, the ethanol plant will bring a windfall of benefits for the Arroyos. A 100,000 liter-capacity ethanol plant can make at least P3.2 million if ethanol sells at a profitable benchmark of P32 to P35 a liter based on estimates of the Sugar Regulatory Administration.

Even without an ethanol plant, Arroyo stands to gain more than P10 million annually if sugarcane planted in Hacienda Bacan is sold for ethanol production. The SRA estimates that sugar landowners can expect P65,000 annually for every hectare.

Ex-Rep. Teves into jatropha

The huge profits to be reaped from biofuels are an incentive for landowners like former congressman and Biofuels Act co-author Teves who has been growing jatropha trees on 10,000 hectares of leased hillsides in Tamlang Valley, a 24,000-hectare area straddling the municipalities of Valencia, Siaton, and Sta. Catalina in Negros Oriental, since last year. His biodiesel plant is set to start operations in 2009.

Jatropha seeds contain oil that may be processed into biodiesel.

“I leased a denuded area, mostly hills that cannot be plowed by tractor or even by carabao but can still be planted by jatropha,” the 89-year-old Teves said in an interview, leaning casually on his high-backed swivel chair.

Despite having ended his term as Negros Oriental third district representative in May 2007, he still occupies Room S-119 of the House Representatives, now the office of his nephew, Rep. Henry Pryde Teves.

Jatropha production gradually increases, said Teves who explained that 2,000 trees per hectare can be planted one year and 4,000 the next. He said jatropha production has opened up jobs for many residents of Tamlang Valley, adding that he offers profit-sharing to employees.

He expects to harvest 10,000 kilos of seeds per hectare after four years. About 3.5 kilos of seeds can produce a liter of oil which, he said, is “similar to bunker oil.”

However, agriculture experts from the University of the Philippines-Los Baños have found in a January 2007 study that jatropha only becomes a practical biodiesel feedstock if seeds yield at least 34 percent oil content.

The local variety, however, yields less than the practical standard. “Only 28 to 32 percent oil is said to be extractable,” the experts said.

This does not deter Teves from pursuing the biodiesel business. Now that his jatropha project is underway, he said he is “in no hurry” to sell the seeds as a lot of local and foreign investors are interested in buying them.

R.A. 9367 has no provision mandating local biofuel producers to supply the local market first before exporting their products. This means biofuel producers can choose to supply their product to higher-paying foreigners.

In fact, Teves plans to sell to the more lucrative foreign market. “The PNOC (Philippine National Oil Co.) and the oil companies here want to already sign an agreement with me. But I’m not in a hurry because I know there are foreign companies willing to buy,” he said.

He added that China and Japan are “very, very interested” to buy jatropha to produce biodiesel.

Minutes of the bicameral conference committee that fashioned the final version of the Biofuels Act reveal that Teves was apparently eyeing the foreign market even before the law was passed. In one of the rare moments that he spoke before the committee, he asked whether producers could sell abroad if local companies can’t keep up with world prices.

“So it’s not mandatory that a producer will have to sell to the local (market) if the price abroad will be higher?” he asked, to which then Senate Energy Committee Chair Aquilino Pimentel replied that there was no such provision in the proposed law.

Teves’ statement of assets and liabilities show that he acquired his first agricultural land in Sibulan, Negros Oriental in 1950, and later became the managing director of Tolong Sugar Milling in Sta. Catalina, Negros Oriental.

Today, his company, Herminio Teves and Co., which will finance his new jatropha processing plant, manages his sugar lands alongside rice and corn farms, piggeries, and subdivisions, mostly located in Tayawan, Sta. Catalina, and Bayawan. As of Dec. 31, 2006, while the then biofuels bill he co-authored was awaiting the President’s approval, his sugar lands were collectively worth P11 million.